Raiding Woke Capital

“Go woke, go broke” runs the slogan, and there are multiple Twitter accounts that eagerly publicize alleged examples of leftist business leaders hurting their own companies. The Beckerian logic is straightforward: Businesses that care about ideology and profit will make less money than businesses that care about profit alone. The key question is empirical: Are firms run by “woke capital” putting enough weight on leftist ideology to drive themselves into bankruptcy?

So far, I see little sign of anything like a wave of woke bankruptcies. Disney is pushing its luck, but we’re talking about a phenomenally rich company with a unique product. Yes, a rival could build competing theme parks and competing children’s movies and competing superhero franchises. But even billions of dollars of investment would probably not recreate the devotion the public feels for Disneyland, Toy Story, or Marvel movies.

Disney is very likely taxing consumers’ devotion. But they could tax it far more and remain in business. The same goes for most woke companies. They can sacrifice 5% of their profits on the altar of wokeness without leaping on the pyre of financial extinction. In the long-run, perhaps even this marginal effect will kill off less-beloved companies. But this could easily take decades. And the truly beloved companies like Disney can plausibly forfeit 5% of their profits for ideological purity indefinitely.

In any case, suppose woke capital was indeed poised to drive Disney into the ground by the end of the year. Would this really be a good outcome? Of course not. A large majority of Disney shareholders probably disapprove of what current management is doing. Who wants to drain his portfolio promoting a cause he rejects? And think of all the kids who love Disneyland! Why should they lose out just because management wants to brainwash them?

What the world needs is a way to dislodge managers who sacrifice profit for woke prestige without waiting around for them to kill their own companies. A way to swiftly detach the parasite from the host while he’s still fundamentally healthy.

Wishful thinking? No. In theory, there is a simple way to remove subpar managers from any publicly-traded company: the hostile takeover. The classic version is just to buy 50%+1 of a firm’s stock, walk into the next board meeting, and fire the leadership en masse. Perhaps the most famous (and hilarious) historical example is Samuel “Sam the Banana Man” Zemurray’s hostile takeover of the United Fruit Company:

Wing [chairman of the board of the UFC] welcomed Zemurray without looking up, greeting him, as Thomas McCann characterized it, “frostily at best.” Zemurray waited as the board went through its tasks. When it was finally his turn to speak, he chose each word carefully, explaining his ideas in the thick Russian accent that he never could shed. It was the accent of neither the Russian bourgeois nor the peasant; neither the voice of Tolstoy nor the voice of Khrushchev. It was the voice of the Jewish Pale of Settlement, the Yiddish-inflected voice of our grandparents, the fruit peddler, the street haggler, the Yid.

When Zemurray finished, Wing smiled and said, “Unfortunately, Mr. Zemurray, I can’t understand a word of what you say.”

The men at the table started to laugh. Zemurray’s pupils narrowed to pinpricks, his hands turned into fists. He muttered, then stormed out. Perhaps the board members believed Zemurray had been chased away, was fleeing back to New Orleans. In truth, he had only gone to retrieve his bag of proxies. Returning to the boardroom, he slapped them on the table and said, “You’re fired! Can you understand that, Mr. Chairman?”

What followed was the sort of graveyard silence in which each board member recalculated his own prospects. “You gentlemen have been fucking up this business long enough,” Zemurray told them. “I’m going to straighten it out.”

Much later, analysts pointed out the flaw in the noncompete clause Zemurray signed at the time of the merger: it barred Zemurray from working for a rival or starting a new fruit company, but it did not foresee the outlandish possibility of Zemurray taking over United Fruit itself. “[I didn’t want to watch] the greatest company in the world go to hell in a hand bucket,” Zemurray explained.

Why haven’t hostile takeovers already stopped woke capital dead in its tracks?

Part of the answer, admittedly, is that executing hostile takeovers is intrinsically hard.

A bigger reason, though, is that existing regulations strangle hostile takeovers - a veritable death by a thousand cuts. The Williams Act, for example, forces would-be corporate “raiders” to publicly disclose their intentions in advance. This prevents the raiders from actually capturing much of the gain of the takeover. The classic strategy of quietly buying up shares, then summarily firing the current management, is off the table.

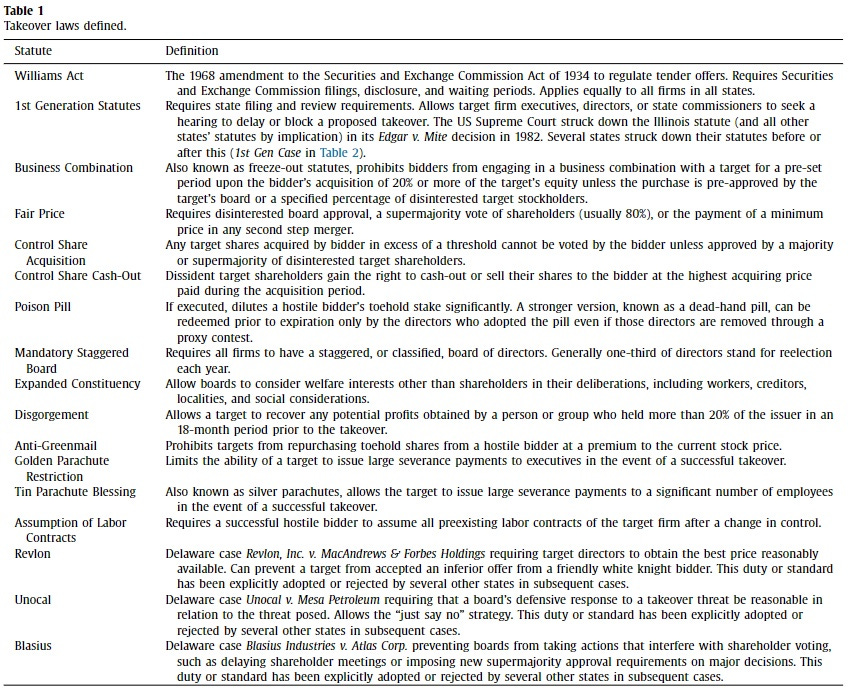

The Williams Act, though, is only the beginning. Cain et al.’s “Do Hostile Takeovers Matter?” (Journal of Financial Economics, 2017) provides this handy summary of the main regulations (and limitations on said regulations) that corporate raiders must navigate:

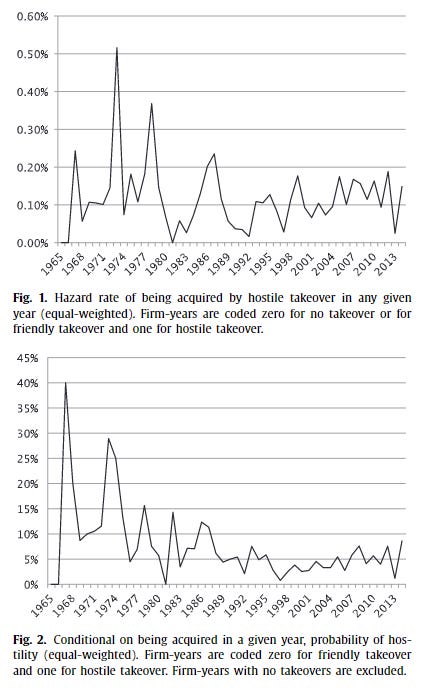

As you’d expect, hostile takeovers were a much bigger deal when regulation was minimal:

Cain et al. plausibly conclude that this is no coincidence: The laws designed to insulate managers from hostile takeovers largely work as intended. How the researchers know:

We use a data set of 17 different takeover laws and court decisions from 1965 through 2014 to measure the variation in takeover laws and their long-term impact on hostile activity. We also utilize a novel data set of Merger and Acquisition (M&A) hostility back to 1965. We find that the general susceptibility to a hostile takeover peaked in 1973 and has varied substantially since then. As a proportion of total M&A equal-weighted volume, hostile activity peaked in 1967 at 40% immediately prior to the enactment of the Williams Act and declined to about 8.6% in 2014.

What the researchers find:

Takeovers decline significantly following Fair Price laws and Assumption of Labor Contracts, as would be predicted given the potency of these laws. We also find that Revlon’s adoption incentivized hostile takeover activity, an event likely attributable to the heightened obligation Revlon placed on a board to consider such bids. Hostile takeovers declined in states adopting the Unocal standard and increased in states adopting the Blasius precedent. This is also in line with theory, as Blasius imposed tight restrictions on a target board’s ability to interfere with a shareholder vote that could unseat directors and force a takeover, and Unocal was seen as a more moderate test that gave wide discretion to the board’s ability to adopt defensive measures. Control Share Cash-Out laws increased hostile activity, which could reflect targets’ increased willingness to negotiate more aggressively due to their improved bargaining power.

Cain et al. is hardly the final word; as I’ve been saying for years, no paper is that good. But they make a noble effort, and their results fit common sense. Current law strives to keep bad managers in charge. Deregulation would unleash the wasted disciplinary potential of the hostile takeover.

Even if corporate raiding rises to new heights, of course, it won’t eliminate whatever wokeness consumers are willing to pay for. Niche firms might even become more woke than they already are. Since only a modest fraction of Americans are genuinely woke, though, deregulating hostile takeovers would largely lead business to stop willfully antagonizing the majority of their customers. Verily, as Michael Jordan aphorized, “Republicans buy sneakers, too.”

Historically, most scholars thought that incumbent managers wanted to hobble corporate takeovers so they could “enjoy the quiet life.” The threat of a hostile takeover prevents the leaders of publicly-traded firms from resting on their laurels. The logic remains the same, however, when managers’ breach of fiduciary duty stems not from sloth but from fanaticism. We need old-fashioned greedy capital to save us from woke capital. The good news is that greedy capital remains the norm. Free the latter-day Zemurrays, and they will unceremoniously get the business world back on track.

Or in the immortal words of Sam the Banana Man, “You’re fired, can you understand that, Mr. Chairman?”

The problem with the Beckerian logic in this case is that it ignores that being woke can benefit firms, if it significantly increases woke devotion to the company without alienating non-woke consumers. And as Nassim Taleb describes in Skin in the Game: "A Kosher (or halal) eater will never eat nonkosher (or nonhalal) food, but a nonkosher eater isn’t banned from eating kosher." Bowing to intransigent minorities can be profitable when it doesn't produce significant antagonism with other consumers.

Others have commented objections that wokeness might or might not be a disadvantage from the customer's point of view. I'd like to point out the "supply" side of the equation. For firms that are in any kind of creative business (and I define this loosely since it fits traditional creative, e.g. graphics, publishing, as well as non-traditional like money management, software development), they are in competition for talent and that talent might very well optimize personally for working in woke environments. So, yes, this pushes the woke "penalty" to the employee from the employer, but from the firm's point of view it's a win to be woke to the extent this is true.