The Tragic Hysteria of Abortion

I actually have something original to say about the morality of abortion.

The radical pro-life position — “Abortion is as immoral as murdering a baby” — is easily refuted with a simple thought experiment. Namely: If you could either save one human baby from a fire, or a dozen human embryos, what are you morally obliged to do? Almost no one even claims they should choose the embryos over the baby — and virtually no one would in fact do so.

Why not? Because almost everyone recognizes that an embryo has far less moral worth than an actually-existing baby.

Yet on reflection, the radical pro-choice position — “Abortion is morally neutral” — is also easily refuted with a parallel thought experiment. Namely: If you could either save one human embryo from a fire, or just let it burn, what are you morally obliged to do? Again, only a small minority even claims they would shrug and walk away. Why not? Because a large majority recognizes that a fertilized egg has intermediate moral value. Abortion is not murder, but neither is it the same as removing a wart.

Another way to grasp the same point: The death of a child is objectively much worse than a miscarriage. But telling a couple that has experienced a miscarriage, “Sure, this is sad for you. But your embryo wasn’t sufficiently developed to have any independent moral value” isn’t merely rude. It is absurd. When a miscarriage occurs, a reasonable person recognizes the tragedy — not just for the parents, but for the fetus who will never be born.

My friend Richard Hanania is deeply dismissive of the pro-life position: “Somehow pro-lifers have convinced themselves there’s a non-religious basis to their beliefs.” But the aforementioned moral intuitions about the intermediate moral value of an embryo are hardly sectarian. I’m an atheist of the highest order, and the aforementioned moral intuitions make perfect sense to me.

What are the implications? To start, abortion is definitely morally justified in extreme scenarios. If a woman will die unless she gets an abortion, she should get an abortion, because the embryo matters far less than her actual human life. The same holds if a pregnant woman is so poor that one of her existing children will starve to death if she doesn’t get an abortion.

The same plausibly holds if having her baby would cause zero fatalities, but truly ruin the life of the pregnant woman. Preventing the lifelong immiseration of a being with great moral worth matters more than the destruction of a being of intermediate moral worth.

If this seems trivial, it’s not. Yes, “an embryo has intermediate moral worth” implies that abortion is morally justified in dire circumstances. But it also implies that abortion is not morally justified in merely unpleasant circumstances. Aborting to avoid years of moderate inconvenience is not justified. Neither is aborting to avoid brief misery.

Note: What morally matters is the actual severity of the consequences, not the perceived severity of the consequences. If you mistakenly believe that getting an abortion will not save your life, you should still get one. If you mistakenly believe that getting an abortion would save your life, you shouldn’t get one. The same goes for “a baby would ruin my life.” If you wrongly deny this, abortion remains right. If you wrongly affirm it, abortion remains wrong.

Crucial point: As usual for any morally important decision, there is a corresponding duty to calmly try to figure out the true state of the world. We’re all fallible, but that’s no excuse for epistemic negligence. The legal concept of “depraved indifference” elegantly captures this principle: If a man throws a grenade into a room without bothering to see if it’s occupied, he’s still guilty of murder if anyone dies. Why? Because he had a moral obligation to look in the room before he tossed the grenade inside.

Only a small minority of pregnancies have horrible physical consequences, and people who are contemplating an abortion rarely claim otherwise. But when contemplating an abortion, many if not most prospective parents predict horrible mental consequences for themselves. In the vernacular: “A baby would ruin my life.” If my argument so far is correct, the correct reaction to such claims is not to stonewall with: “Too bad” or “Trust women.” The correct reaction is to ask: “Is it really true that a baby would ruin your life?”

The strongest known evidence on this question is Diana Foster’s “Turnaway Study,” which uses what economists call a regression discontinuity design to estimate a long list of causal effects of abortion. Foster interviewed women in abortion clinics who were near the legal cutoff. Some turned out to be just below the cutoff — and normally ended up getting an abortion. Some turned out to be just above the cutoff — and normally ended up getting a baby.

I learned about Foster’s work twelve years ago, but only recently did I read her full book: The Turnaway Study: Ten Years, a Thousand Women, and the Consequences of Having ― or Being Denied ― an Abortion.* Foster walks readers through the study and the co-authored research that came out of it. The book is careful, thorough, wide-ranging, well-written, and creative. While Foster is obviously deeply pro-choice, her methods are sound and her presentation is transparent. The book’s most notable findings:

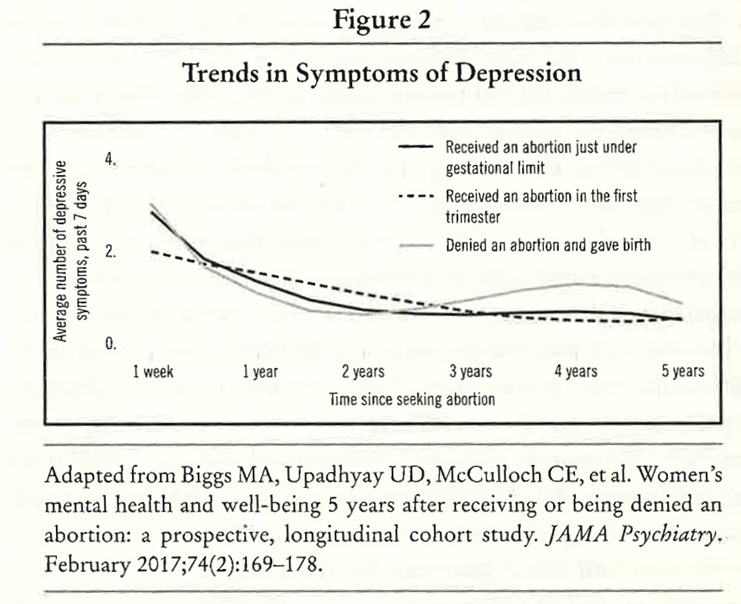

Women who managed to get abortions had almost exactly the same self-reported well-being as the turnaways: “Shortly after being denied an abortion, women had more symptoms of anxiety and stress and lower levels of self-esteem and life satisfaction than women who received an abortion. Over time, women’s mental health and well-being generally improved, so that by six months to one year, there were no differences between groups across outcomes. To the extent that abortion causes mental health harm, the harm comes from the denial of services, not the provision… Yet once the pregnancy was announced, the baby born, and the unknown fears and expectations realized or overcome, the trajectory of mental health symptoms seems to return to what it would have been if the woman had received an abortion.” To illustrate, here’s the key figure on depression from the book.

This co-authored article shows results for all of the Turnaway study’s measures of mental well-being. Effects are minimal across the board. For life satisfaction on a 1-5 scale (5 being highest), the initial results are 3.1 for women denied an abortion versus 3.3 for those who received one. After six months, even this tiny gain from abortion fades out.

In hindsight, virtually all women — 95% — who got an abortion say that it was the right decision for them. Foster repeats this result throughout the book. But to her great credit, she also reports parallel hindsight results for women who were denied an abortion: “How do women feel about having been denied an abortion? Initially, bad. But over time, most of the women who ended up carrying the unwanted pregnancy to term reconciled themselves to their new reality, especially after their babies were born. One week after abortion denial, 65% of participants reported still wishing they could have had the abortion; after the birth, only 12% of women reported that they still wished they could have the abortion. At the time of the child’s first birthday, 7% still wished they could have had an abortion. By five years, this went down to 4%.”

Foster and co-authors found moderately negative economic effects of abortion denial. Six months after seeking an abortion, 45% who got the abortion were living in poverty, versus 61% who didn’t. After five years, this 16 percentage-point gap shrank to about 5 percentage-points. There are similar results for credit scores. Women denied an abortion also had sharply more past-due debt, and a large percent (not percentage-point) rise in evictions, bankruptcies, and such.

How can subjective well-being barely change despite moderately negative economic effects? The obvious answer is that the direct emotional benefits of the baby balance out the indirect emotional costs of the baby’s economic burden. Which could mean that both gains and losses feel similarly small, similarly medium, or similarly large.

Why are Foster’s results important? In her mind, because she refutes the claim that abortion is really bad for women. While she does indeed refute this claim, she also refutes the claim that being denied an abortion is really bad for women. At minimum, then, she undermines both the pro-life and the pro-choice positions.

But on further thought, Foster undermines the pro-choice view more. Why? While many pro-life thinkers falsely claim that abortion is really bad for women, that is almost never their primary argument. Their primary argument, rather, is that abortion is really bad for the unborn — a truism that Foster barely considers.

In contrast, “Being denied an abortion is terrible for women” is one of the top pro-choice arguments. Maybe the very top such argument. Since Foster shows that this argument is false, pro-choice thinkers have to fall back on the deontological “My body, my choice.” Which is a shaky foundation at best, because (a) few pro-choice thinkers embrace the principle of bodily integrity for prostitution, narcotics, or pharmaceutical regulation, and (b) the unborn’s bodily integrity is also on the line.

As I explained at the outset, I think that the radical pro-life and radical pro-choice views are both wrong. Pro-life overrates the value of the unborn; pro-choice underrates it. Once you accept the reasonable view that the unborn have intermediate moral value, what do Foster’s results imply?

The lesson, for most purposes, is a blunt: Don’t get an abortion. If an unwanted pregnancy will really ruin your life, you should get one. If an unwanted pregnancy is a moderate, temporary burden, however, you shouldn’t. Foster strongly confirms that the latter scenario overwhelmingly dominates in the real world. Unless your situation is extremely bleak compared to those faced by other women who want to end their pregnancies, you should keep your baby.

How can we reconcile this with the widespread perception that an unwanted pregnancy will ruin a woman’s life? The answer, to use a good but reviled word, is: hysteria. Almost all human beings occasionally give in to extreme anger and sorrow, which predictably leads to foolish decisions. Personality psychology shows that women are more prone to hysteria than men. And common sense tells us that pregnant women are much more prone to hysteria than other women. So we should hardly be surprised if women catastrophize their unwanted pregnancies. (The same holds, to a lesser degree, for men facing unwanted pregnancies).

Despite her conventional pro-choice views, Foster’s work shows that such catastrophizing is common. Yes, the vast majority of women who get abortions are glad they got them. But once they meet their babies, the vast majority of women denied abortions discover that they totally want their babies.

This massive status quo bias makes it hard to simply “trust women.” Which women should we trust — the ones who aborted, or the ones who couldn’t? But in the end, it is the women who were denied abortion who are more reliable. If shy people who don’t go to a party are glad they stayed home, and equally shy people who were pressured to go to a party are equally glad they went, the most natural interpretation is that the party-goers learned a valuable life lesson — and the home-stayers should have gone to the party.

Since Foster finds near-zero effect of abortion on subjective well-being, “Don’t get an abortion” makes sense as long as you assign any positive moral value to the unborn. But once you accept that the unborn have not minimal but intermediate moral worth, “Don’t get an abortion” has a buffer. If Foster had found that being denied an abortion reduced women’s life satisfaction from 3.3 to 3.1 for a full five years, you still shouldn’t get an abortion. That said, magnitudes matter. If she had found ten times that effect size (3.3 → 1.3) , I’d reverse my position.

If you’re paying attention, you’ll notice that I’ve said nothing about the legality of abortion. This is an essay about what you ought to do if you have a choice, so the arguments matter more when abortion is legal, and they matter most with abortion on demand. If you’re a woman with an unwanted pregnancy, or a man who has caused an unwanted pregnancy, it’s natural to hysterically conclude, “This will ruin my life.” But before you do, ponder Foster’s empirics — and Cromwell’s adage, “I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible you may be mistaken.”

That said, what are the implications for the legality of abortion? Even now, I remain undecided. I have a strong libertarian moral presumption, which implies a presumptive right to do wrong. The unborn are only of intermediate moral value, so maybe we should respect the right to wrongly abort. On the other hand, if abortion were currently illegal, it would be near the bottom of my list of liberalizations to prioritize. And if Sunstein-Thaler “nudges” are ever justified, they’re justified for abortion.

I know this is a quixotic essay. Almost everyone has long since made up their minds, and I’ll probably anger both sides. So why write it? My stock answer: Because I have something original, important, and true to say. Hysterically aborting your baby because you falsely believe the baby will ruin your life isn’t merely morally wrong; it is tragic. Why? Because before long, you almost surely would have loved that baby.

If there’s anything wrong with my argument, please let me know. If the argument is right, please start acting accordingly. And above all else, eschew hysteria.

* While the book is singly authored, the papers on which it builds had a wide range of co-authors.

—

I think it's odd you treat all embryos as equal. Human intuition, and law, typically considers a 2 week embryo to have dramatically less moral weight than a 20 week fetus. Lack of acknowledgement of that felt like an oversight in this post

There are a lot of problems with this sort of analysis, but the most obvious is that we generally aren't permitted to violate someone's autonomy just because there's a good chance they won't ultimately regret it being violated. I mean, just think about immigration - I'm sure a bunch of people who are denied entry into the US ultimately end up feeling good about their lives in Mexico or Thailand or whatever, but that's not a good argument for arbitrarily preventing their freedom of movement, right? Or you could even imagine something much worse, like child marriage, or bride kidnapping, or whatever. Just because people who are denied some right ultimately adjust to the results of that denial can't possibly justify the denial itself!

Also, for the record, I'd just say that plenty of people *don't* think an intermediate fetus has inherent moral value, and actually think there's no coherent or plausible analysis that says they do. I personally can't understand how value could exist on a sliding scale like that at all, or how it could be the case that something with no conscious experiences or psychological properties of any kind could be harmed in any way at all, which is all that should matter here.