Knowledge, Reality, and Value: Huemer’s Response, Part 3

Bryan’s Comments

“BC” indicates Bryan’s comments; “MH” is me (from the book).

1. Argument from Design

MH: Even if you’d never seen a watch before, you would immediately know that this thing had to have been designed by someone. It’s too intricately ordered to have just happened.

BC: The reason why we infer a watch-maker from a watch is not that the watch is “intricately ordered,” but that we have independent reason to believe that watches are not naturally occurring.

The “even if you’d never seen a watch before” is meant to exclude that. I.e., if you showed the watch to a person who had never seen (or heard of) a watch before, they’d still immediately know that it was an artefact. I assume that’s clear. That excludes the possibility that the conclusion is based on background knowledge about watches.

Maybe Bryan thinks they actually wouldn’t know this? Or he thinks there is some other reason for believing that watches are not naturally occurring? But I have no idea what this would be (?).

BC: Consider this rock formation: [image of Bryce Canyon]

Now compare it to this rock carving: [image of rock with heart carved in it]

The former is far more “intricately ordered” than the latter. But the latter shows design, and the former does not. Why? Because we have independent knowledge that only intelligent beings create rocks with little hearts on them.

Bryce Canyon is not really very ordered (though admittedly more ordered than just a big junk pile); you could move large parts of it around in lots of ways and not upset any salient pattern or activity. This is very unlike a watch: If you move parts of the watch around, for almost all ways of doing so, it stops working.

The rock carving has a simple order. But I don’t understand how Bryan thinks we know that it was carved by a person. I don’t know what “independent knowledge” he’s referring to. Maybe it’s the knowledge that a lot of people like heart shapes? Maybe it consists of having seen people drawing such shapes in the past?

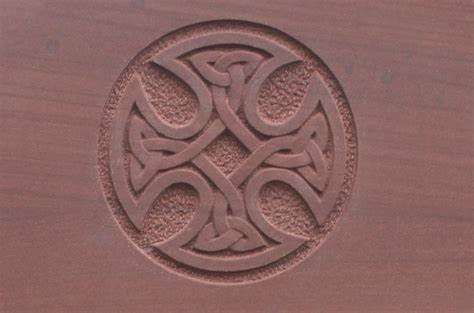

Suppose it was a rock with a different shape on it, one that you had never seen before. Like this:

I’ve never seen that shape before I found it on the internet just now. I bet a lot of readers haven’t either. I also have not looked up what that is, or whether it is natural or man-made. This one object is my entire sample of surfaces with that shape etched into them.

Q: Can I tell whether that’s man made? Yes, I can. I have zero doubt. This doesn’t rest on background knowledge about instances of that shape.

BC: But would it not be even more implausible to think that God just appeared by chance?

Theists standardly say that God either always existed or exists “outside time” (whatever that means), and often claim that God exists necessarily. They wouldn’t say that God appeared by chance.

Btw, I didn’t address this in the book, but sometimes people say, “But isn’t God himself even more intricately ordered than living things?” No; I have no idea why people say that. Theists typically think that God is a single, simple entity. God is not supposed to have organs arranged in a body, etc., the way you do.

2. Fine Tuning

MH: [W]hy does the universe in fact have life-friendly parameters? The theist says: Because an intelligent, benevolent, and immensely powerful being set the parameters of the universe that way, in order to make life possible.

BC: I say this is an obviously terrible argument, and I don’t say such things lightly. Why? Because we have zero evidence that the anyone can “set the parameters of the universe”!

I don’t know why Bryan thinks we have no evidence of that. The theist cited the evidence: the fact that the universe has life-friendly parameters. To say that we have no evidence of anyone being able to set the parameters of the universe, you have to assume that the evidence the theist just cited is not in fact evidence of what the theist says it is evidence of. That begs the question.

I note that this type of evidence is common, and it is not in general controversial that it counts as evidence (at least when we’re talking about things other than God). I.e., the fact that a seemingly improbable phenomenon exists, and that some theory would explain that phenomenon, is standardly accepted as evidence for that theory. That is in general how we have evidence for unobserved, theoretical phenomena (atoms, magnetic fields, quarks, etc.) And you don’t have to have some other evidence for those phenomena, independent of the inference to the best explanation.

I don’t know what view of evidence Bryan is assuming or why he claims that there’s no evidence in this case, so it’s hard for me to say more.

MH: [“Made by God” example]

BC: I’d say this is excellent evidence for intelligent English-speaking life on Mars, but zero evidence for God’s existence.

Zero evidence? So the probability of God doesn’t go up at all? How can that be? God isn’t even a possible explanation of the evidence in the story? The prior probability of God existing is zero?

I deliberately designed the example to be absurdly heavy-handed evidence pointing to God (theists can only dream of finding evidence so powerful and so obvious). I didn’t think anyone would have a problem with saying that ridiculous story would count as evidence for God if it happened.

BC: After all, everything on Earth labelled “made by God” is made by garden-variety intelligent English-speaking life, so why shouldn’t we make a parallel inference on Mars?

I’ve never seen anything labelled “made by God”, so I’m not sure what things Bryan is referring to. Of course, if I saw an ordinary object, like a shirt, labelled “made by God”, I would think it was made by a human being.

This, however, was not a plausible explanation in my example, because (i) there are no people on Mars before the astronauts go there, (ii) it was stipulated that the formations are consequences of the laws of nature. Human beings do not have the ability to design the laws of nature. If there is a being with the ability to design laws of nature, I would say that being has some fairly godlike powers. I suppose it could still be incredibly advanced aliens, but I don’t know why that theory would completely overwhelm the theistic theory.

3. The Anthropic Principle

MH: [Firing squad example]

BC: My reply: Entertaining such hypotheses only makes sense because we have independent reason to believe that people normally don’t survive fifty-man firing squads.

Again, I don’t know what independent reason Bryan is talking about. Explain it to me like I’m a baby.

I think it makes sense to entertain hypotheses for how you survived, because it is initially extremely improbable that you would survive the 50-man firing squad. Is that the independent reason Bryan is referring to? Or is that not enough, and you need some other reason? If so, I don’t know why Bryan thinks that you need some other reason.

BC: In contrast, it’s not weird for humans to exist on [a] planet hospitable to human life. And if you ask, “How did this happen?,” saying, “If the universe were very different, we wouldn’t be here [to] ask such questions” is illuminating.

I don’t understand at all why Bryan says either of those things, so I can’t respond to this other than to repeat what I said in the book.

It is weird for us to exist, once you know about the incredibly specific conditions required for us to exist. It’s weird because, well, it’s extremely improbable. Also, it’s true in the Firing Squad example that if the shooters hadn’t all missed, you wouldn’t be there to ask questions about it; yet that comment is not at all illuminating about why the shooters missed. Similarly, therefore, the statement “If the universe were very different, we wouldn’t be here to ask questions” is unilluminating about why the universe is the way it is.

BC: In any case, if you take fine tuning seriously, why can’t you just ask, “How did we happen to be in a universe where a divine being fine-tunes the laws of nature to allow our survival?”

You can ask that, but there’s nothing at all odd on its face about a conscious being deciding to create a universe that would have intelligent life.

This question strikes me as being no better motivated than the parallel question one could raise for any explanation. Someone posits X to explain evidence E. You can always say, “Why can’t you just ask, ‘How did it happen that X was the case?’” Well, sometimes you can ask that (perhaps always), but (a) this doesn’t mean that X doesn’t explain E, or that we should never make inferences to the best explanation, and (b) often X is less weird or more understandable on its face than E was.

4. Burden of Proof

BC: If X has a low prior probability of existing, and there’s no evidence of X’s existence, we should conclude that X has a very low posterior probability of existing. What gives X “a low prior probability of existing”? Many things, including (a) being very specific (e.g. X=”a guy with a feathered hat named Josephus who likes pickle-flavored ice cream and has exactly 19 hairs on his head”), and (b) being fantastical (e.g. X=Superman).

I note that Bryan is not defending the burden of proof principle as it is usually formulated, because the standard burden-of-proof principle claims that there is a burden of proof for any assertion of existence; it’s not limited to things with specially low prior probabilities (or it claims that every hypothesized entity has a low prior probability).

Anyway, I agree that the more specific the description of X is, the lower is the probability that X exists. But I’m not sure what counts as “fantastical”. In particular, I’m not sure whether the idea of a conscious being that can adjust the parameters of the universe is fantastical. If it is, then I’m not sure why we should think all “fantastical” things have a low prior probability.

5. Free Will

BC: My position, which I warrant Huemer would also accept: Libertarian free will and behavioral predictability are totally compatible. […]

I’m going to continue taking care of my kids. Still, this doesn’t show that I can’t do otherwise, only that I won’t.

Agreed. And that’s a good example. If you think that predictability (with high probability) rules out free will, then you’d have to say that when people do stuff that is obviously the only sensible thing to do, they’re not acting freely. Which is counter-intuitive.

Another example: I find someone living in a penthouse in Denver worth $3 million. I offer that person 50 bucks for the condo. I can predict, with very high probability, that the owner is going to turn down my offer. Surely that doesn’t mean that the owner’s decision to reject my offer is not free.

6. Degrees of Freedom

BC: I say, for example, that alcoholics are fully free to stop drinking. They rarely do, but they absolutely can. Indeed, there is strong empirical evidence that I’m right, because changing incentives changes alcoholics behavior; and if changing incentives changes behavior, that is strong evidence that you were capable of changing your behavior all along.

I would say that changing the incentives changes how difficult it is to stop drinking. The more difficult it is to stop, the less free the alcoholic is. The extreme of difficulty (the maximum level) is impossibility, and that is where the person is not free at all. Being “fully free”, or “maximally free” would be at the opposite extreme, where it is completely easy to stop drinking.

I think that view coheres with the fact that changing incentives sometimes alters the alcoholic’s behavior. It also explains why we blame someone less for bad actions that were, as we say, “more difficult” to resist.

BC: We condemn a starving man for stealing bread much less than a well-fed man for doing the same. The reason, though, [is] not because the latter choice is “freer” than the other, but because the latter choice is less morally justified than the [former].

Indeed, the starving man’s action sounds like it’s not wrong at all!

But not all cases are like that. You can imagine a pair of cases in which the action is equally justified objectively, but it was more psychologically difficult for one person to do the right thing than the other. E.g., maybe it was harder for A to do the right thing than B because A is a child and hasn’t yet developed good habits, or A was drunk, or A was very emotional at the time, or A didn’t have enough time to think about it, etc. Whereas B, faced with the same options with the same consequences, didn’t have any of those problems.

Then we’d blame B more. By stipulation, the reason can’t be found in a difference in the actions or the external conditions. It has to be about degree of responsibility for the action.

7. “The Soul”

Terminological note: Yes, you can basically write “mind” for “soul” if you prefer, and many people like that better. However, I take the term “soul” to be more specific. The term “mind” is neutral between physicalist and dualist (and idealist) views. The term “soul”, however, is not; it basically means “the mind on a Cartesian conception of it”. So most physicalists are happy to say that we have minds, but no physicalist would say that we have souls.

8. Hard Determinism

BC: In other words, determinism is a supremely unscientific theory that begins by throwing away ubiquitous conflicting evidence that each of us experiences in our every waking moment.

Yep.

Reader Comments

There are a lot of these, so I’m going to be really brief.

(a)

why huemer thinks the standard multiverse argument doesn’t solve this

I said that the multiverse is a viable explanation at the end of that chapter.

(b)

Sabine Hossenfelder argues that the fine tuning argument begs the question because it assumes a probability distribution that makes the constants of the universe unlikely…

The “Made by God” example was designed to (and does) refute precisely this view.

(c)

How does one really disagree with the idea that all human behavior can be traced to physical causes?

Partly by being a mind-body dualist!

(d)

The soul theory is subject to plenty of devastating reductio arguments as well.

I don’t think there are any devastating arguments there at all.

(e)

To know what we seem to observe, wouldn’t we first have to know what the options would look like? If both theories predicts the same observation, we can’t tell if we seem to observe theory 1 or theory 2.

I think this question conflates observation with inference or theory. You don’t observe a theory, and you don’t have to know anything about any theory to know what you seemingly observed.

(f)

…portrayals of Jesus in the Gospels aren’t implausibly specific.

Agreed. But I don’t think many people (and surely not either Bryan or me) doubt that Jesus existed. The issue is whether there is an intelligent designer of the universe.

(g)

“God did it” is not an explanation at all; it’s a declaration that no explanation is possible.

I don’t understand why the commenter said either of those things. Both are false on their face; “God did it” is an explanation, and it’s certainly not a declaration that no explanation is possible.

(h)

But the Wagerer must also make herself forget that she is going through the motions, instrumentally, in the hope of acquiring belief. She must act to forget-and-believe.

I don’t see why she would have to do that. There seem to be many people who do the sort of things I described, and they don’t have to forget doing them. E.g., many people only watch “news” sources that support their ideology, they don’t forget that they’re doing this, and they have no trouble believing their ideology.

(i)

why does Philosophy accept the descriptions of Gods given by the worshippers? They are almost certainly inflated. […] If God is as great as the believers make him out to be, humans are probably an unimportant side-show.

Fair points.

If God made the universe, there are probably many other planets with life out there, so God would not be focused on Earth in particular.

(j)

If Determinism is established, then we will continue to do what we have (and will) be doing.

This assumes that the establishment of determinism would not itself have any causal powers. But it would (just like all the other events in the world).

The post Knowledge, Reality, and Value: Huemer’s Response, Part 3 appeared first on Econlib.