Rational Irrationality in High Places

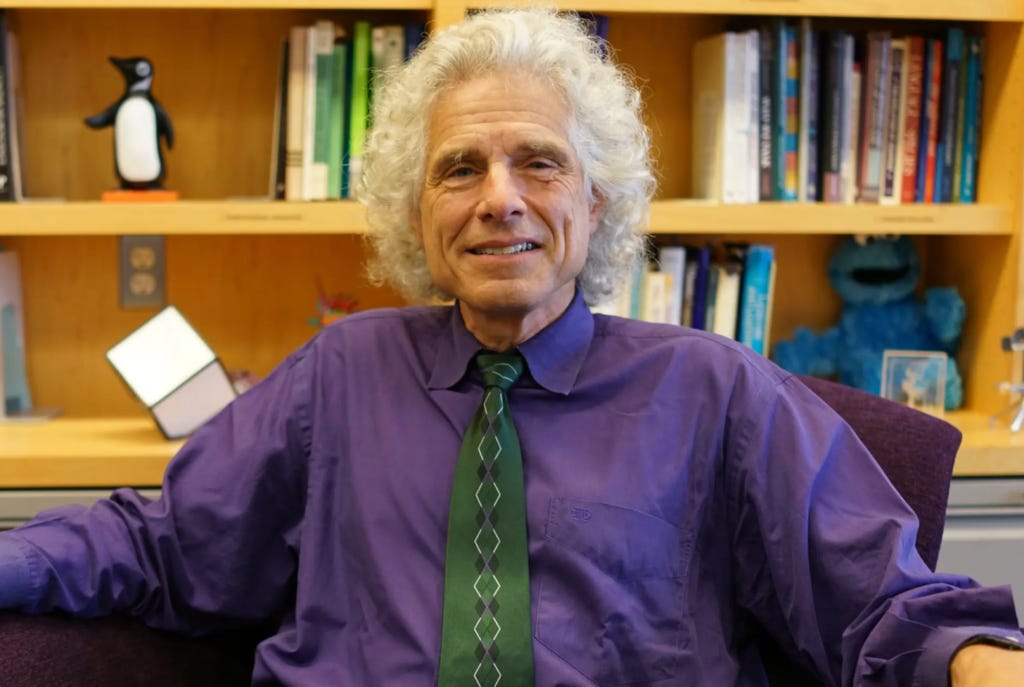

In the early 2000s, I coined the phrase “rational irrationality,” and later made it the foundation of my The Myth of the Rational Voter (and well as my case for betting). It’s very gratifying, then, to see that Steven Pinker is on board. From his recent interview with Richard Hanania, entitled “Rationality Requires Incentives.”

Richard: Yeah, I think that’s right. I guess, a different way to ask that question, is there a rationalist case against rational irrationality as far as, “Okay, I accept your arguments. I participated in this project of having a discussion and giving reasons for my belief.” But when it comes to religion, when it comes to politics, when it comes to my ultimate views of the universe, there’s no instrumental reason for me to believe in the truth. So I’m going to indulge in whatever I feel. And most people don’t think like this, but …

Steven: Actually I think most people do think in that monologue that you just shared…

Richard: Not consciously …

Steven: Not consciously, but I think, in fact, I think that’s a huge part of the answer to one of the puzzles that motivated the book. Namely, why does it appear that humanity is losing its mind? How could any sane person believe in QAnon or chemtrails, the conspiracy theory that jet contrails are really mind-altering drugs dispersed by a secret government program? And part of the answer is that people are in fact, most people, most of the time are rational about their day-to-day lives, about holding a job and getting the kids to school on time. They have to be. We live in a world of cause and effect and not of magic. So if you want to keep food in the fridge or gas in the car, you pretty much have to be rational.

But then when it comes to beliefs like cosmic, metaphysical beliefs, beliefs about what happened in the distant past and the unknowable future, in remote halls of power that we’ll never set foot in, there people don’t particularly care about whether their beliefs are true or false, because for most people and for most times in our history you couldn’t know anyway. So your beliefs might as well be based on what’s empowering, what’s uplifting, what’s inspiring, what’s a good story. And people divide, I think, their beliefs into these two zones. What impinges on you and your everyday life, and what is more symbolic, mythological?

It’s really only with I think the Enlightenment more or less that the idea that all of our beliefs should be put in the reality zone, should be scrutinized for whether they’re true or false. It’s actually in human history a pretty exotic belief. I think it’s a good belief, a good commitment, but it doesn’t come naturally to us.

The post appeared first on Econlib.