Reflections on Peru and Bolivia

I’m back from all my travels! Unfortunately all Caplan guys got fairly sick in South America (respiratory not digestive), but we’re finally almost back to 100%. Special thanks to honorary Tío Fabio Rojas for teaching my three sons how to be cool guys. My main thoughts on the journey:

Lima is an economic powerhouse, but a mediocre tourist destination. We enjoyed the pre-Incan archaeological sites and the Museo Larco archaeological museum, including its rather tame erotica gallery. But we never found Peruvian food as good as northern Virginia’s Wild Chicken or Superchicken. We encountered the most frightful traffic jam of my life at midnight near the airport, even though no one was injured and the delay was only 40 minutes. Lima’s highlight was ringing in 2026 on our apartment rooftop. The city looked like it was under attack by a flamboyant superpower. Best fireworks show of my life!

The logistics of visiting Machu Picchu are agonizing. The tickets are grossly underpriced, hence severely rationed. The website by default only lets you book 2026 tickets starting in 2026. (Exception: You can book January 2026 tickets starting in mid-November, not December 1 as I somehow came to believe). The magic bus and train ticket from Cusco to Pueblo Machu Picchu is not underpriced, but the website bizarrely changes the ticket date to tomorrow when you change the number of passengers from the default of 1, so I accidentally wasted $400 on mis-scheduled train tickets for weeks before our trip. The final bus from Pueblo Machu Picchu to the site also has long lines, but mostly because they insist on matching the names on the $6 tickets to passports. For thousands of passengers every day!

Peru in general, and Machu Picchu in particular, had the most fascist “papers please” system I’ve ever encountered. Worse than India! The initial logic, presumably: Due to absurd fairness norms, the Peruvian government grossly underprices Machu Picchu tickets. This in turn leads to resale paranoia, hence multiple checks to make sure that the name on your Machu Picchu ticket matches the name on your passport. But this resale paranoia puts Peru on a slippery slope where they repeatedly check every ticket against your passport, even though most of the tickets are not underpriced and hence little danger of resale. So in order to preserve this atavistic fairness regime, the Peruvian government dumps a dozen bitter buckets of ice-cold bureaucratic water on every visitor to its most amazing archaeological site.

Machu Picchu is so jaw-dropping that it would have been worth three dozen bitter buckets of ice-cold bureaucratic water! In the end, we were able to get tickets for two suboptimal tours rather than the one optimal tour, but both were peak experiences. The geography is alien, the architecture superhuman, and the combination — all confirmation bias aside — sublime. My chief regret: Even with strong altitude sickness pills and a relatively low altitude for the Andes, we lacked the endurance for the so-called two-hour hike to the summit of Huayna Picchu.

If you’re a true friend or a paid subscriber, I am happy to walk you through the correct step-by-step process for a Machu Picchu visit. Just email me and I will happily spare you hours of pain. (In a few years, the system may change or my memory will fade, but for now, I’m the Machu Picchu visit master).

The smaller archaeological sites in the greater Cusco region are also awesome, especially Ollantaytambo and Sacsayhuaman. Awesome enough to outweigh their gross mismanagement by the Peruvian government! Seriously, you can buy a 1-sol facemask from a street vendor with a QR code, but site tickets must be purchased in Peruvian cash. For a group of six, that’s a lot of cash — and the Peruvian ATM machines are finicky, have low maximum withdrawals, and charge large fees per withdrawal.

I quite liked Cusco itself, but my younger son was traumatized by the poverty of the shantytowns. Since he skipped my India trip, he kept asking, “Was India this bad?” And since I’ve seen India, I kept answering, “Far worse!” In my son’s mind, a majority of the people in Cusco lived in shanties, but the true share was more like 20%.

Expedia kept hiding nonstop tickets from Cusco to La Paz, but the flight does exist and is totally worth it compared to the defaults of connecting in Lima or freakin’ Bogota. La Paz (and the adjacent city of El Alto) have insane altitude, but it was hard to disentangle the physical burden of altitude from the burden of the respiratory sickness we all caught in Peru. We all still managed to see the top geological sites — Valle de la Luna and Valle de las Ánimas — but my younger son never found the energy to ride the cable cars.

The cable cars of La Paz are a modernist and YIMBY marvel, a taste of Japan in the high Andes. Austrian-built, Mi Teleférico is spotless, reliable, cheap, and apparently queue-free. Cable car is the perfect way to view a city — a plane is too high to see the details of daily life, and a car is too low. While I’m no fan of public transit, all Abundance bros should book their flights to La Paz today. Here’s the ChatGPT table of completion times and construction costs, which seems accurate when checked against other sources. The first cable car line took only 19 months to complete, at a cost of just $54 million. Cost-justified? Maybe. Amazing? Definitely. A roaring reproach to the state of California? Absolutely.

Based on low Uber rates and high grocery store prices, La Paz is markedly poorer than Cusco, never mind Lima. Transportation costs are plainly high, but I’d be amazed if tariffs and other trade barriers weren’t far larger factors. Seriously, if you could sell Kirkland olive oil and pistachios for half of what La Paz’s grocery stores charge, you could live well just by doing a round-trip flight to the U.S. once a month and paying for extra baggage.

As you may have heard, Bolivia’s socialists’ two decades of political domination finally ended in a humiliating electoral defeat in late 2025. Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS) dropped to 3% of the vote, with their longtime strongman Evo Morales barred from the election. This is arguably the greatest reversal of fortune in the history of modern democracy, so political scientists and political economists alike ought to be obsessing over “What the hell happened in Bolivia?!”

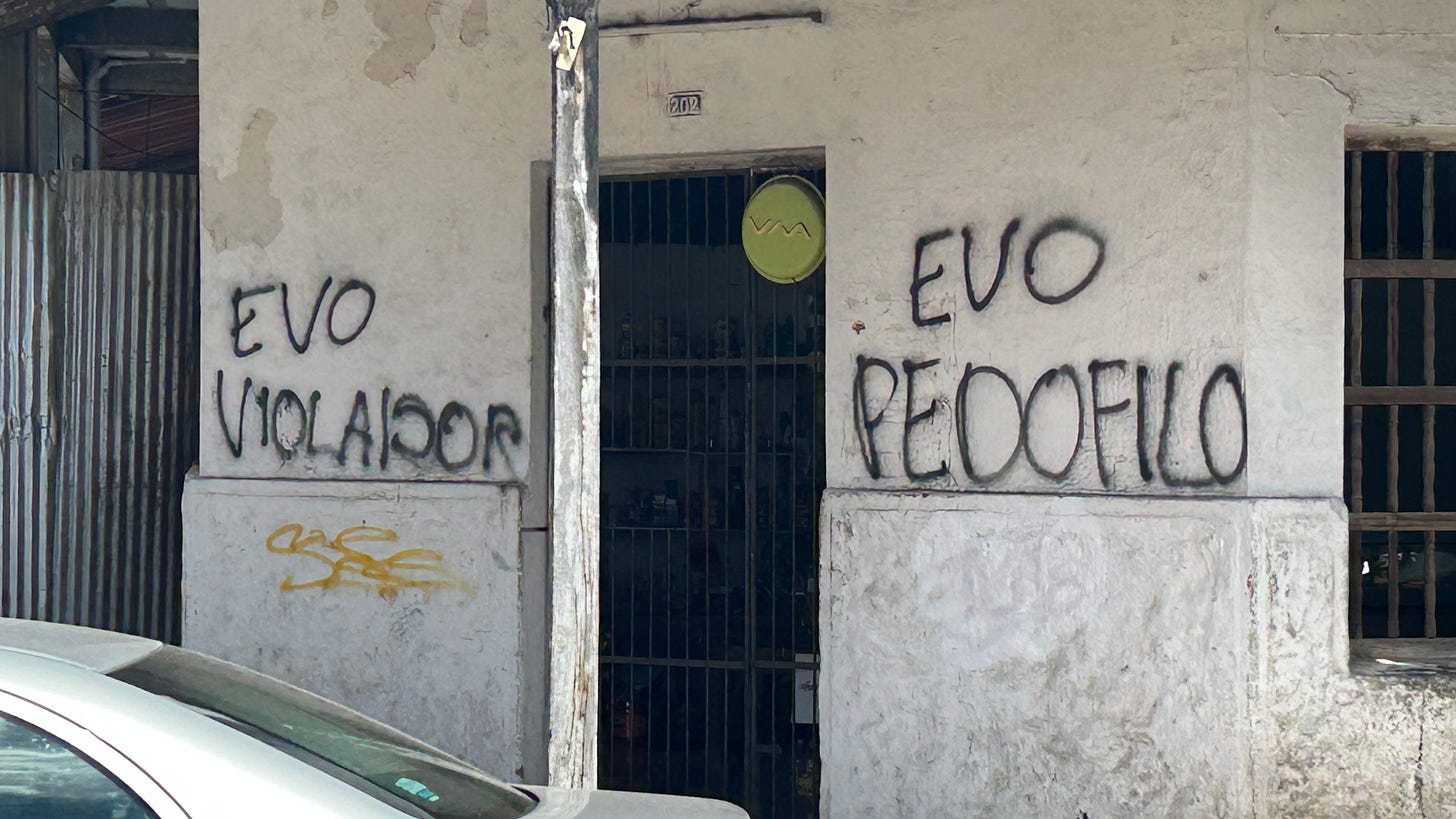

Even though he was forced out by his own party back in 2019, anti-Evo graffiti blankets the country, focusing on his alleged rapes and pedophilia rather than economic crises and international isolation. The new president’s speeches, looping in the airports, sounded good: His “Capitalism for all” is a truly Caplanian slogan. After a cable-car ride to the historic downtown, we saw teamsters protesting his fuel subsidy cuts. While we saw no clash with the cops, barricades prevented us from touring the colonial center of town.

After La Paz’s insane altitude, we flew to the rain forest of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, near sea level. Markedly richer than La Paz and probably Cusco, but the roads get bad once you’re 5-10 miles from the city center. Even so, four-star hotel rooms cost $25 a night. (Update: The $25 rate reflected a major discount Hotel Novotel SCZ granted the organizers).

Almost immediately on arrival, I spoke on “Don’t Be a Feminist” to the Ladies of Liberty Alliance Bolivia. I think that’s the first women’s group I’ve ever addressed, and it was top-notch. While I was open to the idea that Bolivian women received markedly more unfair treatment than First World women, I don’t think anyone in the audience advanced that view.

The Santa Cruz Economic and Political Forum in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, was a full-blown Caplan-Rojas Show. I spoke in English, Rojas in Spanish, all with high-quality simultaneous AI translation. Main surprise: My Bolivians are quite worried about population collapse, even though almost every source says that Bolivia has the highest fertility in South America.

The visit was organized by the local chapter of the Center for Public Policy Studies for Liberty (POPULI), with support from Río de Libertad. A fine and thoughtful group, whose members will hopefully push the new government in a Milei direction. Special thanks to director Wilboor Brun, spokesman Carlos Aranda, and the dashing young political historian Oscar Tomianovic, author of Ensayos sobre la crisis democrática. After visiting the cable cars of La Paz, Abundance bros should continue to Santa Cruz to meet POPULI team. I’m happy to handle introductions.

While we originally planned a side trip to Sucre, Potosí, and Uyuni, we didn’t want to find out how much a massive elevation gain would exacerbate our coughing and low energy. Furthermore, we kept hearing conflicting reports about teamster blockades (yes, the same teamsters who were protesting fuel subsidy cuts in La Paz) cutting off crucial roads. So alas, we came home early without experiencing these world-famous Bolivian gems.

Back in October, visa and vaccine requirements for Bolivia seemed so onerous that I almost cancelled the whole South America trip. But my friends at POPULI arranged an alternate entry plan where my sons and I would (a) get yellow fever vaccines near our place in Lima, and (b) hire visa consultants in Cusco to handle our entry. In the end, the new government dropped all visa requirements for U.S. citizens, and no one even checked our vaccine cards. Given current near-zero rates of yellow fever prevalence and death, the vaccine requirement is quite absurd. You can imagine that Bolivia’s government fears horribly negative publicity of even a single tourist fatality, but as my son Tristan points out, the vaccine requirement is itself horrible negative publicity, because it creates the false impression that Bolivia is teeming with yellow fever.

All of my experience with Bolivia’s visa situation strongly confirms the Lawson-Roychowdhury result, popularized by Alex Tabarrok, that visa requirements drastically reduce tourism. Unfortunately, Bolivian tourism is still in an awkward transitional state. Despite the official policy change, my friends urged me to have all of the documents (including the vaccine cards plus $640 in Peruvian soles!) in case local immigration officials hadn’t gotten the memo. Even today, it’s unclear if Bolivia actually dropped the yellow fever vaccine requirement, or simply failed to transfer verification responsibilities from consulates to local officials.

The lowest-hanging fruit of economic reform for both Peru and Bolivia is to privatize archaeological and geological and tourist sites. There is no reason Machu Picchu shouldn’t be running 24 hours a day, using money, not queuing and passports, to ration access. What Alex Epstein calls the “anti-impact standard” is hobbling tourism as well as energy. Seriously, all of the new revenue could easily pay for extra maintenance, more excavation, and yes, a full network of awesome cable cars. Thanks to the all the mountains, you could keep the famous views intact while ramping up convenience to the skies. ¡Adelante Perú y Bolivia!

![r/TransitDiagrams - [OC] Mi Teleférico (La Paz—El Alto Cable Car) r/TransitDiagrams - [OC] Mi Teleférico (La Paz—El Alto Cable Car)](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Tj31!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff9ff34b3-b926-445b-8147-6f6251d750b0_10200x5100.png)

Sounds like a wonderful trip. A couple of clarifications about Bolivia politics relevant to points 11 and 12. In 2019, Evo Morales ran for a 4th consecutive term as President of Bolivia. This act was controversial, as the constitution does not allow for more than two consecutive terms; in 2016 Morales lost a refedendum trying to amend the constitution to lift this restriction. Despite this prohibition, the Constitutional Court ruled in favour of letting Morales stand. Morales then proceeded to win the election, but the win was controversial, and after many protests and pressure from different entities he decided (or was forced to) stand down. However, he wasn't exactly forced out by his own party, and he remained popular with them.

The next year presidential elections were held again, and this time Luis Arce, a former minister under Morales and member of the same party, MAS, won comfortably. During the beginning of Arce's term, Arce and Morales were close, but grew apart. Morales was not allowed to stand in the 2025 election, and is being prosecuted for child abuse, which led to Morales publicly facing off against Arce. Morales' supporters, in protest, decided to cast invalid votes, which were far higher in 2025 (19%) than in 2020 (3%). There was also another leftwing candidate, initially close to Morales but who then became a rival, who got around 8%. Thus, counting the "extra" invalid votes (16% of the total votes, equivalent to around 20% of the valid votes) plus this second leftwing candidate, plus the government candidate (3%), we obtain that the true support of the Morales-adjacent left is around 33%. This number is terrible by their standards of the last 20 years, but a far cry from 3%. Also, I don't know where or what you ate, but Peruvian food is amazing.

A wonderful travelog. I live in Ecuador, just a few hours from the Peruvian border, and have considered visiting the sites you described, but there is a LOT to see even closer to home, and at 72 years young, traveling doesn't have the appeal it once had. But I really enjoyed your tips and descriptions.