The Hidden Constraints on HOT Lanes

A guest post by Zixuan Ma

Bryan here. Last month, I blogged on “The Strange Economics of HOT Lanes.” Today, my co-author Zixuan Ma argues that two little-known regulations explain why “overpricing” is plausibly profit-maximizing after all. Enjoy!

Bryan Caplan raises a curious point in his essay The Strange Economics of HOT Lanes – if the private company in charge of congestion pricing on I-66 outside the Beltway is attempting to maximize profit, why does it seem to set the price so high as to keep the number of paying users low? Is it because the simple economics assumption of profit-maximizing firms fails in reality? Or are there hidden constraints that make the seemingly irrational price sensible?

As it turns out, the evidence supports the latter interpretation.

First of all, there is a real downside for the company if the speed is too low. EMP, the private company in charge of the toll, is indirectly bound by federal law which sets a minimum speed of 45 mph. If Virginia fails to maintain such a speed, the operating agency must file a corrective-action plan with the Federal Highway Administration. On top of the federal rule, the contract imposes an Operating Speed Performance Standard of 55 mph, with financial penalties and required remedial plans if EMP drops below it, presumably intended to create a buffer to avoid the federal speed floor. At the extreme, the contract may be terminated.

“The Developer shall provide a minimum average operating speed of 55 mph on the Express Lanes. …The facility is considered degraded by the OSPS when Compliance is ≤ 90 percent …”

— I-66 Express Lanes Operating Speed Performance Standard (OSPS)

“At any time after the occurrence and during the continuance of a Developer Default, the Department is entitled to terminate this Agreement….”

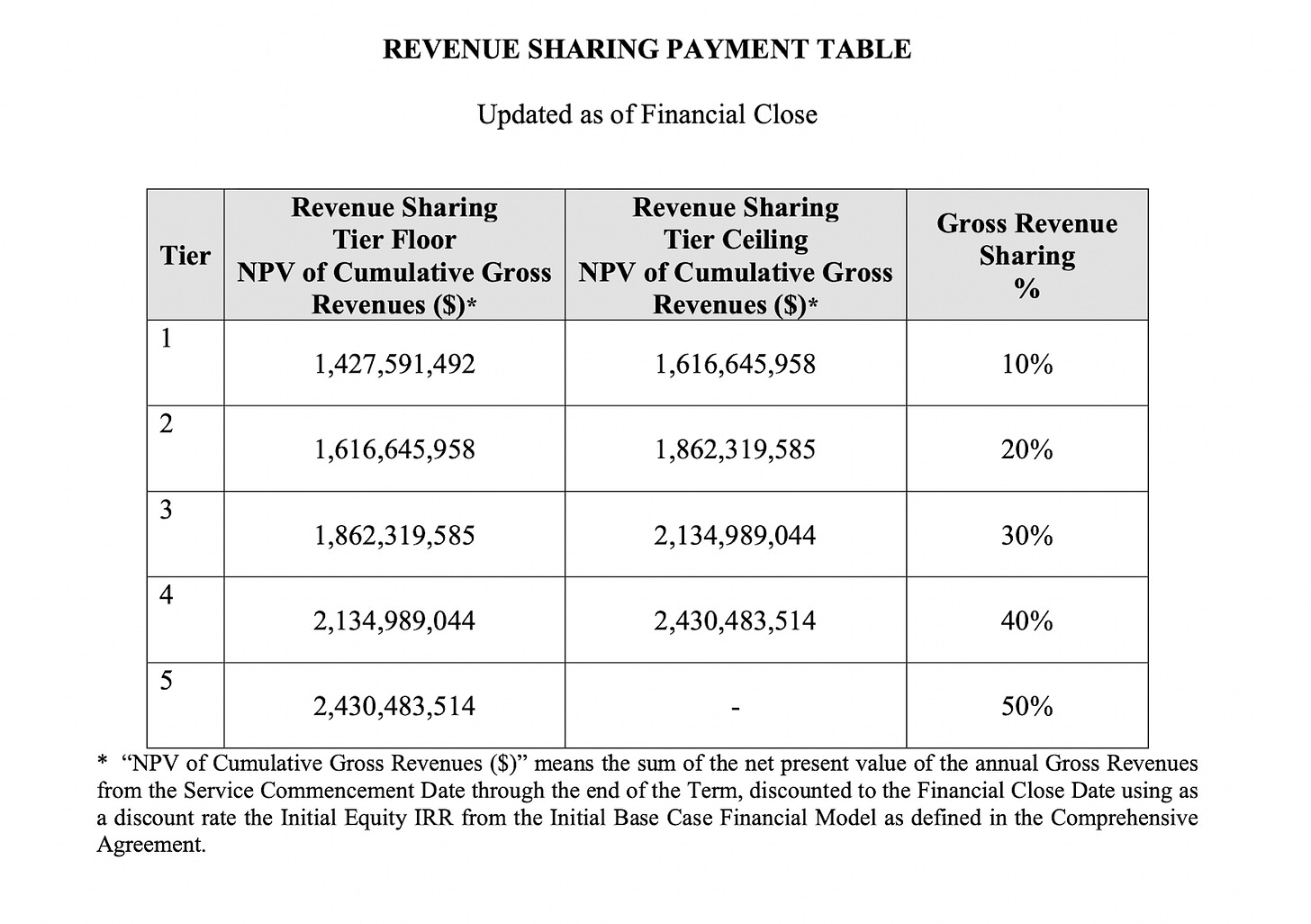

Second, the operator’s upside is flattened. The contract between EMP and Virginia states that once the return crosses certain “Equity IRR” thresholds, excess toll dollars are shared with the Commonwealth, with progressively higher shares as the excess return accumulates. The “tax” rates range from 10% in Tier 1 to 50% in Tier 5. Similar to the progressive federal income tax, it discourages risk taking by dampening profits.

Furthermore, the video in Bryan Caplan’s essay only shows one point at one time on the highway, the Jermantown Road Bridge. As the 55 mph speed floor applies across the highway, one has to observe the worst choke point at the busiest time of the week to obtain a more informative speed sample. Given the contractual speed floor, it is sensible for EMP to aim above 55 mph to build an additional buffer.

In conclusion, the company faces asymmetrical payoffs – penalty if the lanes are too slow, reduced profit share if the revenue is too high. As a result, it appears to adopt a rational toll to maximize profit subject to government-imposed constraints. In the real world, due to severe regulations and low risk combined with low return, public-private partnerships tend to attract conservative investors, not risk-taking innovators.

Although an improvement over free government-run roads, laws and regulations leave I-66 much less efficient than optimal. Why not charge in both directions at the same time inside the Beltway? Why not make all lanes outside the Beltway paid lanes? Why not charge tolls during congested periods on the weekends inside the Beltway? As Bryan Caplan notes in his upcoming book, the merciful maximization of the market is unfortunately often trumped by demagogic government, imposing what sounds good in place of what works well, to the detriment of society as a whole.

Zixuan Ma is a first year PhD student in economics at George Mason University, with broad intellectual interests and a focus on Chinese institutional economics. You can find him on X.

Bryan, I think you found a brilliant young mind to follow in your footsteps.

Thanks for writing this, Zixuan. I feel validated that my comment (link at end of this Note) on Bryan's prior post correctly recalled the incentives facing the toll operator, although I got the speed wrong: I mixed up the (not applicable here) 45 mph federally required minimum free-flow speed and the (very applicable) 55 mph required by VDOT and the P3 contract.

On your last paragraph, I think that "efficiency" is the wrong thing to look for: some people prefer to pay for peak travel traffic lanes with their time and some with their money, and it's not clear why the government should try to change that.

https://www.betonit.ai/p/the-strange-economics-of-hot-lanes/comment/114969328