Non-Competes Re-Reconsidered

An anonymous guest post

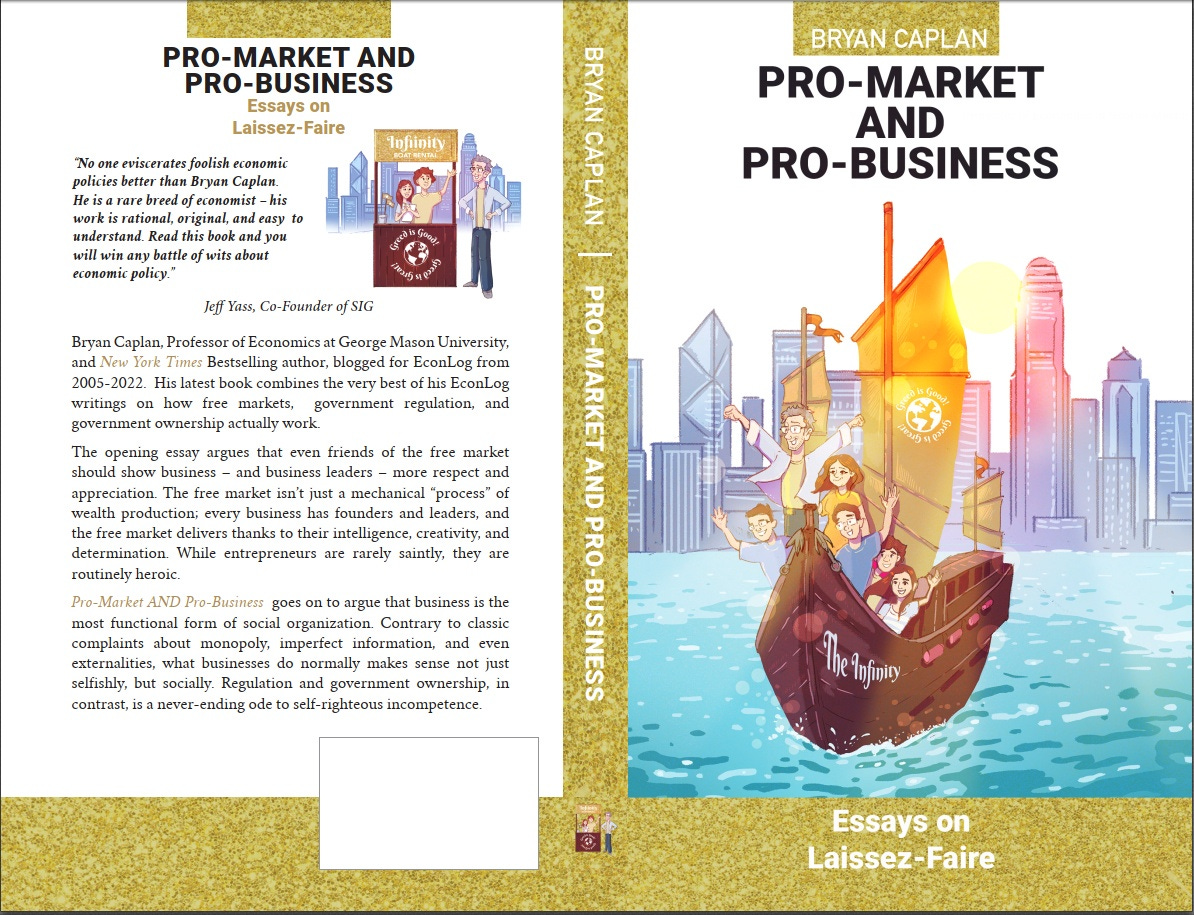

An anonymous reader sent me this critique of my “Dynamic Case for Non-Compete,” featured in Pro-Market and Pro-Business: Essays on Laissez-Faire. Enjoy!

You argue that non-competes can be beneficial since they make companies willing to share sensitive IP to employees. I have two responses to this post, which I would be interested to hear your thoughts on.

While trading firms would never say this publicly (because it sounds bad), I think that at least part of the reason that they have non-competes is game-theoretic. You can pay an employee with a non-compete less in the long run than an identical employee without a non-compete since the latter employee has more optionality.

Furthermore, I believe that most trading firm employees charge way too little for this loss of optionality, since despite being smart,

a. They’re way less sophisticated than trading firms, where teams of recruiters think about questions like “how much is this noncompete worth to us.”

b. Quant researchers are surprisingly bad at negotiation and tradery thinking (they’re shy nerdy types).

c. Even new grad quant traders are worse at job negotiation than you might expect.

Most employees don’t even think to put a number to the negative value of the loss of optionality and are not too far from price-insensitive takers of non-competes. I think that this is a major reason why it’s generally a good deal for quant finance employers to get employees to sign non-competes.

I’m skeptical of arguments that the above couldn’t happen because of the efficient market hypothesis (“why wouldn’t employees charge more?”) since the entire business of trading firms is to make money by finding places where markets are inefficient. “Prospective employees charge too little for non-competes” sounds a lot like the type of pattern that quant firms spend all day looking for! And the fact that these places all have non-competes is evidence that they all think employees are under-charging.

Main question here: do you think that if a trading firm said “Between you and me, if it were only for IP reasons, we would have a 30-day noncompete, but for game theoretic reasons we include an up to 3-year non-compete,” do you think that the portion of the noncompete which is 3 years minus 30 days is net bad for the world / leads to some form of deadweight loss? If yes, do you think there’s any good solution for this (e.g., in the form of banning or limiting non-competes)?

I can think of a different justification that a trading firm I’m familiar with might have for non-competes which I don’t believe you have mentioned in the past. I’m curious whether you think it is a good justification (both whether it is a plausible explanation for why companies might give non-competes, and whether it is a good reason that companies should be allowed to give non-competes).

I think this firm knows that it doesn’t have the name-brand of the very top firms. As a result, I think it is unusually good at recruiting from non-name-brand schools. To elaborate: the firm faces the problem that anyone from MIT or Harvard, conditional on accepting an offer, very likely applied to—and was rejected by—the top-name firms, and hence there is significant adverse selection when recruiting from MIT/Harvard. On the other hand, if the firm finds someone from Maryland that they think is very good, the firm has a good, non-adverse story for why they’d accept an offer—namely that the top-name firm likely didn’t interview them at all.

Consequently, I think the firm views the effort that goes into identifying talent similarly to intellectual property (e.g., developing a costly new drug or design), and this is connected to the fact that they give exploding offers with unusually long non-competes: if the offer didn’t explode, the student from Maryland could advertise their offer to a top-name firm and the firm would be exposed to the same adverse selection from them.

Hence, while the student from Maryland might be irritated by the exploding offer/non-compete, the firm might honestly say, “If we couldn’t give you an exploding offer with a long non-compete, we would not have taken the time to interview you in the first place, and would have stuck to bidding for students from MIT” (the same way that a pharmaceutical company wouldn’t invest in researching a long-shot new drug without the possibility for monopolizing its value for some time if it turns out to be valuable).

Final note: Your post refers specifically to concerns around proprietary information. However, I don’t think that the top market making firms teach anything very proprietary in their training to new hires. I think that the more accurate picture is that they invest a ton in their employees. (In general, specific secret things in quant finance have a short lifespan as secrets.) Trader training teaches a way of thinking--one which is very costly to teach since you need people who are very good at trading to teach it (you don’t want a mediocre trader teaching your new hires). But the cost of having a bunch of people who could be trading (each making many millions per year for the firm) teach full-time instead is very large. You’re only willing to invest this into a new employee if you know they won’t instantly turn around and leave. (This is closely related to point 2 above, but there the investment happens at the recruiting stage.)

My question here is: to what extent is the analysis in your post specific to concerns around sharing proprietary information? Or do you think the same analysis applies equally well to any way that firms might invest in employees? Do you think there’s a good argument for non-competes in any such case (for the same reasons we give patents to incentivize expensive drug development)?

1) Most times I've been asked to sign a non-compete it is after I'm already employed and usually with some kind of threat and a short timeline "sign this within thirty days or your fired". My bargaining power is such situations is basically non-existent.

2) I did once turn down a job offer at Amazon over what I felt was a very restrictive non-compete. After watching my friend get laid off by them and have that non-compete restrict him, I'm glad I didn't accept.

3) Only well into my career when I was financially comfortable and felt I had lots of options would turning down a job because of a non-compete make sense to me. If I was a new grad trying to get my foot in the door I would probably sign whatever the heck they put in front of me.

4) I think non-competes should be restricted to very high paying jobs. The more the job pays, the longe the non-compete can be for.

Had this anonymous reader ever read Rothbard, Hoppe or Kinsella, his whole understanding would have shifted, because he could then be able to comprehend that “intellectual property” is not property at all. His arguments are pointless if one accepts this stance.