A Better Path Forward for Infant Adoption

A guest post by Elizabeth Kirk and Ryan Hanlon

After I posted my “Infant Adoption is Now Tragically Rare,” Elizabeth Kirk of Catholic University sent me her “Informing Choice: The Role of Adoption in Women’s Pregnancy Decision-Making,” co-authored with her colleague Ryan Hanlon. I then invited them to write a critique of my essay based on their article, and they kindly accepted. Here’s their essay. Enjoy!

Bryan Caplan is right about one big thing: the collapse of intercountry adoption is tragic, given that there remain hundreds of thousands of children in need of families – and there are plenty of families open to adopting them. The demographics of who is being placed for intercountry adoption have changed in recent years (trending older, most have medically complex special needs) as infants are no longer available, but as Caplan’s post made clear, the big change has been the 95+% decline in the overall number of adoptions. That is not a rounding error—it is a policy failure that has left children waiting and families in limbo. The State Department’s own FY2024 report chronicles program slowdowns and country closures (including China’s 2024 announcement), while advocates have documented how “safeguards” morphed into roadblocks. We can agree, as Caplan does, that Washington officials should work cooperatively with partner nations to reopen ethical pathways rather than layering on bureaucratic hurdles that shut them down.

Caplan is also correct that domestic infant adoption is rare, although its trajectory is much more nuanced than international adoption. The United States does not publish an official annual count of private domestic infant adoptions (a longstanding data gap), but the best available proxies suggest relative stability in recent years. National Council For Adoption (NCFA)’s latest round-up estimates about 25,000 private domestic adoptions per year.

Adoption is rare, especially when compared to single parenting or abortion. For every child placed for adoption, approximately 70 other women choose to rear the child as a single parent, and 50 other women choose to terminate the pregnancy. Adoption has been described as the “non-option.” The numbers are so startling that we wrote an article explaining why we think it’s so rare. We label this the “adoption paradox”: adoption enjoys broad cultural support, yet it’s rarely chosen in the moment of decision. That article was based on research combining an extensive survey of birth mothers with a review of social-science literature. Our findings point to misunderstandings that depress consideration of adoption: confusion between private adoption and foster care, uncertainty about open adoption, and lack of awareness that expectant parents can choose the adoptive family and receive services at no cost. This is not a problem of “bad incentives” so much as bad information at the exact time when clarity is most needed.

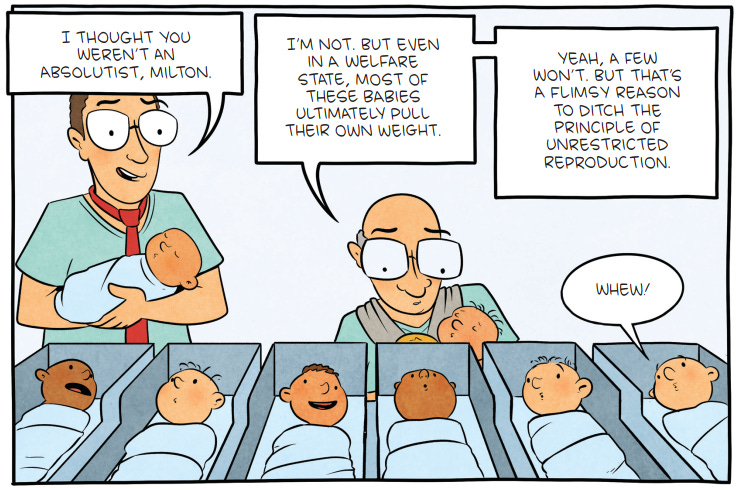

That insight matters for policy, and this is where we part ways with Caplan. He proposes we “drastically curtail or abolish the welfare state” so that more women would place infants for adoption. Against the backdrop of our research, it’s not clear that this would have such an effect. Perhaps it would increase single parenting, render more children vulnerable to the child welfare system, or drive up the abortion rate. In any case, setting aside efficacy or political impossibility, we think the proposal aims at the wrong target. We should not design or dismantle welfare programs hoping they produce more adoptions. Adoption is not society’s consolation prize for threadbare safety nets; it is a child-centered option that ought to be presented clearly, fairly, and without pressure. The better metric is whether expectant parents can make an informed, non-coerced decision serving their best interests and that of their child. On that score, the same research highlights a striking trend: compared with the mid-20th-century “baby-scoop” era, today’s birth mothers who placed for adoption overwhelmingly report they made a free, informed choice—fewer than 1 in 10 say otherwise—and their long-term satisfaction is closely tied to that autonomy. That’s the direction in which we should keep moving.

So, what would responsible, adoption-positive reform look like?

1) Make adoption intelligible at the point of care. Most states either provide scant information about adoption in clinical settings or reduce it to a brochure list of agencies. That’s a missed opportunity. Health systems and state policymakers should ensure that early, nondirective counseling includes the basics: (a) private domestic adoption is not foster care; (b) open adoption is common; (c) expectant parents can select the family; and (d) legal, medical, and counseling services for expectant parents are provided at no cost. This is not about steering outcomes; it’s about equipping adults to decide. (Health care workers interested in this can access a free training and get free continuing education credits.)

2) Educate the public about the option of adoption. Given what we learned about the lack of knowledge about adoption and the misconceptions about its practice, it won’t do much good if we leave education to the moment of crisis. To increase public awareness about the option of adoption, we recommend that school health education curricula include clear and accurate information about contemporary adoption practices.

3) Make space for voluntary relinquishment within child welfare—carefully. There is a delicate but important opportunity to improve outcomes for children who are already within the dependency system. In some states, a parent may voluntarily relinquish parental rights during an open case, with counsel, if an agency is willing to accept the relinquishment and the court finds it appropriate. This limits the child’s time in foster care and provides her with a stable adoptive home. When families have clear information, competent legal representation, and the option of an identified adoptive placement (including relatives), voluntary relinquishment can shorten uncertainty for the child and respect a parent’s judgment about what is best. The key is informed choice, not pressure. Framed correctly, this is the opposite of coercion: it treats parents as decision-makers with rights, not as bystanders to “the system.” In cases where that option is chosen, it would also achieve Caplan’s goal of reducing taxpayer burden.

4) Separate adoption policy from proxy battles. Both sides in debates about abortion, welfare, and family law often conscript adoption as a talking point. That rarely helps pregnant women or their children. The aim should be a landscape where all parents facing an unplanned pregnancy or difficult circumstances receive accurate, timely information about adoption; where adoption professionals provide trauma-informed care and post-placement support; and where adoptive families and birth families can form durable, open relationships centered on the adoptee’s well-being. That is good for parents and children, and consistent with what the best research tells us about satisfaction and outcomes.

Finally, a word about tone. Caplan’s line, “often sad for the birth mothers, but fantastic for the baby and whoever adopts the baby,” captures real, mixed emotions but risks flattening or dismissing the experience of women who place. Many report grief and happiness, sorrow and pride in a thoughtful decision; many sustain relationships with their child and the adoptive family through open adoption. If we want more women to consider adoption, we shouldn’t ignore their experiences. Instead, we can provide honest depictions of what modern adoption is: a demanding, ethical practice that centers on a child and honors the adults who love that child. That is a future worth working toward.

Adopting foreign babies seems like a great way to get more immigration.

“Adoption is not society’s consolation prize for threadbare safety nets; it is a child-centered option that ought to be presented clearly, fairly, and without pressure. The better metric is whether expectant parents can make an informed, non-coerced decision serving their best interests and that of their child.”

Incentives are NOT coercion. The welfare system incentivizes women to keep unwanted pregnancies and get married to the state who will reward the mother’s choice with a monthly payment for each child (this varies by state and doesn’t include other welfare benefits).

Why not have the adopting parents pay a fee to the birth mother—what could go wrong with that kind of incentive?!

PS—What supporters of welfare and its victims don’t seem to understand is that welfare is the cause of the poverty inertia. If the state keeps paying women to have babies they will.