Anarcho-Capitalism: Reply to Coelho

Last December, I told you I’d respond to this guest post on anarcho-capitalism by Rodrigo Coelho “in a week or two.” My apologies to both Rodrigo and all my readers for the long delay, but here you go. He’s in blockquotes; I’m not.

I’ve read a lot of anarcho-capitalist literature over the years… But I was never really convinced.

First, a common argument you make which seems pretty convincing at first is that there are more private security guards than police in the US (and maybe a few other countries as well). You also mention gated communities and private commercial arbitration as prime examples of the market providing services that are typically thought of as the sole province of government.

But my main objection to that is simply that all of those exist within a framework of laws provided by the government. It’s not at all clear to me that those would work just as well without a government providing a robust rule of law that applies to everyone in society.

All reasonable points. These arguments are targeted at people who can’t even imagine private supply of police, courts, and so on. They’re only intended to show that private supply is possible, not demonstrate that private supply is superior.

To further emphasize this point, if we look at history it’s clear that the most successful nations are the ones that adopted free-market principles to the largest extent and that the closer we get to laissez-faire the better the outcomes, in terms of freedom and prosperity, seem to be.

But all examples of tremendously successful and relatively laissez-faire economies, whether historical (late 19th century America and Britain) or contemporary (Switzerland, Singapore, Hong Kong, and a few other city-states) have existed under a system of laws provided by the government.By contrast, stateless societies have been the norm for large chunks of human history. Various anarcho-capitalists have cited medieval Iceland and Ireland as examples of societies that had elements of anarcho-capitalism. I’m honestly not educated enough about these to judge properly, but both lasted for multiple centuries (according to Murray Rothbard in For a New Liberty, the “libertarian” society of Ireland even lasted for a thousand years) and neither seems to have led to anything remotely close to the industrial revolution in terms of growth and innovation.

True. But the last three centuries have been special in many ways. Science and technology advanced rapidly. Religion declined. Nationalism exploded. “Systems of law provided by government” have existed off and on for thousands of years. So why give “systems of law provided by government” the credit when amazing things finally happen?

There seems to have been something unique about the British (and later, American) political tradition, when it comes to the rule of law and the protection of property rights, which took centuries to develop (starting from at least the Magna Carta) and played a crucial role in enabling the industrial revolution and the unprecedented increases in freedom, prosperity, innovation, and overall human flourishing of the 19th century.

Isn’t this “centuries to develop” point suspicious? The Magna Carta was signed in 1215, but the “unprecedented increases” don’t start for five or maybe six centuries. Sure, you could say that “The Magna Carta was only the beginning,” but the political improvement was gradual, and there is little sign of “unprecedented increases” in anything on your list for multiple centuries.

Given the examples I mentioned of successful nations with relatively free-market economies backed by a strong rule of law provided by the government, when we compare them to the mediocre stateless societies it seems reasonable to conclude that a good legal system is a precondition of free markets, not the other way around.

A precondition for free markets, or a precondition for “unprecedented increases”? If the latter, why not give primary credit to modern science and technology?

And even if you’re right that “strong rule of law provided by the government” is a precondition for “unprecedented increases” to start, that hardly shows that free-markets can’t eventually take over. Once a government court system and legal tradition is established, for example, private arbitration can and does emerge to remedy their obvious shortcomings. And even replace the preceding system.

And, to clarify, I’m willing to fully concede that the standard Hobbesian objection to anarchism might not be true in all cases. It’s entirely possible that whatever social arrangement they had in medieval Iceland or Ireland, it was in fact close to anarcho-capitalism in some respects and it didn’t lead to constant gang warfare. And also that if we were to repeat that kind of system today it might not necessarily lead to chaos in the streets.

Fair enough.

I just think that, by the various standards I mentioned (including individual freedom), this kind of system seems to fall short of free-market economies with a legal system provided by the government. It’s not at all clear that, even if those security firms don’t go to war with each other to resolve disputes, whatever compromise they would come up with would respect individual freedom better than even the status quo today in most Western mixed economies.

If you just picture anarcho-capitalism suddenly replacing the status quo, I agree that it’s “not at all clear.” But if you picture anarcho-capitalism emerging piecemeal, taking over traditional functions of government one by one, it is fairly clear. Especially once you acknowledge how deeply unlibertarian Western mixed economies really are.

To his credit, David Friedman acknowledges this eventuality in The Machinery of Freedom, when he recognizes that an anarcho-capitalist society might be far from libertarian/classical liberal in terms of rights-protection.

“Might be”? Yes, but he also offers strong reasons to expect anarcho-capitalism to be much more libertarian than the status quo. People just care a lot more about self-protection than they do about imposing their philosophy on strangers.

Another, more obvious, objection I have to anarcho-capitalism is that if the “free market” (which, without a government, we might as well call the state of nature) leads to an efficient provision of the government services involving the use of force, then how did governments even come about in the first place?

A great question that I think I answered credibly here. Quick version: “[S]cale economies are weak now, but things used to be very different. States emerged at a time when markets were too small to sustain more firms. Over time, the economic rationale for monopoly has grown weaker and weaker. Competition could work now, if you gave it a chance. But the state doesn’t care about economic rationales. As long as it can credibly threaten to put new entrants in jail, its monopoly endures.”

Finally, there are two sort of big deals in life that I haven’t seen any anarcho-capitalist address convincingly: children and nukes.

Under anarchy, what happens when a child abuser has a kid? Sure, you could point to the many flaws in the government system, but at least there’s a relatively uniform system of laws in place that apply to children. Under anarchy, children presumably wouldn't be customers of any rights-protection agency.

Libertarians’ standard response to a long list of social ills is to appeal to philanthropy. “Protecting defenseless kids from child abuse” seems like an especially easy cause to raise money for. And unlike, say, global poverty, a cheap problem to remedy because child abuse is rare.

Similarly, you could point out that, under government, absolute maniacs like Kim Jong Un and Vladimir Putin have access to nuclear weapons. But still, the number of people in the world in possession of nuclear weapons is relatively small and they’ve only been used in one war in the span of almost a century. There are far worse possible outcomes than that.

What happens under anarchy? Could anyone just own a nuke? While developing a nuclear weapon is obviously no walk in the park, it seems reasonable to assume that under anarchy there would probably be more nukes than today given the billions of people on Earth who would suddenly be free to develop and own them. Even if one buys the idea that nuclear proliferation leads to more deterrence at the international level, I think it’s definitely not crazy to have more than a few doubts at the individual level. Anyone with a nuke could basically declare himself a tyrant.

Even when you have the resources of an entire country — and lots of past experience to draw on — building a nuke is very hard. So the idea that private individuals would build nukes for themselves seems fanciful to me.

How would an anarcho-capitalist system handle the problem if it arose? Probably by preemptively arresting anyone trying to build a nuke. Absolutist libertarians might object, but they’d be a tiny minority even in an anarcho-capitalist society.

On a related note, a problem you’ve acknowledged in The Economics of Non-State Legal Systems (parts 1, 2, and 3) is the sort of catch-22 that the more economies of scale for the production of security would exist under anarchy the more effective that society would be at protecting itself from foreign threats, but also the greater a risk of cartelization there would be between the few security firms that could thus consolidate back into a government (which might or might not be worse than those we have today). And vice versa.

And, sure, you’re absolutely correct when you point out that “National defense is, strangely, only a public good on the assumption that some military forces are a public bad.” But if an anarcho-capitalist society would require the entire world to eliminate its military forces in order to be able to protect itself from foreign threats… Well, you see the problem.

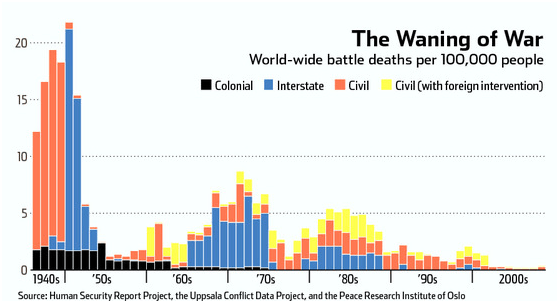

My ultimate view is that economies of scale in defense are modest, so anarcho-capitalist societies would indeed be bad at protecting themselves from determined foreign threats. But the full pacification of the world is, despite recent blips, well underway. Humanity has made enormous and unprecedented progress in that direction since 1945. If anarcho-capitalism ever comes, the world will probably already have been at peace for a long time.

Appreciate the response. Better late than never! (just please correct my name in the title)

I think you’re right that I probably overstated the uniqueness and role of the British legal system in the lead-up to the Industrial Revolution. But I’d still maintain that it established the foundations. More of a necessary than sufficient condition. Roman law likely met those standards as well.

Otherwise, all I can add is that I’d definitely like to see the experiment of anarcho-capitalism on a small scale (through charter cities, seasteading, and the like).

“a good legal system is a precondition of free markets, not the other way around.”

I agree, but how is this a criticism of anarchocapitalism? If a good (I read that as reasonably effective, transparent, understandable, and adaptable) legal system is so beneficial, that is what people will want to buy, and that is what suppliers will sell. Just because people are able to innovate, that doesn’t mean that there are not powerful incentive for standardization.