"Aging Out" of Drug Addiction is the Norm

Abusers really do give vice a bad name.

The stereotypical drug user is a life-long addict. While stereotypes are usually good statistical approximations of the truth, I’ve long had the sense that this particular stereotype is false. The infamous heroin study, for example, found that the vast majority of U.S. soldiers who used heroin in Vietnam quit when they came home. Only recently, however, did I discover much more systematic evidence.

The source: Gene Heyman’s Addiction: A Disorder of Choice, published by Harvard University Press in 2010. In chapter 4, “Once an Addict, Always an Addict?,” Heyman tracks down nationally representative samples of drug users, finding that people in drug treatment programs are far less functional than the much larger segment of the population that has used drugs. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: Abusers give vice a bad name.

What exactly does Heyman have to teach us? Let’s start with the data:

There are four large national studies that recruited representative populations and provide data relevant to relapse and remission rates for addiction (Anthony & Helzer, 1991; Kessler et al., 2005a, 2005b; Stinson et al., 2005, 2006; Warner et al., 1995). Although these studies were conducted by leading researchers and funded by various national health institutes, the findings have not become a staple of discussions of the nature of addiction. For example, none of the clinical texts and journal articles cited in the introduction to this chapter reference these epidemiological studies. Thus, one of the goals of this chapter—and this book—is to introduce this information to addiction researchers as well as the public, although the research itself is not new.

The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study (1980–1984) is the earliest study. Results:

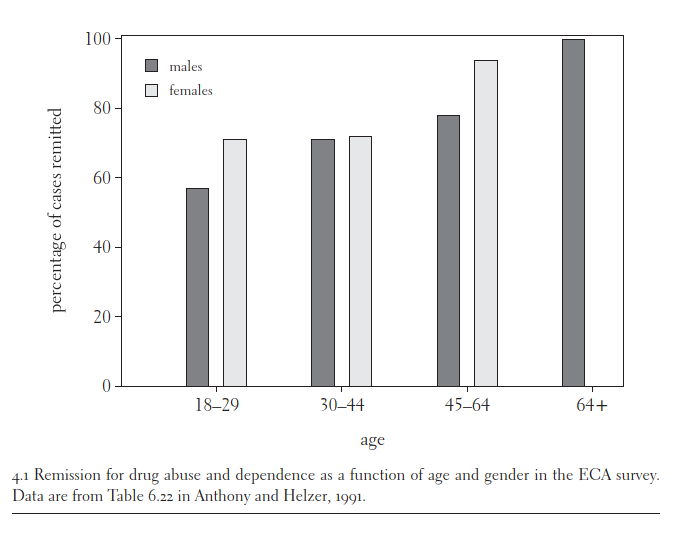

Remission rates in the ECA survey. The next figure summarizes the ECA findings on remission. It shows the percentage of individuals who reported no drug-related problems for at least twelve months prior to the survey, but had met the lifetime criteria for drug dependence or drug abuse (based on Table 6.22 in Anthony & Helzer, 1991). The data are organized in terms of gender and age. For example, according to the biographies, remission rates should top 50 percent by age 30.

Figure 4.1 shows that at approximately age 24 more than half of those who ever met the criteria for addiction no longer reported even one symptom, and that by about age 37 approximately 75 percent of those who ever met the criteria for dependence were no longer reporting any symptoms. Since dependence requires at least three symptoms over a twelve-month period, it is likely that the proportion of those in their thirties who were still dependent was actually less than 25 percent. Also note that it must be the case that most of those who quit did so outside of the purview of drug treatment clinics.

Next, Heyman reviews the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS), 1990–92 and replication (2001–02). Background:

In the early 1990s and then again in the years 2001–2002, Ronald Kessler directed two large, nationwide surveys of mental health and mental health services (Kessler et al., 2005a, 2005b; Warner et al., 1995). As was the case with the ECA study, the goal was to provide an unbiased scientific account of key characteristics of psychiatric disorders. The research reports emphasized the associations between different disorders (e.g., the correlation between depression and addiction), and hence the project was titled the National Comorbidity Survey. In addition to comorbidity, the measures included lifetime prevalence rates, current prevalence rates, age of onset, and demographic indices. But, in contrast to the ECA survey, nonmetropolitan as well as metropolitan areas were sampled. There were about 8,100 and 9,300 subjects in the two NCS studies.

Results:

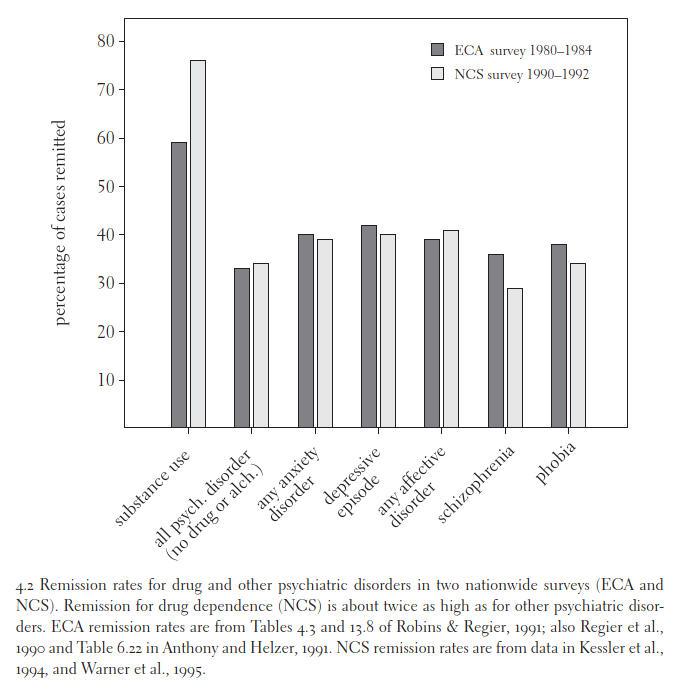

Figure 4.2 compares the remission rates for the ECA and 1990–1992 National Comorbidity surveys. Not counting addiction, the two surveys were in close agreement. The average (absolute) difference in remission rates was just 4 percent. For addiction, however, the two surveys came up with very different estimates of the percentage of “ex-addicts.” The NCS reported that 74 percent of lifetime addicts were in remission, an even higher rate than the ECA study (59 percent). This is by far the largest difference between the two studies.

The difference is due to two factors. First, the ECA survey used a much more liberal standard for counting current cases. Instead of the typical three symptoms, only one symptom was needed.

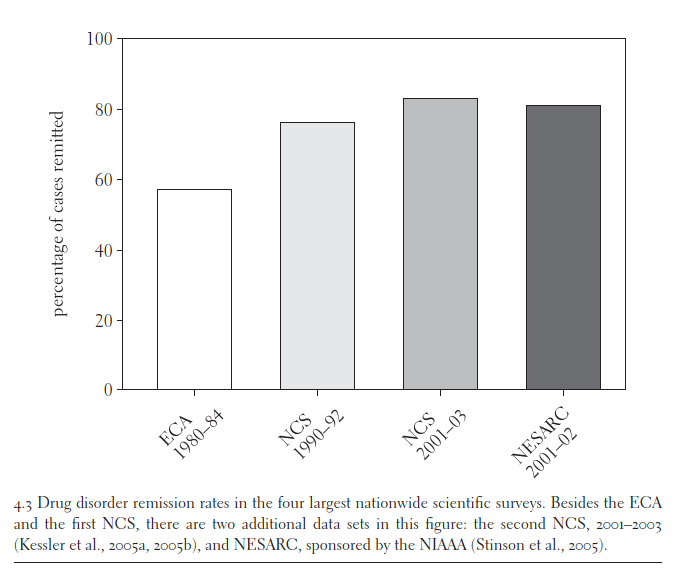

There were two more follow-up studies. All the results together:

In a nutshell: “Replication is the gold standard for scientific findings. By this criterion addiction is not chronic. Indeed, it could be said that it is just the opposite: self-limiting. Note that nothing has been said about treatment. This is because most of those who quit were not in treatment.”

Next Heyman considers the possibility that “remission” rarely lasts. News flash: Most heavy users really do “age out.”

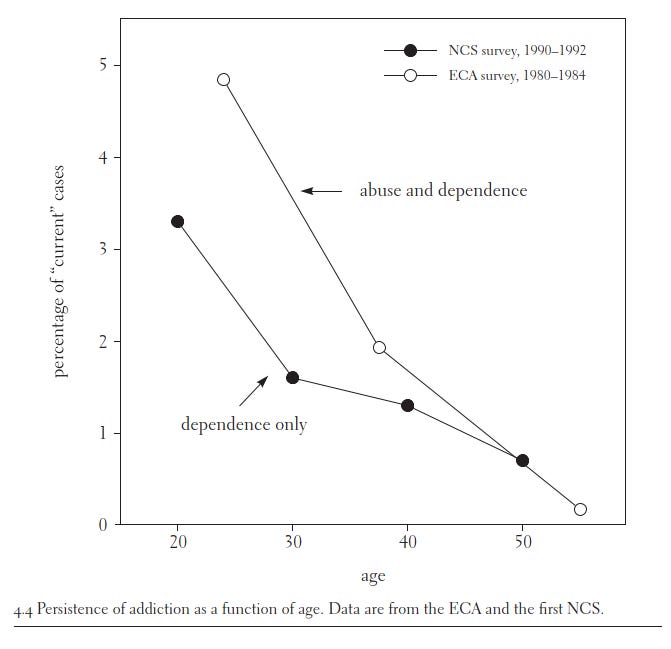

The idea that addiction consists of relatively short periods of heavy drug use followed by relatively longer periods of abstinence is easily tested. It predicts that one-time surveys will show that the overall rate of addiction remains approximately constant as a function of age. The next graph, Figure 4.4, tests this prediction…

For both cohorts, the age trend is sharply decreasing, suggesting that when those who met the criteria for lifetime drug dependence quit, they usually quit for good… To be sure, addicts may relapse the first few times they try to quit, but, according to the surveys, by about age 30 most have quit for good. Thus, for addiction, quitting drugs is more accurately described as “resolution,” not “remission,” when the ex-drug user is more than 30 years old.

Note that when these studies were conducted, overdose deaths were nowhere near high enough to explain the rarity of older users. While young users have elevated death rates, the vast majority survived long enough to quit.

Why do even many experts hold unrealistically negative stereotypes about drug users? Selection bias!

The simplest explanation of the discrepancy between the research findings and received knowledge regarding the nature of addiction is that experts are basing their understanding of addiction on addicts who show up in the treatment clinics, whereas the research reviewed in this chapter is based on studies that selected subjects independent of treatment history, with the goal of obtaining a representative sample. Both approaches would lead to similar results if most addicts ended up in treatment. But most addicts do not seek treatment. (emphasis added) Given that the clinic studies support the claim that addiction is a chronic disorder, this means that addicts who end up in treatment keep using drugs, treatment notwithstanding, and those not in treatment quit using drugs. This interpretation fits all the data presented so far, and it also suggests an interesting hypothesis…

First, it is reasonable to suppose that differences in pharmacological history distinguish the two groups.

Second, it is just as plausible that individual differences distinguish the two groups. These are not mutually exclusive explanations and both promise to increase our understanding of the determinants of drug use in addicts.

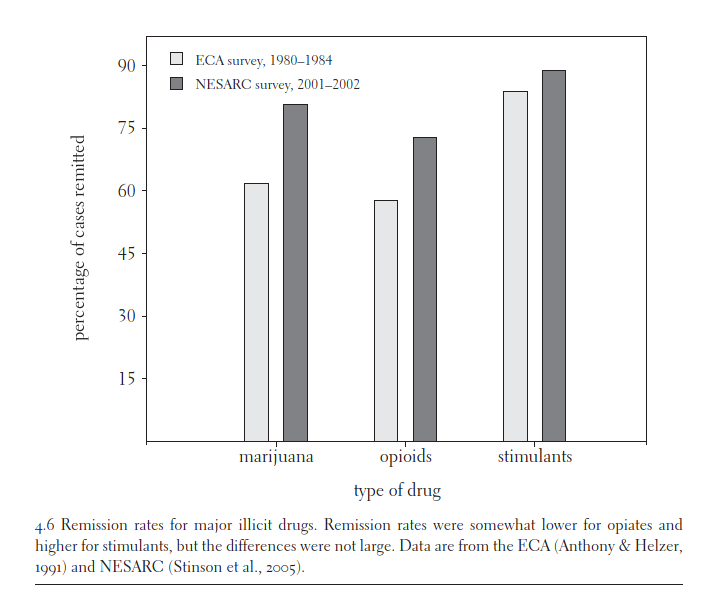

The first story is wrong: “The graph shows that the remission rates for the three drug classes did not differ markedly. The implication is that the higher remission rates for clinic addicts is not a function of using drugs that are more addictive.”

The second story, in contrast, is right. People in treatment programs are strongly selected for dysfunction.

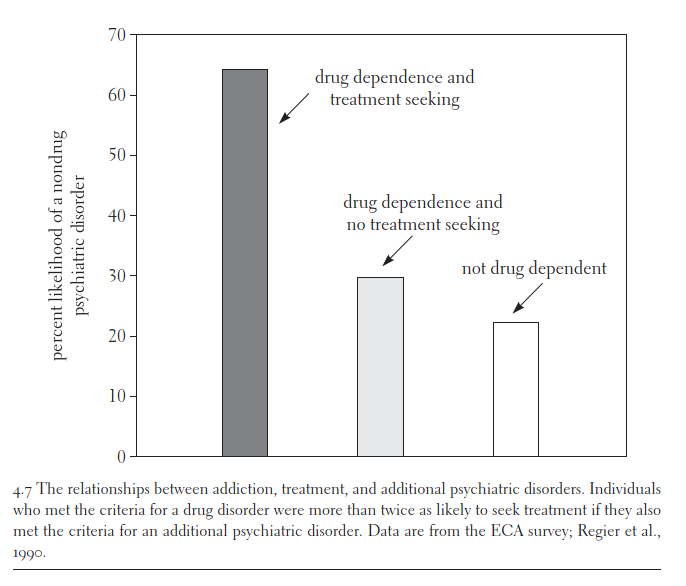

The most important is that addicts in treatment are much more likely to suffer from additional psychiatric disorders than those not in treatment. In the ECA survey the ratio was more than two to one (Regier et al., 1990). About 64 percent of those in the clinics suffered from at least one additional psychiatric disorder, whereas for those who said they had not sought clinic help for drug use, the comorbidity rate was about 30 percent, a number that is closer to the psychiatric prevalence rate for nonaddicts (see Figure 4.7).

Note: You don’t have to believe that “nondrug psychiatric disorders” are literally diseases to believe that people diagnosed with psychiatric disorders are especially prone to poor life choices! As Thomas Szasz quipped, “They are not disturbed; they are disturbing.”

Last question: How does “aging out” work in practice?

According to the biographies, financial and family concerns were among the main reasons addicts quit using drugs. Economics and family responsibilities are also the concerns of adulthood. This suggests that the pressures that typically accompany “maturity” bring drug use to a halt in many addicts. Assuming this to be the case, then one of the reasons that comorbidity promotes drug use in addicts is that it gets in the way of adult roles. It seems reasonable to suppose that those who are very depressed or very anxious are less likely to be engaged in activities that are incompatible with heavy drug use. Put another way, psychiatric impairment renders the drug experience relatively more valuable by undermining the ability to engage in and enjoy competing activities. The more general message is that whether addicts keep using drugs or quit depends to a great extent on their alternatives.

What difference does all this make? I don’t know Heyman’s view, but here’s mine:

While I would be horrified if any of my kids tried hard drugs, I’d also be horrified if my kids tried climbing mountains, racing cars, worshipping Satan, visiting Haiti, or even getting visible tattoos. Yet my horror does not show that these decisions are literal “diseases,” nor does it justify depriving my children of their freedom when they reach adulthood.

Medicalizing bad decisions is at best a Noble Lie. But once you realize that most people who make bad decisions eventually course-correct, the lie looks ignoble indeed. Why should everyone be deprived of their freedom to marginally help a tiny self-destructive minority? The righteous path is to harshly punish drug abusers for violence, threats of violence, theft, and trespassing, firmly stigmatize abusers, and stop losing sleep over the tens of millions of casual users who surround us.

Another explanation is that getting illegal drugs is hard and dangerous. As you age, you become less aggressive and willing to hang out with violent drug dealers since they might hurt you. That’s compatible with the family roles explanation but is less face saving since nobody wants to admit they are too scared to do drugs

Moral of the story is: if you find out your kid is addicted to heroin, don't worry about it! According to Dr Caplan, it's just a phase. They'll grow out of it!