Immigration, Innovation, and Half-Truths

Critics of low-skilled immigration usually lament their effect on low-skilled natives. Once in a while, however, the critics bemoan the effect of low-skilled immigrants on robots. Without low-skilled immigrants, there would be a much stronger incentive to mechanize agriculture, deliveries, driving, gardening, and beyond. Indeed, without low-skilled immigrants, we should expect much faster innovation for a vast range of labor-saving technologies. As J.D. Vance explained earlier this year:

[C]heap labor is fundamentally a crutch, and it’s a crutch that inhibits innovation. I might even say that it’s a drug that too many American firms got addicted to. Now, if you can make a product more cheaply, it’s far too easy to do that rather than to innovate.

And whether we were offshoring factories to cheap labor economies or importing cheap labor through our immigration system, cheap labor became the drug of Western economies.

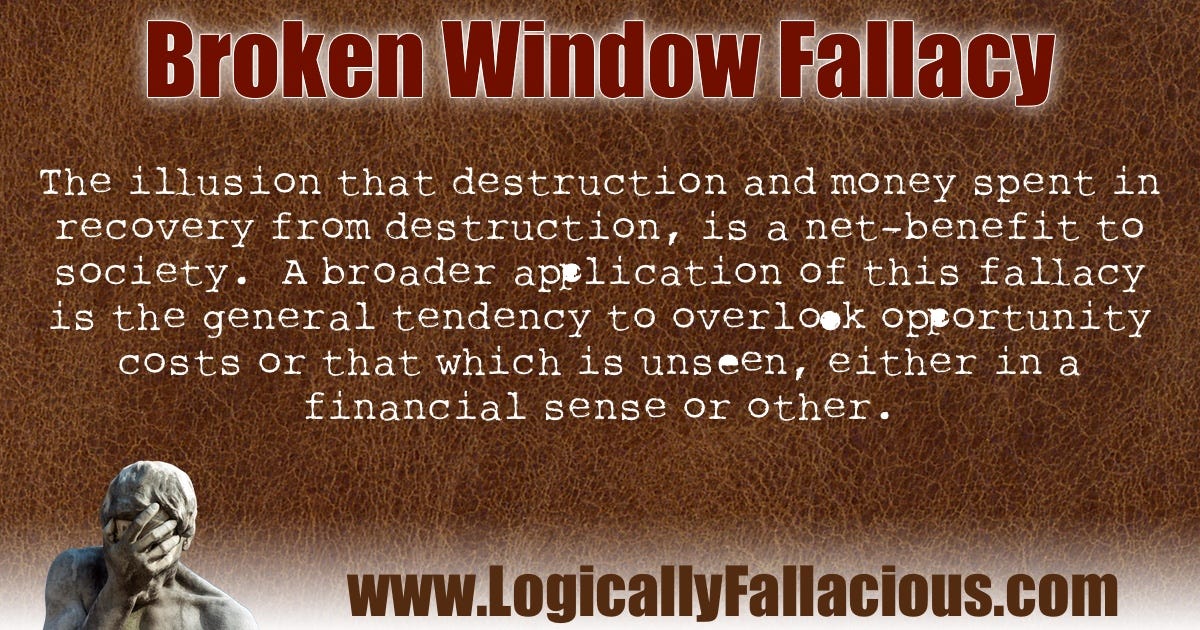

The argument is correct — and deeply misleading. It’s a technophile’s variant on the classic Broken Window Fallacy. Yes, if a child shatters your window, you’ll probably replace it with a shiny, new upgrade. But that hardly shows that the vandal did you a favor. There’s a reason you hadn’t already upgraded: You had better things to do with your resources than maximize window quality.

Innovative resources are, like everything else, finite. So if you’re blessed with abundant cheap labor, you won’t try as hard to figure out how to save labor. Nor should you. Instead, you should rack your brain to figure out how to save precious resources that are actually in scarce supply.

When I was an undergrad, a Ph.D. student instructor told my intermediate micro class that the U.S. should double the gas tax every year. That way, he gushed, all the brightest minds would desperately search for a replacement. A fine forecast, but his idea was idiotic nonetheless. If you’re blessed with cheap, abundant energy, you should enjoy it — not tax it into oblivion to speed low-value innovation.

The same holds for “cheap labor” — foreign and domestic. Yes, if government strangles abundant labor supply, business will look for higher-tech alternatives. But that means they’ll fritter away precious innovative resources to “solve” a problem that is already well-solved. Which deprives us of the brainpower we need to solve our inescapably serious problems. Such as death.

Bottom line: Market prices don’t just tell us how to use existing technology. Market prices also tell us what as-yet-undiscovered technologies we should try to bring into existence. If we really cared about maximizing overall progress, we wouldn’t be keeping out low-skilled migrants. We’d welcome the world, showering our scientific and business elites with nannies, maids, cooks, drivers, and gardeners. Yes, keep the talent happy, so it can spend its time and bandwidth making all of our futures brighter.

Thanks. This is a good argument. I disagree with open borders for non economic reasons, but I appreciate your clarifying this error in my thinking.

Bryan is quite correct in all of his argument until the end.

Then when he suggests we should “welcome the world, showering our scientific and business elites with nannies, maids, cooks, drivers, and gardeners”, he is specifically going back to and ignoring the thing that “Critics of low-skilled immigration usually lament”: “their effect on low-skilled natives.”

So his statement is technically accurate - what we should do if we *solely* care about maximizing technological innovation, *if* we get to hold everything else constant - but politically even more tone deaf then he usually is on open borders.

Because in the real world, populist political forces would almost surely *not* hold everything else constant, and we would be more likely to end up with even worse government that was more anti-growth, and most probably end up with less innovation, not more.

Which means ironically that with his last argument, imo Bryan himself is guilty of a variant (not exact, but a close cousin) of the Broken Window Fallacy.