What the Infamous Heroin Study Said

For years, I’ve been hearing rumors of a controversial study of heroin addiction among Vietnam veterans. The gist of the rumors: The vast majority of U.S. soldiers who were using heroin during the Vietnam War quit cold turkey as soon as they came home. Upshot: Addiction — even to heroin — is a choice.

I recently decided to track down this infamous study and read it for myself. The study is Robins, Lee, Helzer, John, Hesselbrock, Michie, and Wish, Eric. 1977. “Vietnam Veterans Three Years after Vietnam: How Our Study Changed Our View of Heroin,” Proceedings of the 39th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Committee on the Problems of Drug Dependence, reprinted in 2010 in the American Journal on Addictions. If you start reading the piece, I predict you will finish, because it is elegantly written.

Basics facts about the sample Robins et al. (henceforth RHHW) studied:

Dr. Jaffe asked me to design and carry out a follow-up study of returning veterans to learn the consequences of heroin use in Vietnam. In response, we interviewed about 900 of the 14,000 Army enlisted men who returned to the United States in September 1971, the first month in which this urine-screening and detoxification system was operating uniformly throughout Vietnam. The interviews took place between May and October of 1972, 8–12 months after their return (Robins, 1974). The men interviewed had been randomly selected from a computer tape of returnees provided by the Department of Defense. We also had access to the Surgeon General’s list of men who had been detected as drug positive at departure. A random selection from this list allowed us to oversample men detected as drug positive at departure. We did this to have a large number of men who would be at high risk of using drugs after their return…

In 1974, we selected 617 men for reinterview. These men were interviewed between October and December of 1974, 3 years after their return from Vietnam, at the average age of 24. We had reduced the sample from 900 to 617 to have enough funds to interview a non-veteran comparison group. We interviewed 284 non-veterans, matched to the veterans for age, eligibility for military service, and education and place of residence as of the veterans’ date of induction. The diligent interviewing team provided by the National Opinion Research Center secured a very high recovery rate of our target population for both interviews. In the first interview, we achieved 96% of the target population, and in the second interview 94%. Thus, we have two interviews covering 3 years since return for 91% of a random sample of Army enlisted men who spent an average of a year amid cheap, potent heroin.

Note: RHHW are focused on the drug use of veterans after their return from Vietnam. While they rely primarily on self-reports, they also ran some urine tests.

What questions did RHHW investigate?

First, does heroin use rapidly progress to daily use and addiction? Second, is heroin use so much more pleasurable than the use of other drugs that it supplants them? Third, is heroin addiction more or less permanent unless there is prolonged treatment? Fourth, does maintaining recovery from heroin addiction require abstention from heroin? Fifth, is heroin use a major social problem?

What did RHHW discover?

Heroin in Vietnam was very pure and cheap, leading to high rates of experimentation and use:

Practically every man we interviewed had had an opportunity to use heroin in Vietnam. Eighty-five percent of the men told us that they had been offered heroin while they were there — often quite soon after their arrival… Thirty-five percent of Army enlisted men actually tried heroin while in Vietnam, and 19% became addicted to it…

In Vietnam, where heroin was pure, 54% of all users became addicted to it and 73% of all who used it at least five times became addicted, a very substantial proportion indeed.

Nevertheless, “addiction” largely ceased after return to civilian life. Just 8% used heroin at all — and contrary to stereotypes, casual use dominated:

Less than half the heroin users used it regularly, that is, more than once a week for a month or more (Fig. 1). Users of amphetamines or marijuana were more likely than heroin users to become regular users, and barbiturate users were less likely. We find the same pattern for daily use. Only one-quarter of those who used heroin in the last 2 years used it daily at all, about the same proportion as amphetamine users, whereas about one-third of marijuana users were daily users of that drug.

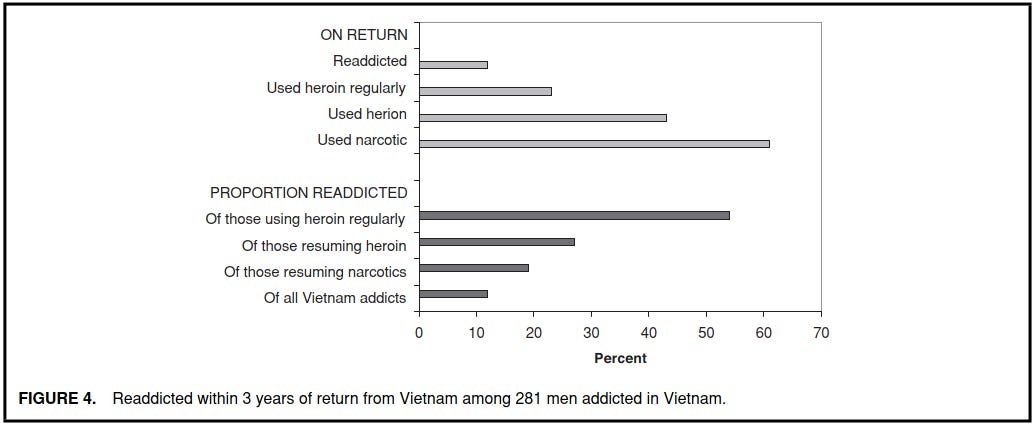

Looking specifically at veterans who were heroin addicts in Vietnam, “One out of five of our sample reported themselves to have been addicted to heroin in Vietnam, and that self-description was substantiated by their report of prolonged heavy use and severe withdrawal symptoms lasting more than 2 days. Only 1% of our sample reported addiction to heroin during the first year back from Vietnam, and only 2% reported addiction in the second or third year after Vietnam. Any sample in which the addiction rate drops so dramatically obviously contains many people experiencing long-lasting remissions. Indeed of all the men addicted in Vietnam, only 12% have relapsed to addiction at any time since their return, that is, at any time in the last 3 years.”

The paper’s key graph shows that the “vast majority quit cold turkey” rumors I heard were exaggerated. In fact, almost half of the men who were heroin addicts in Vietnam used heroin again at least once after their return to the U.S. But almost 90% did stop being addicts, and only about a quarter used heroin regularly.

Why didn’t veterans keep using heroin after their return? The answer, as this 2017 paper explains, is buried in the full-length report.

Robins asked why the veterans had not used heroin. It was not for lack of opportunity: most veterans reported that heroin was easy to obtain where they lived and a tenth had tried heroin after they returned. The main reasons for not using were a fear of becoming addicted, experiencing adverse health effects, being arrested and the strong disapproval of friends and family.

Even former heroin addicts rarely reported “cravings”:

Heroin addicts are supposed to continue to be bothered by a persistent craving for the drug long after acute withdrawal symptoms subside. To see if this was the case, we asked ex-heroin addicts who had not used any narcotic at all in the last 2 years if they felt like taking narcotics at any time, and if so whether it was a real craving or just a thought that crossed their minds. Only one-quarter reported that they had felt like taking narcotics, and only 4% reported a craving.

Heroin users used all drugs at high rates:

Heroin users are supposed to like the drug so well that they lay all other drugs aside in its favor. Our finding shows quite the contrary… One might think that perhaps it is only the heroin “tasters” who use other drugs—that men seriously involved with heroin would not be interested in less satisfying drugs. Again, the finding is just the opposite. It is the addicts who are most likely to be deeply involved with other drugs. When we asked men who told us that they had been addicted to heroin in the last 2 years (in response to a question, “Were you ever strung out or addicted in the last two years?”) about the use of other drugs, we found that addicts had used 10.4 other drugs on the average out of the 20 we inquired about, as compared to 7.9 for less regular heroin users.”

Veterans strongly believed that heroin use is dangerous and overwhelmingly oppose legalization.

Veterans themselves believe that heroin use is very dangerous. When asked what one drug had done the most harm in Vietnam, 90% of veterans named heroin whether they themselves had used it or not. The anti-heroin attitude of veterans is surprisingly resistant to their own experience. When asked if drug laws should be changed, and if so how, half of both veterans and non-veterans favored legalizing marijuana, but only 4% of veterans and 1% of non-veterans favored reducing penalties for or legalizing narcotics.

Heroin addicts were markedly more prone to crime and unemployment, but the shares were far below 100%. Furthermore, RHHW created a "Youthful Liability Scale” to measure pre-heroin propensity for poor outcomes “composed entirely of items ascertainable before the soldiers went to Vietnam (and thus before almost all of them were introduced to heroin).” Controlling for this YLS, they confirm that, “The men who used heroin were just those especially disposed to adjustment problems even before they used the drug.” Specifically: Occasional drug use — even of heroin — did not predict more bad outcomes. Regular use of any drug (except marijuana), however, was marginally so predictive:

The excess problems experienced by those who used heroin regularly (.9 more problems on the average out of 7) was no greater than the excess problems experienced by those who used amphetamines regularly (1.3) or barbiturates (1.1), and the association of heroin with social problems was less statistically significant than was the effect of either amphetamines or barbiturates. Thus, the reason that we find higher levels of social disability among heroin users than among users of other drugs is probably attributable to the kinds of people who use heroin. Men disposed to social problems are likely to use drugs, and those with the very greatest predisposition to social problems are the ones likely to use heroin. Yet regular heroin use does seem to have an added effect—whether because of the drug itself or because of its legal status, we still do not know. But its effects are no greater than the effects of regular use of amphetamines and barbiturates. These latter drugs constitute a more serious social problem than heroin, since they add at least as much to the level of social problems of users, and because so many more people use these drugs than use heroin.

RHHW’s big picture as of 1977: Official propaganda about heroin and heroin users is heavily laced with hyperbole. In their words:

Despite its reputation as a rapidly addicting drug, heroin in the forms available in the United States in late 1974 was no more likely to be used regularly or daily if used at all than were marijuana or amphetamines. It was more likely to be used regularly than other narcotics and other non-narcotic drugs. As compared with marijuana and amphetamines, what is distinctive about heroin is not its liability for daily use, but the fact that daily users perceive themselves as dependent. Despite their dependence, they manage to quit use much more often than anyone would have guessed and can often even return to use without becoming dependent again.

Furthermore:

People who use heroin are highly disposed to have serious social problems even before they touch heroin. Heroin probably accounts for some of the problems they have if it is used regularly, but heroin is “worse” than amphetamines or barbiturates only because worse people use it.

I’m not sure where I first heard of RHHW’s study, but it was probably Szasz-related: Substance abuse, like other “mental illnesses,” are preferences, not constraints. People don’t use drugs because they have to. They use drugs because they want to. I would be horrified if someone I cared about started using heroin. But that doesn’t mean that heroin users are “victims.”

I accept the casual use of the word “addict,” but the philosophical insinuation that “addicts” are incapable of self-help is deeply false. In fact, the majority of soldiers who were officially “addicted” to heroin during the Vietnam War really did go cold turkey after returning home. Only about 10% “readdicted.” The reason, to repeat, was not that heroin was unavailable in the United States, but that most veterans no longer wanted to use.

Yes, you could insist, “The 10% who readdicted had no choice.” But why assume that everyone who has a choice will choose well?

>but that most veterans no longer wanted to use.

The facts that heroin was illegal and strongly socially discouraged were pretty big factors. I don't think going "Most people stop doing heroin when the government puts lots of pressure to stop doing heroin, therefore the government can safely decriminalize heroin" makes sense.

Interesting study! I was unfamiliar with it. Could be though when they returned the price and search costs were higher. Doesn’t refute your point that use of drugs is a conscious choice, but just pointing out it also follows a downward sloping demand curve. See my papers with keith Finlay on methamphetamine which we found has an elasticity of -0.2 to -0.3 using two supply side shocks to the Input markets which caused huge increases in retail prices of meth. One was in economic inquiry and the other in health economics.