Dementia, Antihistamines, and Cost-Benefit Analysis

I’ve had severe allergies for as long as I can remember. Until my early-20s, I assumed I just had to live with them. Then my doctor at Princeton recommended Benadryl, which virtually cured my problem. Since then, I’ve taken antihistamines at the slightest sign of a runny nose. I’ve consumed at least 25 mg per day for over two decades. When I started hearing “Antihistamines increase dementia risk,” I was not pleased.

Despite my generic skepticism of the media’s coverage of science, I realized that if anyone was at risk, it was me. Now that I’ve finished the penultimate version of The Case Against Education, I decided to track down the original research. Here’s the full text of Gray et al.’s “Cumulative Use of Strong Anticholinergics and Incident Dementia” (JAMA Internal Medicine, 2015), and here’s the technical appendix. (All notes omitted).

Where the data come from:

This population-based prospective cohort study was conducted within

Group Health (GH), an integrated health-care delivery system in the

northwest US. Participants were from the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT)

study and details about study procedures have been detailed elsewhere.

Briefly, study participants aged 65 years and older were randomly

sampled from Seattle-area GH members. Participants with dementia were

excluded… Participants were assessed at study entry and

returned biennially to evaluate cognitive function and collect

demographic characteristics, medical history, health behaviors and

health status. The current study sample was limited to participants with

at least 10 years of GH health plan enrollment prior to study entry to

permit sufficient and equal ascertainment of cumulative anticholinergic

exposure… Of the 4,724 participants enrolled in ACT, 3,434 were eligible

for the current study…

Measuring dementia:

The Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI) was used to screen

for dementia at study entry and each biennial study visit.

CASI scores range from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating better

cognitive performance. Participants with CASI scores of 85 or less

(sensitivity 96.5%; specificity 92%)

underwent a standardized dementia diagnostic evaluation, including a

physical and neurological examination by a study neurologist,

geriatrician or internist, and a battery of neuropsychological testing.

Measuring drug use:

Medication use was ascertained from GH

computerized pharmacy dispensing data that included drug name, strength,

route of administration, date dispensed, and amount dispensed for each

drug. Anticholinergic use was defined as those medications deemed to

have strong anticholinergic activity as per consensus by an expert panel

of health care professionals…To create our

exposure measures, we first calculated the total medication dose for

each prescription fill by multiplying the tablet strength by the number

of tablets dispensed. This product was then converted to a standardized

daily dose (SDD) by dividing by the minimum effective dose per day

recommended for use in older adults according to a well-respected

geriatric pharmacy reference (eTable 1). For each participant, we summed the SDD for all anticholinergic

pharmacy fills during the exposure period to create a cumulative total

standardized daily dose (TSDD).

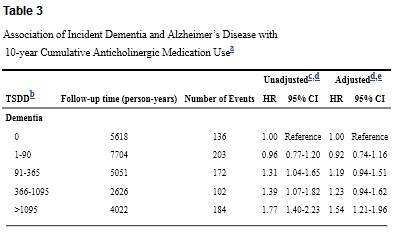

Here are the results for all-cause dementia, both raw and adjusted for cohort, age, sex, education, BMI, smoking, exercise, self-rated health, and a bunch of specific ailments. HR is the risk ratio; 1.31 indicates 31% elevated risk.

Overall, this is an impressive study. Yes, it only looks at seniors. Yes, there’s potential reverse causation. Yes, there are wide confidence intervals. But as far as observational studies go, it would be hard to do much better. And at least for me, the results are scary. Daily use for 3 out of 10 years puts you in the top category, with dementia risk elevated by over 50%.

As an economist as well as a Gigerenzer fan, I’m know risk ratios are a poor guide to action. I’d gladly increase my risk of being struck by lightning by 54% in exchange for one good ice cream cone. Why? Because the normal risk of being struck by lightning is minuscule. For dementia, sadly, the opposite is true. Almost one-quarter of seniors in the study ended up with dementia. But what about those big confidence intervals? They show the

danger could be much lower or much higher, but that’s all. The high

point estimates remain a reasonable guide to action.

Many will respond, “So you’re pretty likely to get dementia either way,” but that’s terrible economic reasoning. Raising the risk of losing your mind by roughly 10 percentage-points is awful – regardless of whether you’re raising the risk from 0% to 10%, 20% to 30%, or 90% to 100%. See the Allais Paradox if you’re still in doubt.

My two main initial doubts about the study:

1. While the authors brag about their dose-response function, it’s none too neat. The point estimates for low doses are negative. The point estimates for moderate doses – 95-1095 doses – are almost flat. Only the top category features a big jump. And what’s the point of these discrete categories, anyway? Why not log dosage (or dosage +1 so non-users remain in the sample), or include linear and quadratic terms? (If anyone gets the data and runs these regressions, I’ll gladly blog the results).

2. While this seems a high-quality study, publication bias is endemic; dramatic results sell. So I suspect the true effects are markedly smaller than the reported coefficients.

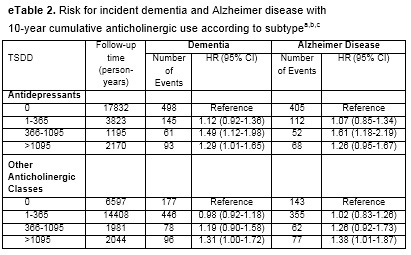

Reviewing the technical appendices added to my doubts. Splitting the results between antidepressants and all other anticholinigerics matters greatly. (Table reformatted for readability; all results adjusted for aforementioned controls).

With this partition, moderate use of antidepressants looks less dangerous than heavy use. And other anticholinergics just look notably safer than in the baseline results.

Patterns in eTable 5, which sub-divides results for past, recent, and continuous users, are also odd. You’d expect continuous users to do the worst, but they actually do the best. Confidence intervals are large, but still.

Given everything I’ve learned, what will I do? I definitely won’t return to my early decades of hellish allergies. Popular write-ups advise switching to second-generation drugs like Claritin. But, Claritin seems ineffective for me – and the research I’ve seen leaves its side effects unassessed.

Instead of doing anything drastic, I’m applying marginal thinking. Since serious effects aren’t evident at high doses, I’m cutting back – testing how low I can go without distress. Now that early spring is over, I’m almost asymptomatic without using any antihistamines at all. My tentative plan, then, is to limit my use to the worst allergy weeks of the year. If you’ve got better advice, please share.

P.S. Shouldn’t a Szaszian deny the reality of dementia? No. As I’ve often explained, Szaszianism is best interpreted as an empirical claim. The best way to delimit its applicability is measuring responsiveness to incentives:

The distinction between constraints and

preferences suggests an illuminating test for ambiguous cases: Can

we change a person’s behavior purely by changing his incentives?

If we can, it follows that the person was able to act differently all

along, but preferred not to; his condition is a matter of preference,

not constraint. I will refer to this as the ‘Gun-to-the-Head Test’. If

suddenly pointing a gun at alcoholics induces them to stop drinking,

then evidently sober behavior was in their choice set all along.

Conversely, if a gun-to-the-head fails to change a person’s behavior,

it is highly likely (though not necessarily true) that you are literally

asking the impossible.

Like mental retardation, and unlike alcoholism and symptoms of personality disorder, dementia seems highly unresponsive to incentives. So while I have zero worry of suddenly becoming an alcoholic, dementia really could happen to me. And I really don’t want it to…

The post appeared first on Econlib.