Convenience vs. Social Desirability Bias

Convenience has a massive effect on your behavior. You rarely shop in your favorite store, eat in your favorite restaurant, or visit your favorite place. Why not? Because doing so is typically inconvenient. They’re too far away, or not open at the right hours, so you settle for second-best or third-best or tenth-best. You usually don’t switch your cell phone company, your streaming service, or your credit card just because a better option comes along. Why not? Because switching is not convenient. Students even pass up financial aid because they don’t feel like filling out the paperwork. Why not? You guessed it: Because paperwork is inconvenient.

In politics, however, almost no one talks about convenience. When governments mandate extra privacy or safety or consumer protection, crowds cheer and pundits sing. From now on, you’ll be clicking a few extra boxes a day. From now on, you’ll have to stand ten feet away from the next person at the pharmacy. From now on, you’ll have to sign your name and initials twenty times on a mortgage contract. Privately, almost everyone thinks each of these is a pain in the neck. Yet almost no one goes on TV and self-righteously objects, “These high-minded ideals are going to be awfully inconvenient.”

What’s going on? The Panglossian explanation is that there’s almost no political resistance to the inconvenience of extra privacy, safety, and consumer protection because these benefits are clearly worth the loss of convenience. Yet that’s hard to reconcile with the enormous effect of convenience on our actual behavior. Furthermore, we routinely complain about inconvenience one-on-one, or with trusted friends. When people are speaking off the record, I’ve heard at least a hundred times as many complaints about inconvenience as I’ve heard about lack of privacy, safety, or consumer protection.

How can we explain this chasm between daily life and political rhetoric? By appealing to Social Desirability Bias. Quick version: When the truth sounds bad, people respond with lip service – especially where there’s a sizable audience. People occasionally voice ugly truths one-on-one, or with trusted friends. Normally, however, they sugarcoat. If “what sounds good” conflicts with “what works well,” we usually respond with hypocrisy; we say what sounds good, then do what works well.

In politics, alas, words rule. From the viewpoint of any individual voter, elections are surveys. As a result, demagogues run the world. They gain power by swearing fealty to lofty ideals, not weighing costs and benefits. And when lofty ideals imply serious inconvenience – as they sadly do – the demagogues impose serious inconvenience.

Why doesn’t a rival politician gain power by promising to make convenience great again? Because “convenience” sounds petty and ignoble. People love convenience. They happily sacrifice other values for convenience. But they don’t want to acknowledge this fact – or affiliate with those who do.

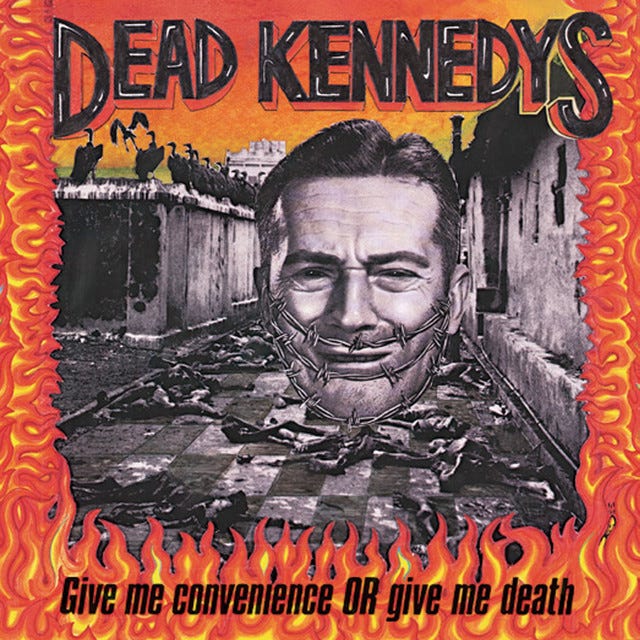

My favorite Dead Kennedys album is called “Give Me Convenience or Give Me Death.” The music is great, but the message is not. The band heaps scorn on our wicked First World society for placing immense weight on the superficial consumerist value of convenience.

The reality, however, is more complicated. Yes, we long for a convenient world. A little inconvenience can ruin your entire day. No one, however, will ever go to the barricades for convenience. In fact, we’re ashamed to admit how much convenience matters for our quality of life. The market mercifully sells us the convenience we want without judging us. Government, in contrast, takes us at our word – and robs us of precious convenience bit by bit, day by day.

The post appeared first on Econlib.

How might a rival politician campaign on MCGA by another name so as not to make it sound ignoble and petty? Might he say, "I want us all to have good lives, to make things easier for people to achieve their goals, enjoy their daily lives. Not put up barriers," etc. (That doesn't sound good off the cuff here. My brain if a little foggy this morning.) But I'm asking what might such a message sound like?

I imagine that if you owned the thing upfront and tied it to morality, you could sell it. It would take a talented and charismatic politician who understood the connection clearly and who was able to articulate it consistently and in different ways among different people at any event, planned or spontaneous, big or small. But it would start to get into the consciousness of enough of the people, wouldn't it?

It might be a market-generated phenomenon (and a cultural one) as much as a political policy shift, but I see the rise of convenience EVERYWHERE. I think we've barely begun to confront the implications for our freedom, and when you combine 'convenience' with identity authentication and 2FA and bureaucracy and rules and hiring quotas and secret (universally understood, but never stated) speech codes and all the rest - and then you add the constant, frenetic grasping for STATUS - you quickly approach a shallow and managed world, without risk or magic. Such a world would make some people very happy.

https://jmpolemic.substack.com/p/job-search-part-6