The Sigmoidal Moral Value Function

What radiation, parenting, and the moral value of animals have in common

In Why Nuclear Power Has Been a Flop, Jack Devanney explains that pessimistic estimates of the danger of nuclear power rest on the assumption of linear harm: double the radiation, double the harm.

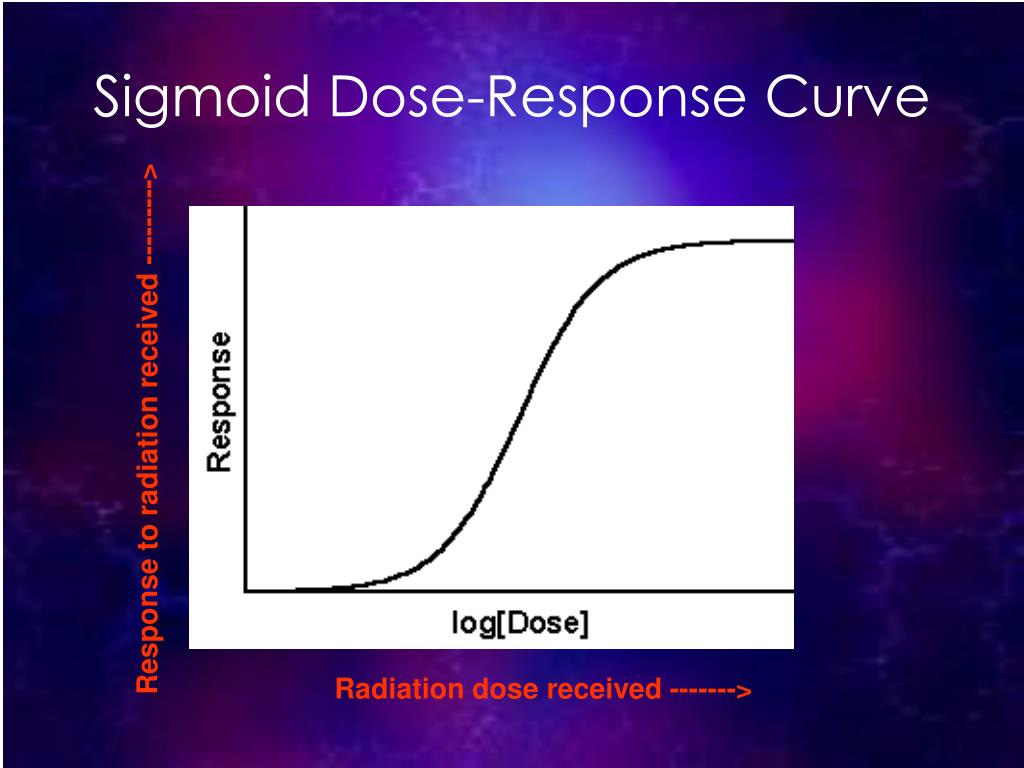

This linear assumption is blatantly wrong at high doses, because humans exposed to sufficiently high doses die with certainty, and you can’t double-die. Devanney argues at length that the linear harm assumption is also totally wrong at low doses. We can see this in the data: Low-level naturally-occurring radiation differs widely around the world, without noticeably altering the health of exposed populations are all. The correct harm function, he argues, is “S-shaped” or sigmoidal. Like so:

Devanney’s discussion of the sigmoidal dose-response function is not only compelling, but inescapable.

What’s the most familiar form of radiation damage? Sunburn. And as we all know, 100 minutes in the sun does not do ten times as much harm as 10 minutes in the sun! Instead, there is a sigmoidal dose-response function. 10 minutes in the sun does zero visible damage to even the lightest-skinned person, but 100 minutes will burn such a person to a crisp. Which is virtually the same effect as 1000 minutes in the sun! Devanney explains the underlying biology at length: Animals on Earth have evolved a cellular repair mechanism well-suited to counteract the mild radiation damage that animals on Earth continuously face.

I’ve known about Devanney’s arguments in favor of the sigmoidal model of the harm of radiation for a year or two now. Once I understood the model, however, I started to notice additional applications. Sigmoidal dose-response functions are common not only in the natural world, but in the social world.

Example: Picture a graph with “How much time I’ve spent with my kids” on the x-axis and “How much my kids like me” on the y-axis. At low doses, there’s near-zero marginal effect: You’ll be a stranger to your kids if you spend a lifetime total of one minute, one hour, or one day together. At high doses, again, there’s near-zero marginal effect. You’ll be a father to your kids if you see them for an hour every day or ten hours every day. Relationships are like radiation.

Only recently, however, did I realize that Mike Huemer’s “badness of pain” graph — a graph he created to ridicule my critique of ethical vegetarianism — is also sigmoidal! Behold:

I quite like Huemer’s graph, because it elegantly summarizes my view — which is also, not coincidentally, the common-sense view. For Huemer, however, this graph is bizarre. So bizarre, in fact, that the best explanation is moral gerrymandering to rationalize a package of bogusly convenient moral intuitions.

I’m happy to defend my moral intuitions on their merits. But once you realize that sigmoidal functions neatly fit much of the physical and social worlds, why should you be surprised to learn that sigmoidal functions also neatly fit the moral world as well?

P.S. I’d put chimpanzees somewhere in the middle of the steep part of the sigmoidal function. So if you want to crusade against the factory farming of chimps, I won’t stand in your way.

This could be your view, but it's definitely not the common sense one. There is nothing like common sense view surrounding animals and the badness of pain for cows is different in Europe and India.

Pigs are quite smarter than dogs, but the "common-sense" view would be that pain of dogs is worse than pain of pigs. Same for cats, parrots, pandas, any other cute animal. Most people are reaching for emotivism when discussing what behavior is wrong towards animals and it's mostly arbitrary/culturally driven. Even if you say, "but dogs are dumber" they would not get stampeded in this view, trust me I tried.

If you want to use the graph to describe your view feel free to do it, it's just not the common-sense view though, which means that your appeal to common sense morality as basis for your correctness is wrong.

Thanks for the post, Bryan!

"I’m happy to defend my moral intuitions on their merits. But once you realize that sigmoidal functions neatly fit much of the physical and social worlds, why should you be surprised to learn that sigmoidal functions also neatly fit the moral world as well?"

I would not be surprised by welfare being a sigmoidal function of cognitive capacity (although I prefer the square root of the number of neurons). The surprise comes from you placing a random human right after the steep part of the sigmoidal function, and all animals before it. Why does the steep part not start right after, for example, microorganisms, such that all animals are placed in the steep part, or after it? Adult pigs and cows are smarter than baby humans, so these have no moral value by your lights?