Why Politicians Should Stay Inside the Overton Window (Even When the Cause Is Just)

An pseudonymous guest post by "Chris Andrews"

Did abolitionism impede the fight against slavery? I think not, but my political scientist friend “Chris Andews” says I’m wrong. In response, he kindly agreed to write this guest post. Enjoy!

The politics of immigration show how positions far outside the center can undermine achievable reforms. Public opinion currently opposes the Trump administration and ICE tactics, but most voters also don’t support dramatic departures from existing immigration laws, such as open borders or blanket protections for all undocumented immigrants. During the year of our last presidential election, polling suggested voters still prefer Republicans to Democrats on immigration. Voters seemed uneasy with the Biden administration’s policies, associated with limits on deportations and reduced interior enforcement.

In the past ten years, politicians openly advocated for immigration policies far more lenient than what the voters want. In 2017, then Senator Kamala Harris tweeted that “an undocumented immigrant is not a criminal.” Meanwhile, Berkeley Mayor Jesse Arreguín said Berkeley “will remain a beacon of light … [a] safe space” for residents regardless of immigration status. The New Way Forward Act (H.R. 5383), introduced in 2019, would repeal key provisions of immigration law that criminalize unauthorized border crossing and rework detention requirements. In 2020, presidential candidate Bernie Sanders proposed a moratorium on deportations “until a thorough audit of past practices and policies is complete.”

Statements and policies like these make it easier for anti-immigration politicians to plausibly argue that there is no stable middle ground between aggressive ICE enforcement and wholesale decriminalization of illegal immigration.

I support a return to the mostly open border policies of the nineteenth century. But I don’t get to decide policy on my own. Recent public opinion polls, along with recent election results, remind me that public opinion needs to change before politicians can advocate for the changes I want. Biden administration policies that were out of step with broad opinion likely contributed to the backlash and the far worse immigration policies of the Trump administration. A politician advocating for my positions is more likely to produce see-sawing between extremes than the durable reforms we need.

This dynamic isn’t unique to immigration. A politician pushing for causes outside the Overton window may slow progress even when their moral case is compelling. We need to separate the functions of intellectual advocacy from the work of electoral politics. Writers and academics can expand what people believe is thinkable. Politicians in a highly nationalized media environment must win elections before they can enact laws.

Moral Advocacy vs. Political Campaigns

In any reform movement, there are two separate and important roles:

Expanding the range of what’s possible: showing people that the status quo is indefensible and that other futures are better.

Converting that possibility into law: building coalitions, navigating institutions, and securing electoral majorities.

Writers, academics, and activists do the first well. They help shift the Overton window — the set of policies perceived as politically possible — by making new ideas part of public discourse. A philosopher or economist may advocate for radically open borders and expand what people think about the issue.

But elected politicians have a different task. They must translate public sentiment into votes and then into legislation. When they adopt positions that are genuinely outside public tolerance, they can undermine the momentum for reforms that are actually attainable.

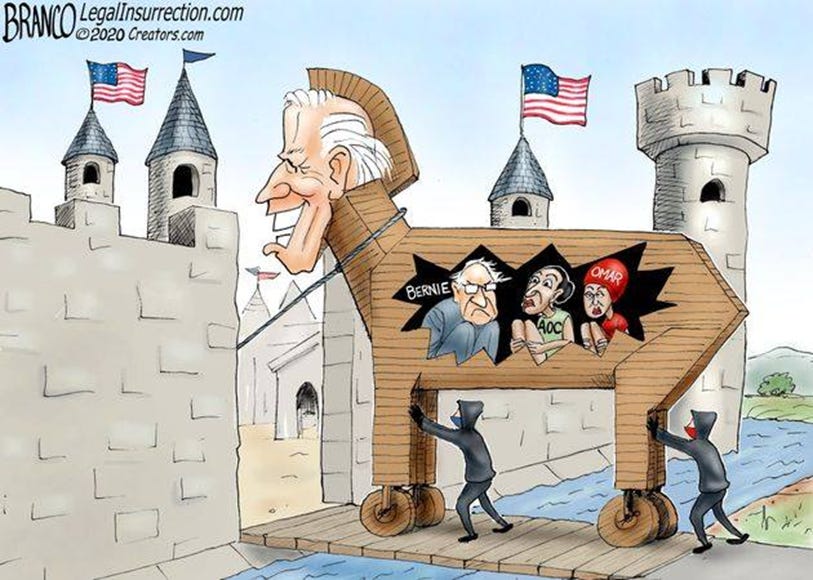

Moreover, modern media means that local politicians’ extreme statements are amplified nationally, shaping perceptions of the entire movement and giving opponents easy caricatures to deploy against centrist reformers. Social media doesn’t stop at the district boundary: a comment from a far-left member of the House becomes fodder for a presidential campaign ad in Iowa or a debate clip in Georgia, as depicted in the cartoon below.

Abolition as a Historical Analogy

Abolitionism in 19th-century America offers a powerful historical parallel. Early abolitionist thinkers were among the first to articulate an uncompromising moral case against slavery. These activists helped keep slavery in the spotlight even when political institutions accommodated it. Their advocacy laid the groundwork for later, broader public opposition. But passing policies required strategies and rhetoric that could actually win votes.

Many of the founders, while personally opposing slavery’s spread, deliberately chose not to enshrine an outright condemnation of it in foundational documents. Thomas Jefferson’s original draft of the Declaration of Independence included a paragraph condemning the transatlantic slave trade as “a cruel war against human nature itself” and slavery’s abuses. John Adams and Ben Franklin, while opposed to slavery, were part of the committee that struck such phrases from the document for political reasons. Insisting on the original phrasing would have likely fractured the unity necessary to defeat Great Britain. Founders at the Constitutional Convention also realized that banning the slave trade was the only practical limit within reach, and even that was postponed until 1808 in order to replace the Articles of Confederation with the Constitution. As Patrick Henry realized, the Articles of Confederation would have had far less ability to free the slaves down the line.

Later figures like David Wilmot, William H. Seward, and Salmon P. Chase stayed close enough to the political mainstream to fight for incremental victories. Wilmot designed a containment policy that, although it failed to pass in 1846, later became the platform of the Republican Party. Seward helped to admit California as a free state in 1850. As Governor of New York, he prohibited state officials from helping slave catchers and passed personal liberty laws that guaranteed juries in fugitive slave cases. Chase argued in court that slaves who entered free territories were no longer slaves, with some success before the Dred Scott decision. Abraham Lincoln himself opposed slavery’s expansion but was not an abolitionist. His moderate platform on containment helped him win the presidency in 1860. Even Seward and Chase were seen by many in the party as too strongly antislavery to win a national election, so Lincoln was nominated instead. Had Republicans lost the election of 1860, slavery’s abolition would almost certainly have been delayed.

Senator Charles Sumner represents a partial exception to the pattern. His uncompromising denunciations of slavery helped mobilize Northern public opinion, especially after being a victim of violence on the Senate floor. But Seward complained that Sumner’s uncompromising stance jeopardized his attempts to keep border-state unionists and other moderates in his coalition. After the war, Sumner’s purity isolated him from President Grant and cost him his chairmanship of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Even writers too far outside of the Overton window might hurt the antislavery cause. William Lloyd Garrison made the fight against slavery morally unmistakable. But because he rejected the Constitution and denounced moderate politicians, he provided pro-slavery defenders with a ready straw man they could use against more moderate restrictions on slavery. By contrast, figures like Frederick Douglass combined moral urgency with practical politics. Douglass embraced constitutional arguments against slavery, worked with Republican politicians, and often praised incremental change. Because he kept his moral stance within the political debate rather than outside it, he was harder for opponents to dismiss.

Relative to national public opinion, blue-city mayors and Democrats from progressive districts function more like Garrison, who could advocate for purity with no electoral cost. Like Garrison, they operate in ideologically homogeneous environments and face few incentives to moderate their rhetoric for swing constituencies. Seward, by contrast, calibrated his actions to fragile national alliances. Mayors and representatives don’t have to win Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, or Arizona or pass legislation through the Senate. But in an age of social media, they hurt politicians who do.

What This Means for Current Politics

Today’s polarized climate and 24/7 media landscape mean that every statement from an elected official gets a national audience. An extreme position in a safe district doesn’t stay local; it becomes a signal of their party’s perceived direction. When politicians adopt positions that are far outside what most voters support, they risk:

Giving opponents easy ridicule and caricature.

Shifting the Overton window away from achievable reforms.

Undermining coalition-building essential for passing laws.

This doesn’t mean politicians should never speak passionately or advocate boldly. It does mean that advocacy and electoral politics require different strategies. Writers and intellectuals should expand the moral horizon; politicians must navigate the political landscape to turn ethical imperatives into real reform.

When politicians should move closer to intellectuals will vary over time. In the early 2000s, it was understandable for some politicians to experiment with more expansive immigration rhetoric. But the electoral outcomes of 2016 and 2024 show that the current political environment is not the time or place for open borders signaling. Immigration helped a presidential candidate with no credentials and tons of baggage win an election no one thought he could win - twice.

Moral radicals and political pragmatists both have crucial roles in democratic change. Writers, academics, and activists can challenge assumptions and envision better futures. But when politicians step too far outside what the public is ready to embrace, they slow down progress on reforms that are within reach.

The author states he supports a return to something like the ‘open’ borders of the 19th century. Does he also support abolition of the federal welfare state in its entirety? As Milton Freedman has pointed out, you can have either a welfare state or open borders, but not both. Most of us know abolition of the welfare state is not possible, which fuels our opposition to relatively unrestricted immigration.

You do realize what you are saying: if the Overton Window doesn’t include freedom for all men, then some men must be slaves (at least until the window moves further from enslaving men to liberty for all men). That’s what Lincoln in effect represented; And Fredrick Douglass vehemently opposed on moral grounds.

Principles cannot be changed by election results, but a system based on majority rule will always be unjust and limit men’s liberty.

The Overton Window is nothing more than an excuse for violating principles (and replacing them with privileges for some) because men are not ready to be fully moral. That’s what the Overton Window explains.