Suicide Versus Patriarchy?

Men notoriously have higher suicide rates than women. At least on the surface, this is a puzzle for feminism. If we really live in a patriarchy, if men really treat women so badly, why is it we men who are so much more likely to kill ourselves? One feminist response is to remind us that, “Patriarchy is bad for men, too.” As Laura Bates explains in The Economist:

Some sceptics will argue that feminism remains problematic because its true objective is not to achieve equality, but to advantage women at all costs, to the detriment of men. Many fear that focusing on women’s rights means neglecting men’s problems, such as the high male suicide rate.

Not so. I urge sceptics to take any issue that particularly affects men. It is often closely connected to the sort of outdated gender stereotypes that feminists are committed to tackling.

The tragically high male suicide rate, for example, cannot be divorced from the fact that men are far less likely than women to seek support for mental health problems. When we bring men up in a world that teaches them it’s not manly to talk about their feelings, we damage them terribly. And gender stereotypes don’t exist in a vacuum. They are two sides of a coin. In this case, the other side is the common notion that women are over-emotional, hormonal and hysterical; a cliché which disadvantages women in the workplace. Feminists are eager to dismantle these stereotypes, in all their forms. So tackling gender inequality at its root, as feminists seek to do, would help everybody, regardless of sex.

From a Bayesian point of view, this is a baffling response. If women had higher suicide rates that men, feminists would undeniably take this fact as evidence in favor of feminism. Therefore, as a matter of basic probability theory, the opposite pattern must be evidence against. Maybe not strong evidence against feminism, but the directionality is clear-cut.

Probability theory aside, there are clear predictions of the “Patriarchy causes the suicide gender gap” theory. Namely:

As gender roles become less traditional, the male/female suicide ratio will fall.

Societies with more traditional gender roles will have lower male/female suicide ratios.

How do these hold up? Poorly! Let’s start with the U.S. ratio from 1950-2018.

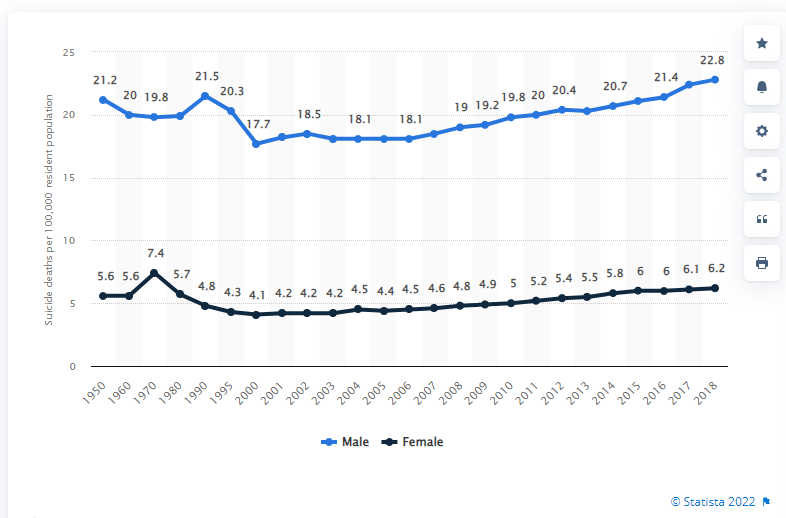

Deaths by suicide per 100,000 resident population in the United States by gender

Note that the time scale is not uniform, so the rough pattern (marred solely by the 1970 female suicide spike) is that absolute rates slowly fell from 1950-2000, then rebounded to near all-time highs. The ratio, meanwhile, started at 3.8, hit 4.7 in 1995, then fell back to 3.7 in 2018. If you only look at absolute rates from 1950-2000, you might convince yourself that the slow decline of patriarchy helped both men and women. Why, though, did the male/female ratio rise? Furthermore, how in the world could the patriarchy story explain rising absolute suicide rates since 2000?

International data is even less supportive of the patriarchal theory of the gender suicide gap. Sweden, Norway, and Denmark all have relatively low ratios, just over 2:1. Before you credit their gender egalitarianism, though, note that the ratio in infamously traditional Japan is about the same. India, one of the world’s most traditional countries, has a rock-bottom ratio of 1.3, roughly tied with Afghanistan. Iceland, culturally part of Scandinavia, has one of the world’s highest ratios, over 5:1. The only thing that can save the patriarchal theory is a severe case of confirmation bias. Well, I suppose you could also reverse engineer its success by proclaiming India and Afghanistan to be anti-patriarchal.

Reading Bates on the gender suicide gap reminds me of a seemingly unrelated quote from Joseph Schumpeter:

The theory that construes taxes on the analogy of club dues or of the purchase of the services of, say, a doctor only proves how far removed this part of the social sciences is from scientific habits of mind.

Similarly, I’d say: “The theory that blames patriarchy for the gender suicide gap only proves how far removed this part of of the social sciences is from scientific habits of mind.”

But what about “men’s rights” advocates who blame feminism for the suicide gap? They’re pretty obviously wrong, too. Take twenty minutes to actually look at the data. In the end, I think you’ll end up with this quasi-Socratic epiphany: If you’re not confused, you don’t understand what’s going on.

I think this argument is pretty weak. I agree that it's evidence against a simple "raise up men, cast down women" theory of patriarchy, which would probably guess that women commit suicide more. But if the theory of patriarchy is something like "extremize men, mediocritize women", then you should see more male extreme success and more male extreme failure (including suicide).

It's also not obvious that this is the right metric; as commented elsewhere, the 'gender paradox of suicide' is that women attempt suicide about 50% more then men do, and men complete suicide about 100% more then women do. (Suicide attempts are about 20x as common as suicide completions.)

| 2. Societies with more traditional gender roles will have lower male/female suicide ratios.

Isn't it supposed to say 'higher' male/female suicide ratios? As in, more male suicide?