I Know a Guy Who Knows a Guy

Or, the economics of Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon.

Externalities trouble the sleep of the economics profession. If a total stranger’s actions hurt me, what reason does he have to feel my pain? If a total stranger’s actions help me, what reason does he have to feel my joy?

Sure, your family, friends, and business associates have an incentive to take your interests into account. After all, you know each other. There’s repeated interaction, so what comes around, goes around. If your boss treats your worse, he’ll either need to give you a compensatory raise, or accept a higher turnover rate. If a merchant treats you better, you’ll either have to pay a higher price or accept extra congestion.

When you deal with total strangers, however, none of this logic applies. A total stranger can scratch your car, shrug, and drive off. He can befoul the air you breathe. He can loudly swear in front of your kids. However much you sputter, you’re not going to do much about it. You probably won’t even know the name of whoever brought these negative externalities down upon you. The same goes for positive externalities. A total stranger could go out of his way to pick up litter in your vicinity, but why should he bother?

Sure, there are numerous responses to these fears, starting with: “Most people aren’t totally selfish.” One response I’ve rarely heard, though, is simply we hardly ever interact with total strangers. In real life, people we think of as “strangers” are usually, on reflection, socially connected to us. If you don’t know him, you know someone who knows him, or know someone who knows someone who knows him.

Suppose you’re at the local mall. You’ve never met 99.9% of the other shoppers. But you’re all customers of the same shopping center. Each of you “knows a guy who knows a guy” - or to be more precise, each of you knows a business who knows each of the other customers. As a result, the mall managers have a clear incentive to manage the mutual externalities of all the folks at the mall. Though you have no direct relationship with the other customers, the mall managers have direct relationships with each of you. If you talk loud or smell bad, it’s bad for the other customers, which is bad for the mall, which is bad for business: “Sir, I’m afraid I’m going to have to ask you to leave.”

The same goes in an apartment complex. You might never even see your immediate neighbors. The apartment owner, however, does business with each of you. So if you bother your neighbors with loud music, you are indirectly bothering the owner. Which gives him a clear incentive to involve himself. Maybe he’ll ask you to turn down your music. Maybe he’ll plan ahead and make the walls sound-proof. Whatever the owner does, he has a strong reason to take all of his future tenants’ interests into account. After all, if he fails to provide good quality of life, he’ll have to cut his rents to fill his units.

The logic is clearest of all on the job. You don’t know most of your fellow workers. But your immediate boss knows you, he knows his boss, and so on all the way to the top. There is no “I” in team, and there are no total strangers on the job. If workers make each other unhappy - or even fail to make each other happy - this is bad for business. Either the boss will have to pay higher wages, or accept higher turnover with all its attendant ills. As a result, the hierarchy has a clear incentive to manage externalities thoughtfully.

You could object, “This doesn’t fit my experience. I never had a boss who minimized negative externalities or maximized positive externalities on the job.” But this objection misses the basic economic logic. While non-economists may think of externalities as injustices to eliminate, the textbook focuses rather on conflicts to manage thoughtfully. And as Coase taught us, “managing conflicts thoughtfully” is incompatible with minimizing negative externalities and maximizing positive externalities. Why? Because many negative externalities cost too much to eliminate, and many positive externalities cost too much to deliver. And yes, in the real world one man’s negative externality is another man’s positive externality. The prudent response is to figure out who’s willing to pay more to get their way.

For example, a profit-maximizing employer under laissez-faire would limit sexual harassment, but wouldn’t make its utter elimination his top priority. Instead, he would balance the dislike of unwanted attention against the like of wanted attention. He would balance the dislike of hearing what you don’t want to hear against the like of saying what you want to say. Just as any intro textbook written by anyone who knew his Coase would recommend.

“I know a guy who knows a guy.” This line doesn’t just help us understand why externalities are more livable than you’d think. The line also shows us how to make our own lives more livable. Instead of griping about the callous way that total strangers treat you, why not search for the agents who subtly connect you? Maybe you’ll wrack your brain and discover that no such agents exist. More likely, however, you’ll soon realize that you and the “total strangers” are already part of a shared social network that is already prepared to resolve your differences.

It has been interesting (in a very bad way) to observe in the last three years how one particular externality that we can all cause, the possibility of passing on a virus, has gone from something we felt did not justify the cost to reduce very significantly, to something we seem willing to incur incredibly high costs to reduce.

How much of our understanding of the cost and benefits of externalities is shaped by cultural and social factors, availability bias etc? Quite a lot it seems.

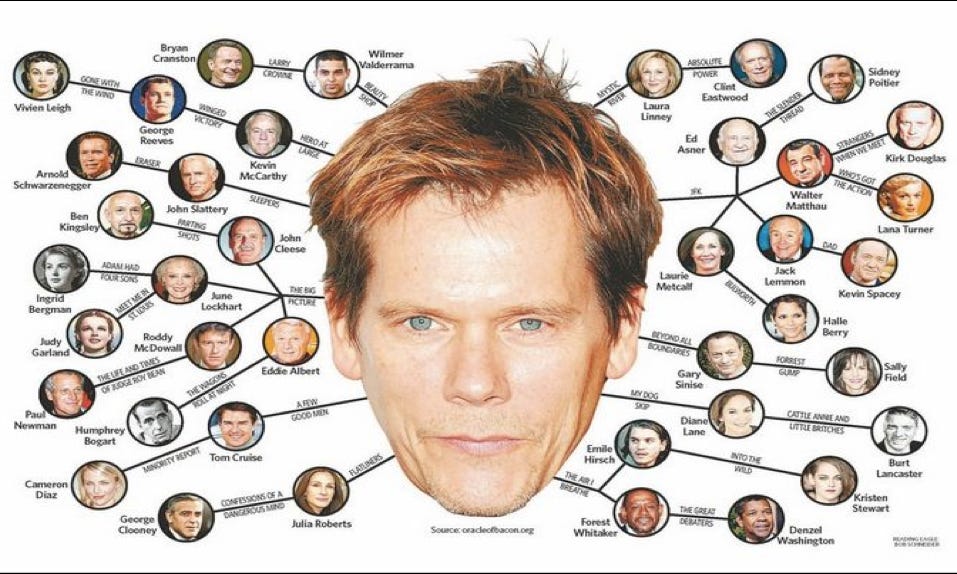

Also: now I know Cameron Diaz was in Minority Report!

As an employer I tell my people to give and get their attention somewhere else than the workplace. It works fine. If two employees have coupled off that's also fine, but they're here to work not to feel each other up all day. It's vital, with employees, children, or colleagues, to set boundaries. Morality, being the predecessor of a written code of law that avoids internal conflict in a community, includes boundaries in its word cloud. Thus I consider that small-scale interactions such as you have described are more part of the give-and-take normal in a peaceful society. To get my notice as an externality it would have to be quite a bit bigger and involve someone a lot closer than my cousin in Australia's neighbor's chiropodist.