Semi-Intellectual

A reply to Hyrum Lewis on *The Myth of Left and Right*

After Robin and I interviewed the Lewis brothers, they both wrote detailed replies. Here’s my reply to Hyrum Lewis’ reply. He’s in blockquotes, I’m not.

1. What are the three best bodies of evidence in your favor?

…We’ve found that these three lines of evidence (each backed by numerous studies) best militate in favor of our position:

Historical: Even a cursory look at history shows that what is considered left and right is always changing. Pro-market used to be considered “liberal” (e.g., Jefferson and Jackson) and then later was considered “conservative” (e.g., Taft and Reagan). Militarism used to be considered “liberal” (Wilson, Roosevelt, Truman—remember all those “right-wing” isolationists who didn’t want to get involved in WWII?) and then later it was considered “conservative” (Reagan and W. Bush). If some positions were essentially “conservative” then we would see conservatives embracing those positions across time and space. We don’t, indicating that there are no essentially conservative (or liberal) positions.

This is one example of why I’m convinced that you’re overstating, Hyrum. Suppose the “left” and “right” views change by 1% per century. I say that’s good evidence that essentialism is almost exactly true. Suppose that “left” and “right” views change by 1% per day. I say that’s good evidence is essentialism is almost totally false. The real world is in-between; therefore, the sensible position is also in-between.

Laboratory: Scholars have shown that they can get ideologues to switch positions simply by priming them with social cues. So if experimenters tell self-described “conservatives” that Donald Trump supports the minimum wage, those conservatives also support the minimum wage; if they tell self-described “conservatives” that Trump opposes the minimum wage, those conservatives also oppose the minimum wage (and the more conservative someone is, the more likely they are to follow the social cues). If support for the minimum wage grew out of an essential conservative philosophy or disposition, conservatives would draw their positions from that essence. They don’t. They draw it from their social group.

Reasonable, but notice that when intellectuals fail to respond to priming and proclaim their continued loyalty to “true conservatism” or “true liberalism,” you refuse to count this as evidence in favor of essentialism. Why not?

Survey: When we survey Americans about their individual political positions, we find no correlation between issues considered liberal (such as belief in abortion rights and belief in redistribution of wealth) except among those most socialized into believing in the political spectrum. If abortion rights and redistribution went together naturally because they both shared a left-wing essence, we would expect to see people holding those views in a package, regardless of their exposure to the left-right paradigm.

“No correlation”? Or just weak correlations? Again, I maintain that if “no correlation” supports the extreme version of your story, then a “weak correlation” slightly undermines that extreme version. The correct view is that the left-right spectrum is semi-intellectual. Largely social, but combined with some amateurish philosophizing.

6.a. Aren’t you holding essentialists to too high of a bar?

I don’t think so because we are holding them to the bar of falsification, which is what separates rationality from dogmatism and science from religion. All scholarly theories must be, in principle, falsifiable and yet the essentialist position has been, in our view, soundly falsified.

This is probably the most fundamental difference between us. I maintain that falsificationism is an absurd philosophy of science. No one - including you - applies it consistently. Essentialists could just as easily use falsificationism to “refute” you as you use it to “refute” them.

Why is falsificationism an absurd philosophy of science? “One failed prediction falsifies the theory” is the slogan. Yet even the strongest theories in physics get falsified every day. After all, high school students run experiments on Newtonian motion - and their results routinely contradict the theory!

The common-sense/Bayesian response is to scoff, “What’s more likely - that basic physics is wrong, or that high school students made mistakes?” In practice, professed falsificationists join in the scoffing. But they do so despite their philosophy of science, not because of it.

After all, once you declare, “Only a careful/skillful/reputable counter-example falsifies the theory,” people can cling to a theory by declaring counter-examples to be careless, unskilled, or disreputable. Then critics have to engage these declarations instead of just pointing confidently to the failed prediction.

Once we move away from natural sciences, falsificationism is even more absurd. Why do social scientists even bother doing statistics? Because no theory in social science perfectly fits the facts! In other words: Every one of our theories is easy to falsify. A devoted falsificationism has to jettison all of social science. The common-sense response, however, is to scoff, “So what? Social scientists should just use the least-bad theories we’ve got until better ones come along.”

If you ask, “Better by what standard?,” the answer is: “Better fits the totality of the evidence.” This, not falsificationism, is what “separates rationality from dogmatism and science from religion.”

Corollary: If the totality of evidence is already large, we shouldn’t dramatically revise our views in response to any specific fact. I’m happy to move from saying the Lewis brothers are 85% right to saying they’re 85.3% right. But it would be crazy to discover one new political fact that move from 85% to 100%.

Unconvinced, Hyrum? How would you respond if an essentialist announced, “The social theory predicts that issue positions will have a correlation of 0. The true correlation is .07, which soundly falsifies the social theory”? I predict that you would be unpersuaded. As you should be. Invoking falsificationism is tantamount to: “Hey everyone, let’s play this game with my stacked deck of cards.”

So, let’s go back to your claim that leftists are essentially anti-market:

What if the next president of the United States (with the help of a congress from his own party) was the most anti-market president in a generation—radically increasing spending, signing new economic regulations, running up debt, and significantly decreasing America’s “economic freedom” score—and yet the left hated him and the right loved him. Would this falsify your view that the left is essentially anti-market? If “anti-market” defined the left, then wouldn’t your theory predict that the left would love this extremely anti-market president?

If so, then the presidency of George W. Bush has already falsified your claim.

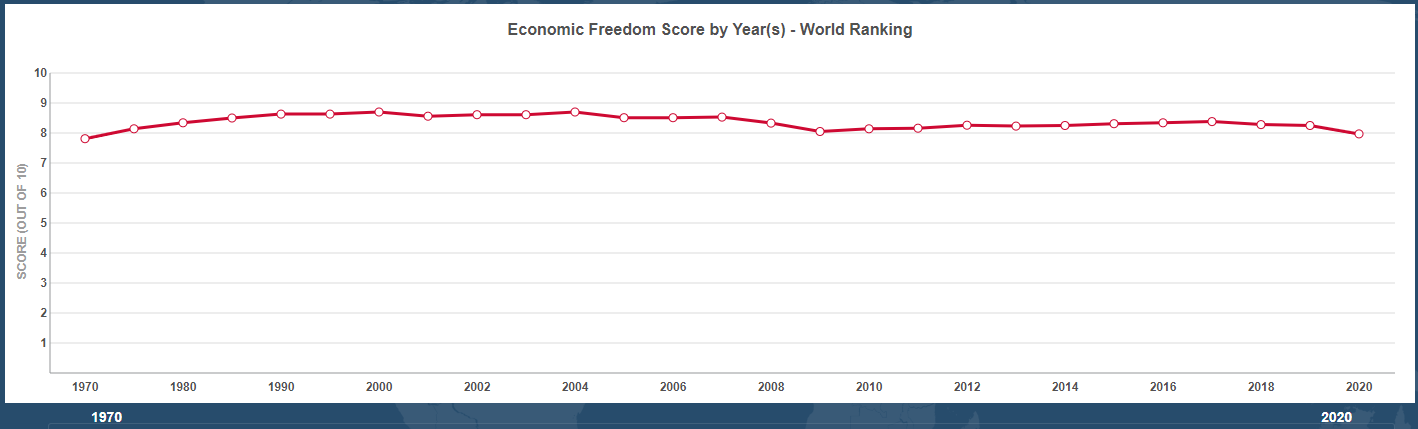

This brings me to another complaint about your book. While you make many sensible observations, you repeatedly treat totally debatable claims as established “facts.” According to the Fraser Institute’s measure, economic freedom was quite stable under George W. Bush. In 2000, the year before he took office, the U.S. score was 8.7/10. Four years later, it was still 8.7/10. In 2008, it was 8.33. That’s “the most anti-market president in a generation”?

Furthermore, even if measured economic freedom plummeted under Bush, you could blame other branches of the government. (When my old colleague Vernon Smith chided Bush on tariffs, that’s precisely how Bush responded).

Sure, you can object, “That’s what they all say.” I’m tempted to say so myself. But to treat the GWB’s performance as definitive proof of anything is deeply misguided.

We don’t use a unidimensional spectrum in any other complex realm of life for good reason (there is no single “business spectrum,” “medical spectrum,” “recreation spectrum,” etc.), so why do we use one in politics? We shouldn’t.

Actually, we use many such spectra. Masculine versus feminine. Smart versus stupid. Rich versus poor. None are perfect. Almost all are useful.

6.b. At any given time, leftist and rightist thinkers disagree, so there’s got to be some room for indeterminacy, right?

Yes, all categories have indeterminacy at the margins. For instance, we could show that there is indeterminacy in the category “chair”—which we might define as “a human-made device for human sitting”—by pointing to marginal examples, such as dollhouse chairs or stumps around a campfire. But the left-right categories are not indeterminate at the margins, they are incoherent at their core. To show why, let’s go back once again to your “anti-market” essence:

Adolf Hitler was not a marginal figure to the right; he’s considered the quintessential right winger—the purest, most perfect embodiment of the right-wing essence taken to its logical conclusion.

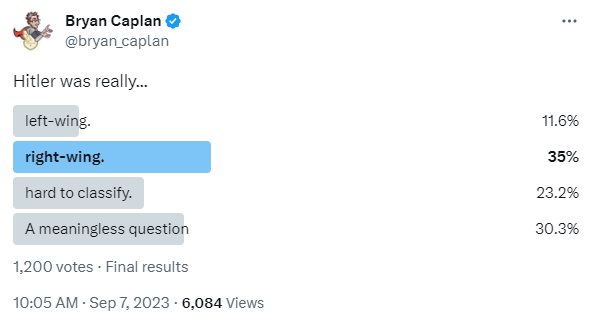

Again, you overstate. Leftists will often say this. Very few self-identified rightists will. Indeed, most rightists who confront this issue normally argue that Hitler was “really” a leftist. Check out this little poll I did:

And yet he was a proud socialist who believed in government nationalization of private industry and vast redistributions of wealth. Hitler was, by any measure extremely anti-market. So, according to the “anti-market” essence, Hitler should be on the “far left” (his anti-market views were even more extreme than the most radical Democrats today). The same is true of Tojo, Mussolini, and many other quintessential “far right” figures of the past century.

These are some of the big facts that motivate my Simplistic Theory of Left and Right. To repeat my position: The unifying idea behind leftism is antipathy for markets; the unifying idea behind rightism is antipathy for the left. The rest, on my account, is incidental. Hitler, Tojo, and Mussolini all count as right-wing despite their anti-market policies because they loudly criticized the left - and imprisoned and murdered many leftists for being leftists.

(Why don’t all of the millions of leftists Stalin murdered move him to the right-wing camp? Partly because he was far more anti-market than Hitler, Tojo, or Mussolini, but mainly because he explicitly killed leftists because they weren’t leftist enough!)

Donald Trump is not a marginal figure to the right; he’s considered the quintessential American right winger—a “far right” ideologue who captured the Republican Party and drove it to its extreme right wing—and yet Trump is far more anti-market than was Bill Clinton.

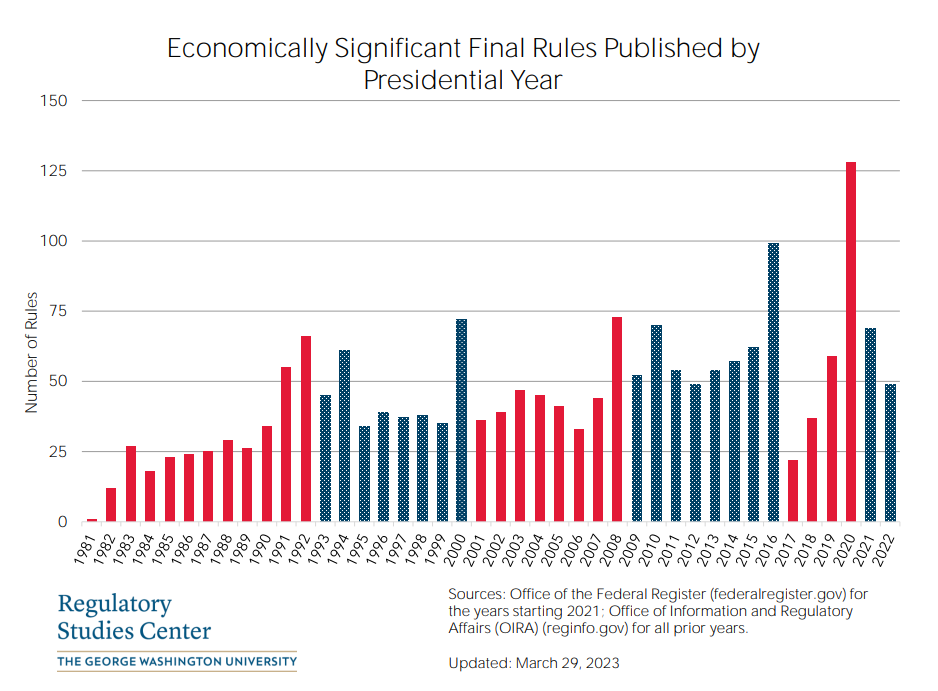

Another debatable claim stated as fact. Here’s a standard measured of the growth of regulation by year:

Yes, Trump has a huge spike in 2020. Covid, man. Almost anyone would have. Otherwise, Trump’s average looks lower than any president’s since Reagan. He also passed a major tax cut.

Misleading? Arguably. Using better measures, perhaps Trump was more anti-market than Clinton. But you speak as if this is an obvious fact that totally vindicates you. It’s not and it doesn’t.

So why does the left despise Trump and praise Clinton? When Trump and Bush moved the Republican Party in a more anti-market direction, we were told that they had both moved the party “to the right.” It seems to me that if your “anti-market” essentialist claim were correct, the consensus would be that Bush and Trump had moved the party “to the left.”

More thoughtful leftists repeatedly acknowledge that Trump isn’t clearly right-wing. Back in 2015, Ezra Klein called him “the perfect moderate.” In 2020, New York Magazine ran a story called “Trump Isn’t a Moderate, But He Plays One on TV.”

Of course, the falsifying evidence doesn’t stop there. Here’s more:

The War on Terror: if the left is essentially “anti-market,” why did the left (more than the right) tend to oppose the War on Terror and national security state more generally even though its expenditures and government controls reduced economic freedom? The essentialist theory has no answer, the social theory does.

My “semi-intellectual” story has an easy answer: This is one of the many issues where the social theory is true. Which doesn’t show that the social theory is the whole truth.

Immigration: if the left is essentially “anti-market,” why does the left currently want more of a “market” in laborers from foreign countries? The essentialist theory has no answer, the social theory does.

I’ve talked to quite a few pro-immigration leftists. Unless they’re economists, their main focus is not opening labor markets to international competition, but getting immigrants who are already here full access to government benefits. Furthermore, a lot of right-wing opposition to immigration is precisely that immigrants are coming for welfare, not work. Are these thoughtful positions? Not to my mind. But they are attempts to philosophically reconcile their specific issue positions with their general ideologies.

Drugs, Gambling, and Prostitution: if the left is essentially “anti-market,” why is the left currently more in favor of free markets when it comes to drugs, prostitution, and gambling? The right says “drugs kill people so we have to regulate the sale of drugs”; the left says, “guns kill people so we have to regulate the sale of guns”—why the inconsistency? The essentialist theory has no answer, the social theory does.

A big point in your favor.

Tech companies: if the left is essentially “anti-market,” why was Trump’s proposal to control the “liberal” private-sector tech companies considered “right wing”? The essentialist theory has no answer, the social theory does.

Most leftists - and many rightists - mock this as a betrayal of right-wing principle. I know you scoff at such rhetoric. But it still shows that what people “consider” right-wing is less clear than you think.

Mitt Romney: if the left is essentially “anti-market,” why is Mitt Romney considered to be more moderate (and therefore further to “the left” on the political spectrum) than Donald Trump even though he is far more pro-market? The essentialist theory has no answer, the social theory does.

If Romney had been elected, it’s not clear to me that he would have been more pro-market than Trump. Honestly, so many “facts” that seem clear to you seem murky to me.

11. You seem willing to accept sub-level essentialism, like “support for economic freedom” or “hawkish foreign policy.” But don’t all of your arguments about the logical independence (or “granularity”) of issues apply here, too?

Yes, but the difference is that some categories are accurate and useful and others are inaccurate and harmful.

At risk of sounding like a broken record: “Accuracy” and “usefulness” lie on a continuum. If you were so inclined, you could easily “falsify” the constructs of “support for economic freedom” and “hawkish foreign policy.” Just point out numerous changes over time, priming effects, low correlations, and inconsistencies.

12. Quote from p.79 on raw tribalism versus intellectualized tribalism. True?

Perhaps you could be a bit more specific, but I think our main point is that the highly intellectual are more likely to be tribal when it comes to politics because the essentialist myth is upheld by ex post storytelling and intellectuals are far better at concocting such stories. Intellectualized tribalism is also more pernicious than raw tribalism because it is less self-aware. We all have, for instance, the raw tribalism of American nationalism, but because we are aware of this tribalism, we are far more likely to be rational about it and question our nation and its leaders.

“Far more likely to be rational”? Do you remember bipartisan war hysteria after 9/11? I do.

We haven’t deluded ourselves with the myth that everything our nation does somehow flows out of a righteous philosophy.

Strange, I’d say that’s the standard bipartisan American view. The name of our “righteous philosophy” is “democracy.”

13. “The essentialist paradigm is making everyone stupid and evil.” Thinking again on a continuum, what’s the marginal effect?

One of the most common reactions to our rejection of the political spectrum, is the claim, “Well, it’s not perfect, but it’s useful.” People say this over and over, but never once to my knowledge has anyone provided any evidence for it. All of the scholarly evidence I’m aware of shows the exact opposite: those who think of politics in terms of a left-right spectrum are in a mental prison. They are far more dogmatic, hostile, closed-minded, and even unhappy. They can’t think as rationally or accurately as those who think outside the spectrum (Tetlock’s work on forecasting is pretty dispositive on this point). The spectrum is the opposite of useful.

You’re equivocating on “useful.” When researchers say that the left-right spectrum is “useful,” they don’t mean that it helps fix social problems. Indeed, even the most fanatical left- and right-wing ideologues almost never maintain that the spectrum helps fix anything. Instead, they maintain that their side of the spectrum fixes the problems caused by the other side of the spectrum!

When researchers claim that the spectrum is useful, what they mean rather is that using the spectrum helps us to understand political identity and political conflict. Which it totally does. No one has provided any evidence for this?! Every regression that shows that ideology predicts voting, issue views, or intermarriage is evidence. Want more? Read a few of Hanania’s brilliant essays on the intellectual and social anatomy of left versus right.

And so while we’re on the subject, I would ask you, Bryan: why do you continue to use the political spectrum when it is so obviously detrimental to the cause of freedom that you and I believe in?

I use the spectrum because it helps me understand the political world as it really is. Yes, I would like to believe that everyone and everything good is on “my side” and everyone everything bad is on the “other side.” But when I look and listen to other people in my political culture, that seems transparently self-serving.

By telling us that Bryan Caplan is essentially like Adolf Hitler because both of you are part of “the right,” aren’t you playing into the hands of statist authoritarians?

You can say that essentialism is 15% true without claiming that every leftist is “essentially like Stalin” or every rightist is “essentially like Hitler.” Personally, I claim neither of these things.

Denigrating freedom by conceptually tying it to its opposite (fascism) seems rhetorically destructive to the cause of liberty.

I agree, so I don’t. Even so, when fascists and communists fight for control of a country, I predict that libertarians will usually deem the fascists to be the lesser evil. Is that partly social? Of course. Is it 100% social? I think not.

The market economy has been perhaps the greatest force for social justice in the history of the world, and yet “social justice warriors” reject markets because the political spectrum tells them that favoring markets is somehow “far right” and therefore “fascist.” Why tarnish freedom with this false guilt by association?

This might explain why a few SJWs reject markets. Normally, however, the causation goes the other way. The left is anti-market. The fanatical left is fanatically anti-market. So if you breathe one good word about markets, the latter take the standard label for the worst kind of right-winger (“fascist” or “Nazi”) and stick it on you. A standard fanatical tactic. Denying the marginal explanatory value of the left-right spectrum won’t stop them from using this tactic.

Shouldn’t we just give up the fiction that there is one issue in politics, and instead say, “free markets are good,” “racism is bad,” “war is bad,” “immigration is good” and those are distinct issues?

They’re logically distinct and empirically connected. The empirical connection is modest, but on average, there’s a little logic to it. That’s not a fiction.

Why give people the false impression that you are a racist, anti-immigrant warmonger because you believe in free markets?

Do I give this impression?

The essentialist theory isn’t just bad for society and individuals, it’s particularly bad for freedom so I’m surprised that so great a champion of freedom as yourself is so determined to hold onto it.

Again, I hear an equivocation. I am determined to hold onto the left-right spectrum as a flawed but useful description of how politics actually works. At the same time, I would be delighted if these insipid ideologies themselves disappeared. What I won’t do is throw away a useful tool because I wish I lived in world where the tool didn’t work.

The remarks on falsificationism conflate the logical arguments concerning that epistemology with the practical difficulties of sometimes (but not always) applying it. https://jclester.substack.com/p/critical-rationalism

1) Foreign policy seems the most wishy washy of things. Hard to map onto left/right. Partly because domestic politics tend to dominate and how foreign policy affects domestic politics is complicated and shifting.

2) Obviously, the National Socialists were more pro-market than the Stalinists or Maoists. Hitler never outlawed trading or prices. There were no man made famines in Germany in peacetime. People used money, there were prices, etc. The entire schtick of the National Socialists is that they would solve the class warfare problem by turning the energy outwards and thus avert communist revolution. The fact that the KPD were Stalinist stooges didn't help.

This is why the industrialists endorsed Hitler. He seemed better than the KPD. If he had a more rational foreign policy then he probably would have been better then the KPD (and honestly, West Germany probably still did better in the end vs if there was a communist revolution, that's how bad communism is).

3) I still think "the most salient metric for equality" is the best metric for left/right. It explains the change from the left being pro market (when opposing divine right and noble titles) to anti-market (once we were politically equal but peoples value in the market differed).