The Hours and Academic Achievement

Adults love controlling the way kids spend the hours of the day. What’s the payoff for all their meddling? Hofferth and Sandberg’s “How American Children Spend Their Time” (Journal of Marriage and the Family) provides some fascinating answers for kids ages 0-12.

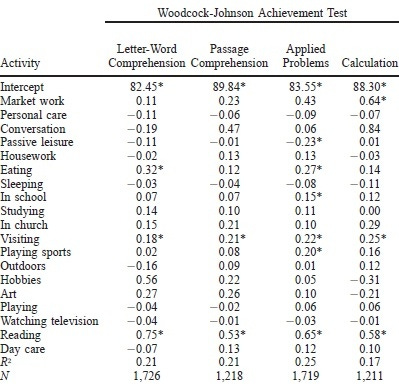

After compiling the basic facts about kids’ time use from the 1997 Child Development Supplement to the PSID, H&S regress measures of academic achievement on time use, controlling for child’s age, gender, race, ethnicity, head of household’s education and age, plus family structure, family employment, family income, and family size. All test scores have a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15, and all time use is expressed in hours per week.

Results:

The big result is the lack of results. Controlling for family and child background, time in school and studying barely help – and television viewing barely hurts. Contrary to wishful assertions that exercising the body improves the mind, sports don’t matter either. Out of nineteen activities, only two predict greater academic success across the board: reading and visiting.

The estimated effect of visiting is modest. Reading, however, is a huge deal. Ceteris paribus, 10 extra hours of reading per week raise letter-word comprehension by .5 SDs, and passage comprehension, applied problems, and calculations scores by .4 SDs. Despite obvious worries about reverse causation – smart kids enjoy books more – much of this is plausibly causal. After all, many smart kids don’t read much, and H&S include a lot of solid control variables. And you really can learn a lot from books.

I’ve long argued that the effects of parenting are overrated. H&S’s results lead to a separate but related result: How kids spend their time is overrated, too. If adults really wanted to raise kids’ test scores, they’d adopt the maxim, “If the kid has a book in his hands, leave him in peace.” Which, by sheer coincidence, was the maxim young Bryan Caplan vainly begged all the adults in his life to embrace. Reading rules, school drools.

The post appeared first on Econlib.