Adoption and the Welfare State: Reply to Critics

My “Infant Adoption is Now Tragically Rare” provoked two response essays: one by Steven Salop, the other by Elizabeth Kirk and Ryan Hanlon. Here are my replies. Respondents are in blockquotes; I’m not.

Reply to Steven Salop

As an adoptive parent myself, I know that adoption is a wonderful experience. It is a great way to have a family and it gives you a deeper and broader perspective on parenthood. I am certainly in favor of supporting adoption. But I think that Bryan’s post left out some important points. And these points lead to a “rational counterargument” to his policy proposal and suggest possible alternative policies to protect the babies of low-income single mothers.

First, IVF has led to a substantial reduction in demand for adoption. There are almost 100,000 IVF babies born per year. By comparison, the number of adoptions in the US peaked at about 175,000 in 1970 and this figure may have included adoptions by relatives. This means the current demand may be fairly low, relative to the number of births by unmarried women. In 2023, there were about 1.4 million births by unmarried mothers. The number of births simply by teenagers was about 141,000 in 2023 and about 90% of these were unmarried teenagers.

This is definitely a major factor that I overlooked. But there still seems to be a severe shortage of healthy infants to adopt.

Second, many white families are unwilling to adopt Black or Hispanic children. This leads to low demand for these infants.

Plausible qualitatively, but I struggle to find any clear evidence that there is a full-blown surplus of healthy black or Hispanic infants. And if there were a surplus, my default would be to blame gatekeepers’ resistance to interracial adoption.

Third, new mothers love their babies and indeed are programmed by hormones to love them… It is not clear how many more will place children for adoption at birth in response to a reduction in child support by the government. After all, even with the welfare payments, the single mothers in Bryan’s “target group” are still poor and struggling.

I agree that single moms on welfare are very poor by U.S. standards. But being a single mom with an infant is clearly much easier with welfare than without, so why not presume a large effect?

If welfare is abolished, perhaps these more substantially impoverished mothers will eventually give up and try to find adoptive parents for their beloved children. However, the demand for toddlers and school age children is still lower, leading to the children languishing in foster care after becoming “legally available” for adoption.

Once you actually get to know your baby, your willingness to hand him over to foster care is probably very low. Even if that weren’t so, conformity pressure would soon shift norms in functional ways: Other single moms are putting their kids up for adoption, so you should do so, too.

Finally, it should also be recognized that while the economic circumstances of adopted children may improve, growing up adopted is a challenge for many adoptees. Feelings of loss and abandonment or simply not fitting in are common and often are not transitory. Those intense feelings are what leads many to search for their birth parents when they become teenagers or adults, as this story illustrates.

True, but deeply misleading. Shared family environment has approximately zero effect on overall adult happiness. So rather than thinking that adoption leads to lasting unhappiness, we should think that adoptees who are genetically prone to be unhappy often latch onto “feelings of loss or abandonment” as the thing they’re unhappy about. But if they were raised by their birth parents, they would have found plenty of other reasons to be unhappy.

This is certainly not a reason to reject adoption. Instead, it is a reason why adoptees also need support. In this regard, Bryan’s unvarnished claim that adoption is “fantastic for the baby” is somewhat more complex.

Not really. Being raised in a financially secure family really is, on average, much better than the alternative.

For all these reasons, if Bryan’s proposal to “drastically curtail or abolish” welfare payments for the children born to these single mothers were adopted, only a fraction would be adopted -- perhaps only a small fraction. And those children who were not adopted would be even worse off than they are today. This is a rational counterargument that Bryan failed to ventilate. Nor did Bryan consider alternatives.

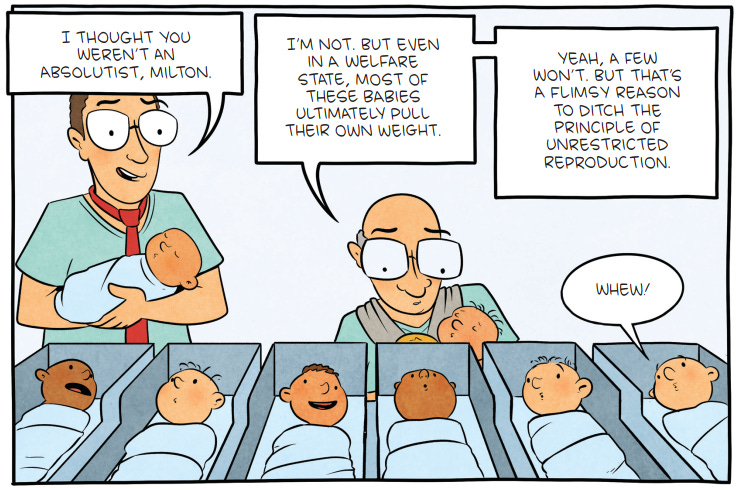

Suppose taxpayers are subsidizing air pollution. “Cutting the subsidies wouldn’t have a large effect on pollution, and the people getting subsidies are poor” is a good argument that the subsidies aren’t awful. But it hardly shows that subsidizing air pollution is actually a good idea. I say the same logic is at play here. As long as middle-class families are eager to adopt, why should government subsidize non-adoption?

Before embracing Bryan’s proposed policy, the cost/benefit tradeoff needs to be analyzed and alternative policies need to be considered. Perhaps the most obvious alternative would be policies to encourage and support women facing unwanted pregnancies to voluntarily choose adoption over abortion.

Fair enough.

One study found that among women denied access to abortion, only about 10% chose adoption, so simply prohibiting abortion is not the best route to supporting expanded adoption.

Probably true.

Adoptions also can be increased by subsidies and positive incentives rather than negative ones.

Definitely true.

As for the babies themselves, increasing support (not just child support and other welfare payments but also other interventions) would be a less draconian way to improve the outcomes for non-adopted children.

Yes, but with all the standard drawbacks and objections.

Providing easy access to birth control also would be important for these children since a poor single mother might be able to successfully care for one child but not three or four.

Honestly, how much easier can access to birth control possibly be? And wouldn’t it be better if she offered the extra children for adoption than if they never existed?

Reply to Elizabeth Kirk and Ryan Hanlon

Adoption is rare, especially when compared to single parenting or abortion. For every child placed for adoption, approximately 70 other women choose to rear the child as a single parent, and 50 other women choose to terminate the pregnancy. Adoption has been described as the “non-option.” The numbers are so startling that we wrote an article explaining why we think it’s so rare. We label this the “adoption paradox”: adoption enjoys broad cultural support, yet it’s rarely chosen in the moment of decision. That article was based on research combining an extensive survey of birth mothers with a review of social-science literature. Our findings point to misunderstandings that depress consideration of adoption: confusion between private adoption and foster care, uncertainty about open adoption, and lack of awareness that expectant parents can choose the adoptive family and receive services at no cost. This is not a problem of “bad incentives” so much as bad information at the exact time when clarity is most needed.

How much of the problem is bad information, and how much is good information about a bad system? I’m not sure, but I strongly suspect that adoption would be much more common if it were treated as an ordinary contract between birth mother and adopting parents rather than sticking with the byzantine system we have today.

That insight matters for policy, and this is where we part ways with Caplan. He proposes we “drastically curtail or abolish the welfare state” so that more women would place infants for adoption. Against the backdrop of our research, it’s not clear that this would have such an effect. Perhaps it would increase single parenting, render more children vulnerable to the child welfare system, or drive up the abortion rate.

I can see why it might drive up the abortion rate. But why on Earth would cutting welfare increase single parenting?

In any case, setting aside efficacy or political impossibility, we think the proposal aims at the wrong target. We should not design or dismantle welfare programs hoping they produce more adoptions. Adoption is not society’s consolation prize for threadbare safety nets; it is a child-centered option that ought to be presented clearly, fairly, and without pressure.

I say that the clear, fair view is that it is normally much better for a child to be raised by a financially secure family than a poor single mother. Do you really disagree? If not, why isn’t the fact that the welfare state discourages this result a mark against it?

On that score, the same research highlights a striking trend: compared with the mid-20th-century “baby-scoop” era, today’s birth mothers who placed for adoption overwhelmingly report they made a free, informed choice—fewer than 1 in 10 say otherwise—and their long-term satisfaction is closely tied to that autonomy. That’s the direction in which we should keep moving.

This is the standard normative framework that I’m criticizing. Why focus almost exclusively on the satisfaction of the birth mother, rather than the often conflicting interests of the child, potential adoptive parents, and taxpayers?

Ending the welfare state has enough positives without considering its effect on single mothers/adoption/abortion/etc.

Paraphrasing Bryan from both his graphic novels, when you have a trillion dollar idea, the thousand dollar effects don't really matter.

The most convenient, reliable forms of birth control (IUD and vaginal ring) both require prescriptions so yes birth control could be much more accessible.