The Sum of All Fears

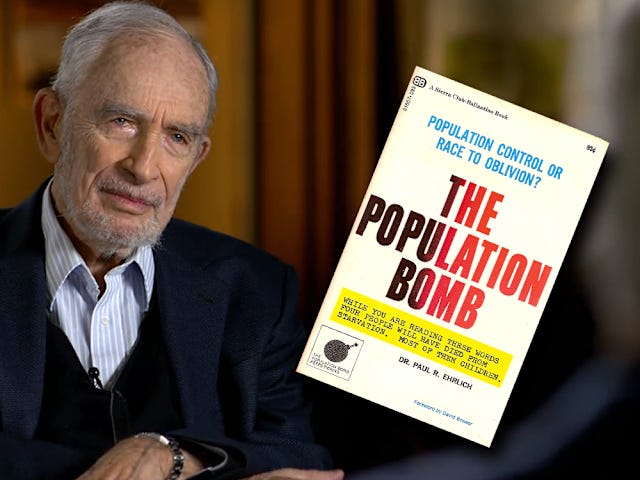

I didn’t think there was anything more to say about infamous doomsayer Paul Ehrlich. Until he decided to justify his career to the New York Times. Background:

No one was more influential — or more terrifying, some would say — than Paul R. Ehrlich, a Stanford University biologist… He later went on to forecast that hundreds of millions would starve to death in the 1970s, that 65 million of them would be Americans, that crowded India was essentially doomed, that odds were fair “England will not exist in the year 2000.” Dr. Ehrlich was so sure of himself that he warned in 1970 that “sometime in the next 15 years, the end will come.” By “the end,” he meant “an utter breakdown of the capacity of the planet to support humanity.”

Okay, here’s Ehrlich’s side of the story:

After the passage of 47 years, Dr. Ehrlich offers little in the way of a mea culpa. Quite the contrary. Timetables for disaster like those he once offered have no significance, he told Retro Report, because to someone in his field they mean something “very, very different” from what they do to the average person.

In the video interview, Ehrlich elaborates:

I was recently criticized because I had said many years ago, that I would bet that England wouldn’t exist in the year 2000. Well, England did exist in the year 2000. But that was only 14 years ago… One of the things that people don’t understand is that timing to an ecologist is very very different than timing to an average person.

Whenever smart people say things that strike me as absurd, I fear that this is what they’re thinking. But it seems paranoid. What expert with a shred of integrity would intentionally pull this bait and switch? Yet we have it from Ehrlich’s own mouth. He wasn’t wrong. Neither did he lie. He just deliberately used words that meant one thing to him and a totally different thing to almost everyone who heard them.

Notice that if this excuse were generally permissible, no one could even be wrong, much less dishonest. The horror!

True, this hardly proves that Ehrlich’s intellectual sin is widespread. But at least it’s an existence theorem. Some people really are doing the unspeakable. And given the intense incentives to never confess such activities, a single high-profile confession makes me fear they’re widely done. Ehrlich makes me feel like an epistemic germaphobe. Invisible corruption really could be swirling all around me…

The post appeared first on Econlib.

Ehrlich is remembered most thoroughly for being spectacularly wrong—no matter what ecological time filter he employs, nor whether he does so intentionally deceptively or merely in a revisionist manner—-and we don’t need to remove him from that pedestal. He and Al Gore look good together in that Hall of Clinkers.

Roger Pielke over at The Honest Broker has been doing good work demonstrating how much harm these wild-eyed, hair-on-fire doomsayers have done to rational scientific policy.

The bitter pill: your opponents will never acknowledge they were wrong, never say sorry, never pay any real price. You have to love truth for its own sake.