The Toothpick Problem

Two days ago I posed the following hypothetical:

Suppose half of the sectors of the economy grow forever at 4%, while the rest completely stagnate. I’m strongly tempted to say that this economy’s growth rate equals 2% forever. Anyone tempted to disagree?

If so, why?

Answers in the comments spanned the entire range. Some said that the growth rate would asymptote to 4%. Phil:

The growth rate will increase over time to approach 4% asymptotically as the 4% sector grows relative to the 0% sector.

Tyler, in contrast, said that the growth rate would asymptote to 0%:

Eventually the growth rate converges to zero or near-zero…the growing sectors become quite small in gdp terms and their future gains cease to matter very much.

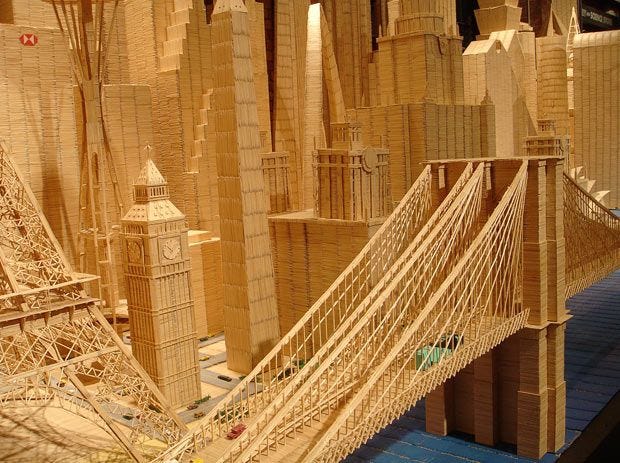

My claim: Both the 4% and the 0% answers are vulnerable to a reductio ad absurdum that I call the Toothpick Problem. Imagine an economy with a million goods. One of them is toothpicks.

Reductio ad absurdum for the 4%-ers:

Suppose toothpick production grows at 4% forever, and the rest of the economy stagnates. Doesn’t your position imply that “economic growth” asymptotes to 4% despite near-total stagnation?

Reductio ad absurdum for the 0%-ers:

Suppose toothpick production stagnates, but production of every other good grows at 4% forever. Doesn’t your position imply that “economic growth” asymptotes to 0% despite near-universal progress?

The absurdity of both extreme positions is what draws me so strongly to the 2% answer in my original hypothetical. Weighing output using initial shares isn’t perfect, but it’s reasonable relative to the alternatives.

P.S. The Toothpick Problem is also the heart of my response to Robin Hanson’s insistence that growth has to fall to zero:

Our finite universe simply cannot continue our exponential growth rates for a million years. For trillions of years thereafter, possibilities will be known and fixed,

and for each person rather limited.

He’s probably right for physical goods. But why couldn’t the quality of life in virtual reality grow at 4% for ever? Serious virtual reality wouldn’t be like toothpicks; it would be a vast array of virtual goods and experiences. And since these goods and experiences would be imaginary, there’s no reason they couldn’t grow forever. Laugh if you must: Imagination really is infinite!

The post appeared first on Econlib.

I'm extremely skeptical that this is a meaningful question. There are so many modeling choices in the division into sectors, and in what single value is measured for growth. It's simply not useful to project more than a few orders of magnitude without having to rethink your whole system.

If it _WERE_ sane to ask, then of course it converges to 4%, because after a few centuries, that sector (or product, for toothpicks) is the only relevant thing in the economy. This should show the absurdity of the question, not the incorrectness of the answer.

I don't understand...first you're asking us to split the economy in half, then we're only talking about toothpicks (or presumable any single other good)?

Also, Virtual Life isn't free, it costs energy. I understand the point that there's no limits to what a virtual economy might provide, but it's all rooted in physical goods somewhere along the line, no?