The Minimum Wage vs. Welfare: Band-Aid or Salt?

Peter Thiel entertains what economists would call a “second-best” argument in favor of raising the minimum wage:

“In theory, I’m against it, because people should have the freedom to contract at whatever wage they’d like to have. But in practice, I think the alternative to higher minimum wage is that people simply end up going on welfare.”

“And so, given how low the minimum wage is — and how generous the welfare benefits are — you have a marginal tax rate that’s on the order of 100 percent, and people are actually trapped in this sort of welfare state.”

“So I actually think that it’s a very out of the box idea — but it’s something one should consider seriously, given all the other distorted incentives that exist.”

Is he right? Maybe. A key insight of welfare economics is that one inefficient policy can counter-act another inefficient policy. But does this insight apply in this particular case? Let’s work through matters step by step.

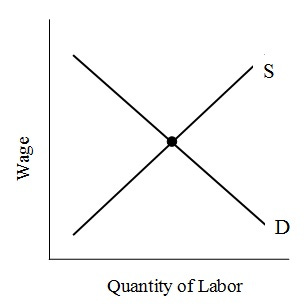

First, imagine laissez-faire. There’s no welfare and no minimum wage. The low-skilled labor market looks just like this:

Figure 1: Low-Skilled Labor Market Under Laissez-Faire

There’s no involuntary unemployment, and the big black dot reveals the wage and quantity of labor.

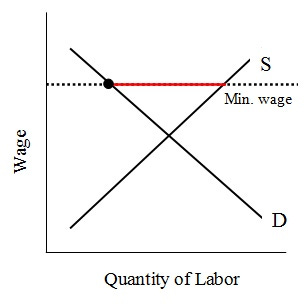

Now imagine adding a minimum wage – but no welfare – to the mix.

Figure 2: Low-Skilled Labor Market With Minimum Wage But No Welfare

The big black dot still reveals the wage and quantity of labor. Thanks to the minimum wage, though, there’s now a lot of involuntary unemployment, marked in red. This is true despite the fact that the minimum wage increases the incentive to work. Why? Because the minimum wage also reduces the incentive to hire! Since a deal only happens if both demanders and suppliers of labor consent, the quantity of hours worked is the smaller of quantity demanded and quantity supplied.

Under laissez-faire, any able-bodied worker can get a job and stand on

his own two feet. The minimum wage deprives the unfortunate workers

shown in red of their ability to support themselves. Given this involuntary unemployment, the case for welfare is suddenly easier to make. What happens if the government in its mercy puts the unemployed on the dole?

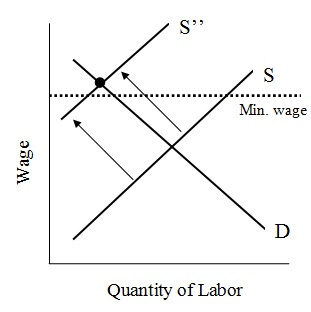

Figure 3: Low-Skilled Labor Market With Minimum Wage and Welfare

The answer may surprise you. The supply of labor falls to S’, of course, because free money makes workers less eager to work. But unless welfare is ample enough to push the market-clearing wage above the legal minimum wage, welfare has no effect on the wage or quantity of hours worked! Why not? Because thanks to the minimum wage, jobs are rationed. There’s still a line of eager applicants even if the marginal payoff for work declines.

With a binding minimum wage, the only clear-cut effect of welfare is to transform involuntary unemployment into voluntary unemployment. That’s why the red line shrinks: Some – though not all – of the workers who craved a job at the minimum wage now shrug, “Eh, now that I’ve got free money, why interview?”

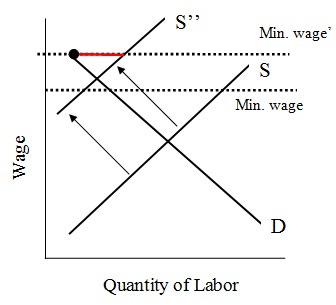

On Thiel’s story, though, Figure 3 doesn’t fit the contemporary labor market. He claims that welfare is now so generous that workers no longer desire minimum wage jobs. Diagrammatically:

Figure 4: Low-Skilled Labor Market With Minimum Wage and High Welfare

Notice: Sufficiently high welfare makes the minimum wage irrelevant. The market now clears at the intersection of the old demand curve D and the new supply curve S”. Since the intersection exceeds the minimum, the minimum has no effect. Thanks to welfare, employment is low. But whatever unemployment you see is voluntary.

OK, now we’re ready to see if Thiel’s story makes sense. Figure 4 roughly describes the world he thinks we’re in. What would happen if, swayed by Thiel’s argument, government raises the minimum wage to counteract welfare’s disincentive effects?

Figure 5: Low-Skilled Labor Market With High Minimum Wage and High Welfare

The answer, as Figure 5 clearly shows, is utterly orthodox: wages rise, employment falls, and involuntary unemployment revives. How is this possible? Simple. Generous welfare benefits do nothing to vitiate the truism that the minimum wage simultaneously raises the incentive to work and cuts the incentive to hire. And as usual, a deal only happens if both demanders and suppliers consent. The market therefore goes to the intersection of quantity demanded and the new minimum wage, with unemployment shown in red.

The lesson: When the minimum wage causes involuntary unemployment, raising welfare can serve as a band-aid for the labor market. Workers deprived of the right to provide for themselves can subsist on government money. Yet when welfare convinces people to abandon honest toil, raising the minimum wage is no band-aid. Instead, raising the minimum wage salts the wounds. The reason, to repeat: While a higher minimum wage does indeed make workers more eager to work, it also automatically makes employers less eager to hire.

I have great respect for Peter Thiel, but his concession to minimum wage advocates is confused. While some inefficient policies can offset the effects of other inefficient policies, the minimum wage is not such a policy. It doesn’t matter if welfare is high, low, or non-existent. The minimum wage causes unemployment by making marginal workers unprofitable to employ.

The post appeared first on Econlib.

Welfare is nothing else than a big employer who doesn’t follow any economic principles and creates a massive economic distortion. If that fake employer pays a high salary the opportunity cost of taking a true job is massive. But that fake employer buys millions of votes to politicians so the incentives are wrong. We all know the devastating effects of any price control mechanism but, like with socialism, we keep trying and trying the wrong recipe. Bottom line, we learned nothing

Thanks Bryan. I see the argument that raising the minimum wage doesn't increase the employment rate, even in the presence of welfare for the unemployed. But is it clear that raising the minimum wage doesn't increase aggregate wages paid? I assume that's the goal of those in favor of a minimum wage -- to increase the total quantity of the gains of trade that goes to labor. Surely no one thinks it increases the employment rate?

Separately but relatedly, one argument for the minimum wage that seems sensible to me, but that I've never seen spelled out, is that it would tend to modernize the economy. Long term elasticities are higher than short term elasticities -- in the short run companies may be forced to pay the higher wage, but in the long run they'll be more incentivized to figure out how to automate away those jobs. So the minimum wage acts as a sort of subsidy for the automation sector -- software, robots, AI, and so on. And in a different context, this kind of subsidy seems to be favored by development economists, who seem to think that employers of skilled labor don't capture all of the value of the training and modernizing that they provide, while employers of less skilled labor, such as farm labor, have smaller positive externalities, and they cite the history of which countries developed the fastest as evidence for this model, particularly in southeast Asia.

I'm not an economist, so as an outsider to the field I'm confused why the same people who think developing countries should favor tech over farming also use "elasticities are higher in the long run than in the short run" exclusively as a mark against the minimum wage. It's not a contradiction, but there is some tension there, no? I'd love to see this addressed in simple terms along the lines of this post.